Croxley Green School - 1875-1894 Mixed all Ages

Referred to as Croxley Green National School, the first school to be built for the village children was opened on Monday 4th January 1875 and 71 children were admitted with ages ranging from 5 to13 years. Miss Harriette Lawrence was appointed Headmistress. It would appear that as soon as the child reached 13 years old their education was completed. However, some children were withdrawn sooner for family reasons. The Headteacher maintained a weekly logbook which provided a permanent record of principal events affecting scholastic activities.

The following year (1876) Miss Aricie Clarke replaced Miss Harriette Lawrence/Lucas. Miss Clarke was born in Cambridge in 1851 and attended the Norwich Diocesan Training Institution for School Mistresses.

The following year (1876) Miss Aricie Clarke replaced Miss Harriette Lawrence/Lucas. Miss Clarke was born in Cambridge in 1851 and attended the Norwich Diocesan Training Institution for School Mistresses.

The school was to become known as Yorke Road School as Garden Road was changed to Yorke Road after Charles F. Yorke, a local resident who became Chairman of the Rickmansworth Urban District Council. It was decided to designate the school as a church school with the running and maintenance chiefly the responsibility of the Church with grants available from both the Education Authorities and by request from the Church Charity Commissioners.

All schools were subject to regular inspection by Government Inspectors. An HMI (His /Her Majesty’s Inspector) would visit the school and record his findings on a special form 84E and the report would be submitted to The Secretary, Board of Education, Whitehall, London. Many of these reports were copied and recorded in the school logbook. Financial grants were largely dependent upon the findings evidenced in the report.

The work of the school was closely monitored by a group of ‘managers’ including the vicar and leading members of All Saints Church, Dickinson’s paper mill, together with prominent personages from the village. In many ways these people were the equivalent of today’s school governors. The school was also monitored by the St Albans Diocesan. They too made regular visits to check on the school’s progress and in particular the children were examined with regard to their knowledge of the Bible. The vicar also paid regular visits and conducted morning assembly with prayers and on alternate days the children would assemble in the church for a service.

The logbook records that during the school’s first year the village children celebrated May Day. This was to become an annual tradition. The girls were given time off from school to collect May blossom in order to make garlands. The pupils paraded to The Green and danced in traditional style around a maypole.

All schools were subject to regular inspection by Government Inspectors. An HMI (His /Her Majesty’s Inspector) would visit the school and record his findings on a special form 84E and the report would be submitted to The Secretary, Board of Education, Whitehall, London. Many of these reports were copied and recorded in the school logbook. Financial grants were largely dependent upon the findings evidenced in the report.

The work of the school was closely monitored by a group of ‘managers’ including the vicar and leading members of All Saints Church, Dickinson’s paper mill, together with prominent personages from the village. In many ways these people were the equivalent of today’s school governors. The school was also monitored by the St Albans Diocesan. They too made regular visits to check on the school’s progress and in particular the children were examined with regard to their knowledge of the Bible. The vicar also paid regular visits and conducted morning assembly with prayers and on alternate days the children would assemble in the church for a service.

The logbook records that during the school’s first year the village children celebrated May Day. This was to become an annual tradition. The girls were given time off from school to collect May blossom in order to make garlands. The pupils paraded to The Green and danced in traditional style around a maypole.

The annual summer holiday break was known as ‘Harvest Holiday.’ It began at the end of July each year to coincide especially with the farms’ summer harvesting time. During this time, even very young children were expected to help their parents on the land. They were also encouraged to work as paid help on nearby farms, thereby contributing to the family income. Even though this type of activity no longer happens, school children continue to be allocated the summer holiday at this time. The religious celebration of Harvest Festival was celebrated at All Saints Church. Children brought offerings of fruit and flowers and assisted in decorating the church. A special day’s holiday was also arranged in celebration of Guy Fawkes Day.

Occasionally, children absent from school were to be seen working at gathering acorns (food for pigs), picking elderberries and blackberries to make cordials or wine and ‘stone picking.’ The heavy ploughing brought large stones to the surface which had to be removed or picked out by hand thereby enabling crops to be sown. After the harvest children worked in the fields seeking and collecting any remaining grain left behind. This exercise was known as gleaning , and when collected the grain could be taken to the windmill to be ground into flour for household use.

Attendance at school became compulsory; the logbook states in 1885 that a number of parents were fined for failing to send their children to school. This was intended to ensure that there was no unnecessary interruption to their education. However, it is also logged that when the school had full attendance, they were given a day off!

Many illnesses were experienced, with annual outbreaks of mumps, diphtheria, ringworm, measles, scarlet fever, influenza and bronchitis. Some logbooks record incidents of child deaths caused by these illnesses.

Pupils came from the outlying areas around Croxley Green including Redheath. Many walked to school. This meant negotiating long, rough country lanes which often had no hard surface. Severe weather conditions often prevented infants from attending, particularly during winter months, sometimes from the end of November to early February.

Early records indicate that the children attending Yorke Road School were very fortunate in the high degree of pastoral care shown them as well as the high standard of education they received. Children moved upwards through the school by virtue of improved ability and not necessarily because of age. The pupils were tested in ‘Standards.’ Standard 1 commenced at seven years of age and by age thirteen they were expected to have achieved Standard 7. The range of subjects taught included the normal 3 R’s (this was a term used for reading, writing and arithmetic) as well as marching and drill movements. Having eventually reached a high standard, some pupils became paid monitors and taught the younger children. It is logged that one particular female monitor had 60 children in her care!

When the young boys first started school, Miss Aricie Clarke, Headteacher, introduced them to singing and any boy whose voice showed potential was encouraged to join the church choir.

A favourite venue for the Methodist Chapel Sunday School (sometimes referred to as Primitive Methodist) annual ‘treat’ was Bricket Wood where a popular fair was held on a permanent site. Children who attended this chapel were given a day’s or half day’s holiday from Yorke Road School so that they could attend and those pupils remaining just had time off.

Children were usually seated at desks in rows facing the front, or the very young were given benches to sit on, especially in times of over-crowding. Writing materials could be very scarce and each child was given a small board made of slate and a piece of chalk or possibly a slate pencil to use for their writing and sums. They progressed to desks and paper and pencils as and when these items could be afforded.

The desks had ‘wells’ for ink and writing was achieved using a pen with a metal nib. The desktops lifted up for storing books and pencils used by the pupils. Each pupil sat at the same desk unless moved by the teacher for a specific reason. When the school became very overcrowded the very young were provided with forms to sit on so that they could all be accommodated together!! Heating was by a cast iron stove in each class room.

Games were an important part of the children’s break from school work. Skipping ropes for girls were very popular and if a large one was available and two strong ‘turners’ many children could skip together in the centre of the rope. Wooden spinning tops were also very popular, and these were painted with coloured chalk on top to make fascinating effects when whipped with a stick that had a fine piece of leather attached. Marbles were a favourite with boys and could be ‘flicked’ against a wall or a board. During the autumn time, seeking out conkers (horse chestnut fruits) of the most desirable size and shape could be a serious task, as to win a conker competition was indeed the ultimate goal for a determined school boy. A ‘secret’ but not necessarily an honest ruse was to bake the conker first. After threading it on to a long piece of strong string the boys attempted to smash each other’s conkers by taking swipes at them- hopefully avoiding rapping the opponent’s hand!

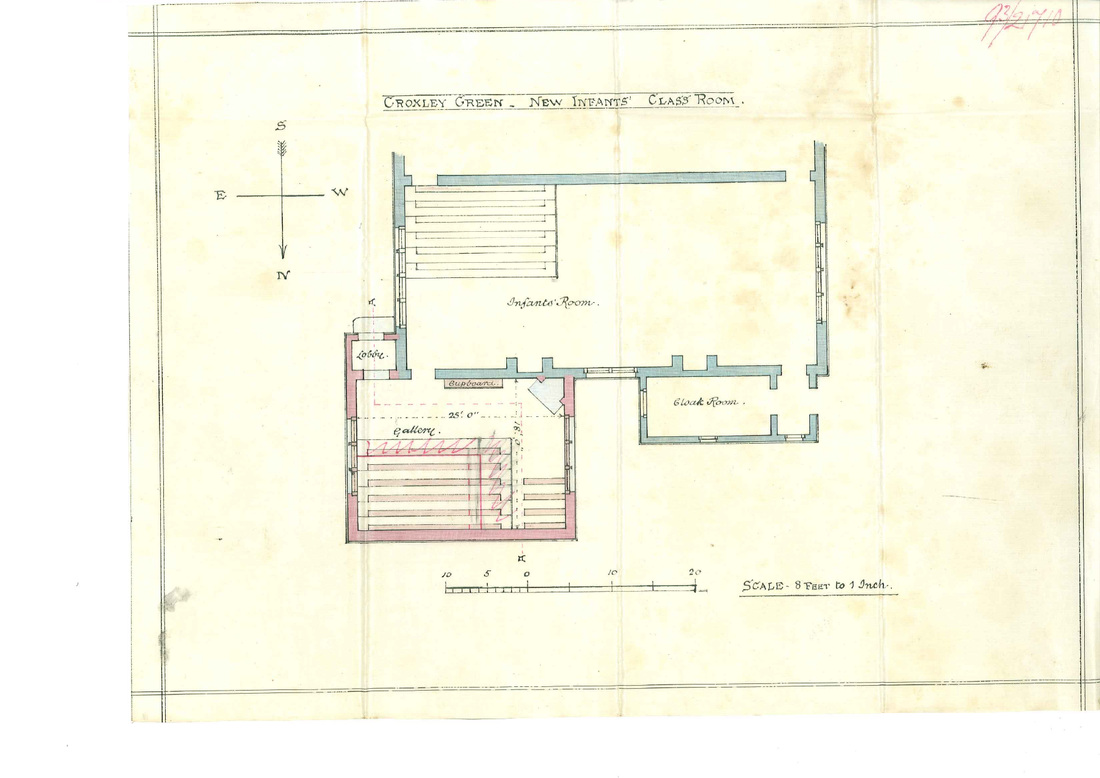

The ever increasing population of the village, largely due to the continuing growth of John Dickinson’s Mill, inevitably increased the number of school children during the early 1880’s.This number reached 156 and Her Majesty’s School Inspector became concerned that the school accommodation was inadequate. Accordingly, the main room 50’x 22’ was partitioned. Another room 25’x 18’ was identified for use by the ‘babies’ or infants. In 1888 a letter was sent to the Board of Education requesting that this situation should be remedied and plans were agreed for an extension. A specification for tender was made to local builders and by 1889 enlargements to the school were completed and the number of pupils increased to 235. The infants were now taught by the newly appointed Headmistress, Miss Ellen Martha Walter. Miss Annie Denham was Assistant Mistress and Florence Brown (a fourth standard girl) was “Monitress”.

It would appear that many teachers were not fully trained when they started but following their teaching practice and examinations they would become qualified.

Miss Clarke continued as Headmistress to the older boys and girls aged seven to leaving age.

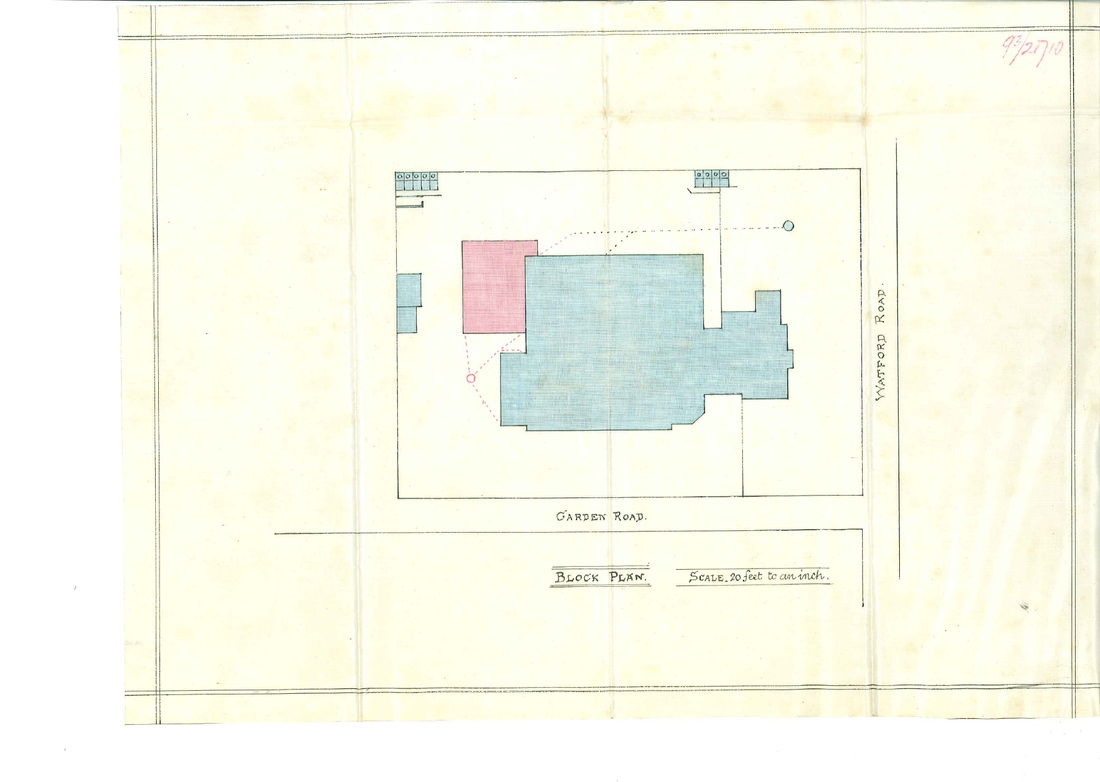

As more and more housing was erected in the village, the school accommodation for the children became hopelessly inadequate once more. School fees were eventually abolished. In the early 1890’s parents had been expected to pay an annual fee of about 12s 0d per pupil (twelve shillings = approx. 60p) but this could be varied. In June 1893, the logbook shows that ‘The children are not making much progress as the classes are so large. When the children write on paper they have to stand and sit alternately.’ It was decided, following an extensive building programme in 1894 that changes would have to be made. This gave rise to the infants being separated from both the older boys and older girls over seven years of age. The infants, who had seen several changes of Headmistresses since 1889, were currently under Miss Emily Haigh. Miss Aricie Clarke became Headmistress of the older girls to whom were designated the larger rooms of the original school and a separate playground. The older boys, of seven and over, were now moved out to the newly built school in the Watford Road. This was just a short distance away and Mr. Alfred Walter Stratton-Hanes was Headmaster.

Occasionally, children absent from school were to be seen working at gathering acorns (food for pigs), picking elderberries and blackberries to make cordials or wine and ‘stone picking.’ The heavy ploughing brought large stones to the surface which had to be removed or picked out by hand thereby enabling crops to be sown. After the harvest children worked in the fields seeking and collecting any remaining grain left behind. This exercise was known as gleaning , and when collected the grain could be taken to the windmill to be ground into flour for household use.

Attendance at school became compulsory; the logbook states in 1885 that a number of parents were fined for failing to send their children to school. This was intended to ensure that there was no unnecessary interruption to their education. However, it is also logged that when the school had full attendance, they were given a day off!

Many illnesses were experienced, with annual outbreaks of mumps, diphtheria, ringworm, measles, scarlet fever, influenza and bronchitis. Some logbooks record incidents of child deaths caused by these illnesses.

Pupils came from the outlying areas around Croxley Green including Redheath. Many walked to school. This meant negotiating long, rough country lanes which often had no hard surface. Severe weather conditions often prevented infants from attending, particularly during winter months, sometimes from the end of November to early February.

Early records indicate that the children attending Yorke Road School were very fortunate in the high degree of pastoral care shown them as well as the high standard of education they received. Children moved upwards through the school by virtue of improved ability and not necessarily because of age. The pupils were tested in ‘Standards.’ Standard 1 commenced at seven years of age and by age thirteen they were expected to have achieved Standard 7. The range of subjects taught included the normal 3 R’s (this was a term used for reading, writing and arithmetic) as well as marching and drill movements. Having eventually reached a high standard, some pupils became paid monitors and taught the younger children. It is logged that one particular female monitor had 60 children in her care!

When the young boys first started school, Miss Aricie Clarke, Headteacher, introduced them to singing and any boy whose voice showed potential was encouraged to join the church choir.

A favourite venue for the Methodist Chapel Sunday School (sometimes referred to as Primitive Methodist) annual ‘treat’ was Bricket Wood where a popular fair was held on a permanent site. Children who attended this chapel were given a day’s or half day’s holiday from Yorke Road School so that they could attend and those pupils remaining just had time off.

Children were usually seated at desks in rows facing the front, or the very young were given benches to sit on, especially in times of over-crowding. Writing materials could be very scarce and each child was given a small board made of slate and a piece of chalk or possibly a slate pencil to use for their writing and sums. They progressed to desks and paper and pencils as and when these items could be afforded.

The desks had ‘wells’ for ink and writing was achieved using a pen with a metal nib. The desktops lifted up for storing books and pencils used by the pupils. Each pupil sat at the same desk unless moved by the teacher for a specific reason. When the school became very overcrowded the very young were provided with forms to sit on so that they could all be accommodated together!! Heating was by a cast iron stove in each class room.

Games were an important part of the children’s break from school work. Skipping ropes for girls were very popular and if a large one was available and two strong ‘turners’ many children could skip together in the centre of the rope. Wooden spinning tops were also very popular, and these were painted with coloured chalk on top to make fascinating effects when whipped with a stick that had a fine piece of leather attached. Marbles were a favourite with boys and could be ‘flicked’ against a wall or a board. During the autumn time, seeking out conkers (horse chestnut fruits) of the most desirable size and shape could be a serious task, as to win a conker competition was indeed the ultimate goal for a determined school boy. A ‘secret’ but not necessarily an honest ruse was to bake the conker first. After threading it on to a long piece of strong string the boys attempted to smash each other’s conkers by taking swipes at them- hopefully avoiding rapping the opponent’s hand!

The ever increasing population of the village, largely due to the continuing growth of John Dickinson’s Mill, inevitably increased the number of school children during the early 1880’s.This number reached 156 and Her Majesty’s School Inspector became concerned that the school accommodation was inadequate. Accordingly, the main room 50’x 22’ was partitioned. Another room 25’x 18’ was identified for use by the ‘babies’ or infants. In 1888 a letter was sent to the Board of Education requesting that this situation should be remedied and plans were agreed for an extension. A specification for tender was made to local builders and by 1889 enlargements to the school were completed and the number of pupils increased to 235. The infants were now taught by the newly appointed Headmistress, Miss Ellen Martha Walter. Miss Annie Denham was Assistant Mistress and Florence Brown (a fourth standard girl) was “Monitress”.

It would appear that many teachers were not fully trained when they started but following their teaching practice and examinations they would become qualified.

Miss Clarke continued as Headmistress to the older boys and girls aged seven to leaving age.

As more and more housing was erected in the village, the school accommodation for the children became hopelessly inadequate once more. School fees were eventually abolished. In the early 1890’s parents had been expected to pay an annual fee of about 12s 0d per pupil (twelve shillings = approx. 60p) but this could be varied. In June 1893, the logbook shows that ‘The children are not making much progress as the classes are so large. When the children write on paper they have to stand and sit alternately.’ It was decided, following an extensive building programme in 1894 that changes would have to be made. This gave rise to the infants being separated from both the older boys and older girls over seven years of age. The infants, who had seen several changes of Headmistresses since 1889, were currently under Miss Emily Haigh. Miss Aricie Clarke became Headmistress of the older girls to whom were designated the larger rooms of the original school and a separate playground. The older boys, of seven and over, were now moved out to the newly built school in the Watford Road. This was just a short distance away and Mr. Alfred Walter Stratton-Hanes was Headmaster.

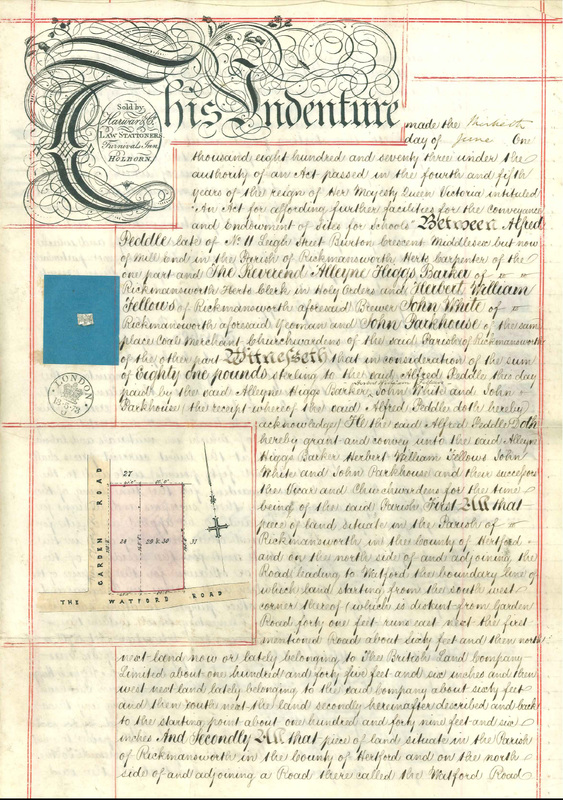

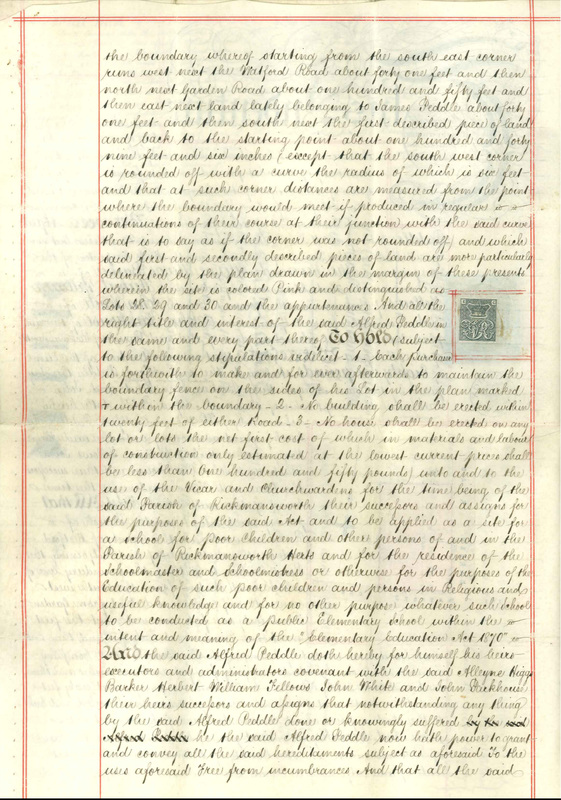

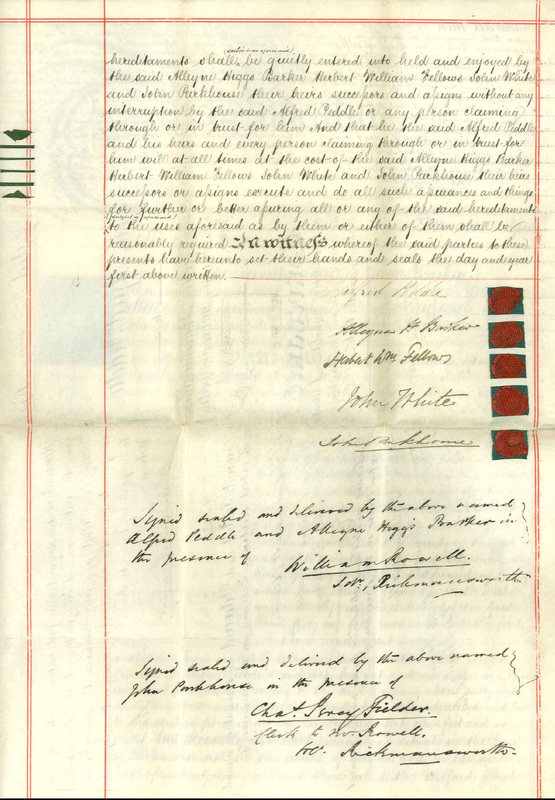

Conveyance of 30 June 1873 to the vicar and churchwardens of Rickmansworth which shows the original trusts on which the school was held (suspended by an Order in Council (ESA 242G) in 1950)

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

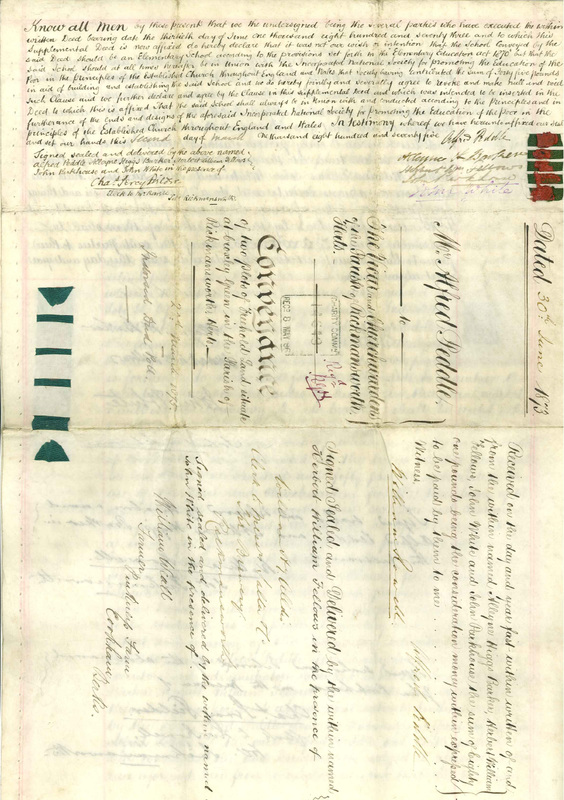

The Charity Commission scheme of 10th January 1888 transferring the trusteeship to the vicar and churchwardens of Croxley Green

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

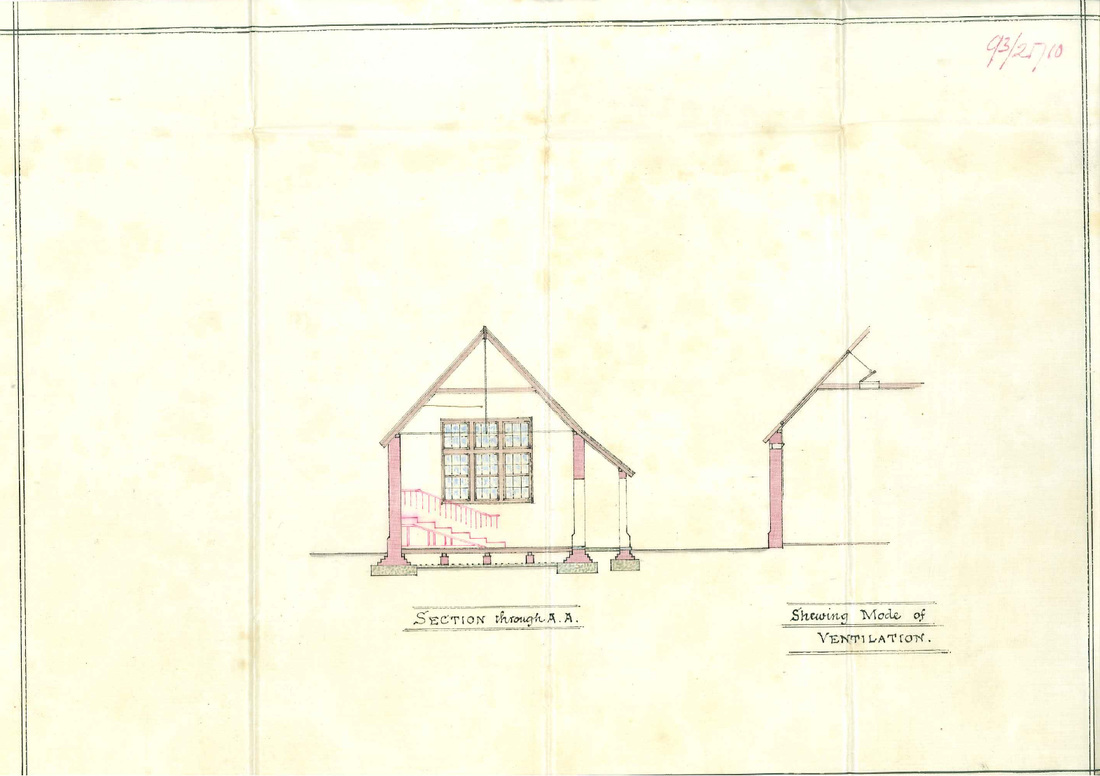

The original plans for Yorke Road School