Croxley Paper Mill during WW2

The mill at Croxley Green served many of the other local mills producing paper in various forms and quality. Even during wartime paper was a valuable commodity and became very difficult in its production as much of the raw material came from overseas and countries such as Norway were occupied by the German army.

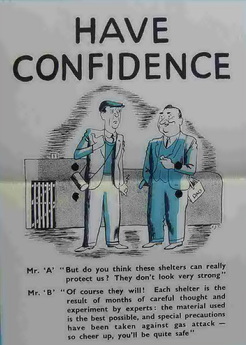

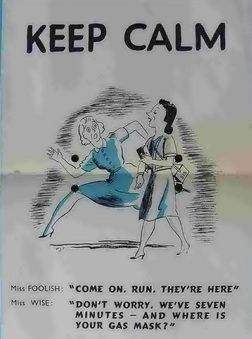

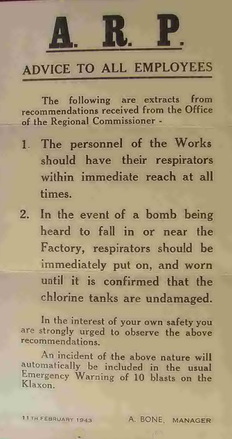

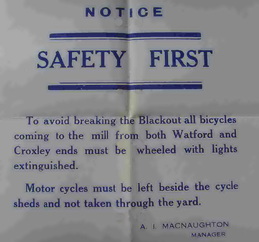

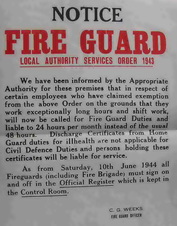

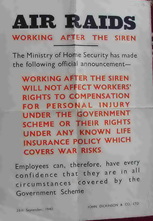

Even before this country joined in 1939, the mill managers were aware of the problems in Europe. Instances of this are shown in the many posters displayed around the buildings. In fact, this was the best means of communication to the workforce and even before WW1, posters notified staff of a whole range of essential information and not necessarily work related.

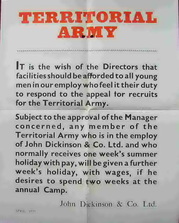

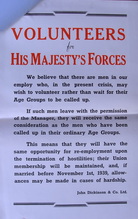

Croxley mills granted many of its staff the opportunity to join the Territorial Army, usually depending on that person’s job and did their best to facilitate the recruitment services. However, as the war progressed many jobs became a reserved occupation and permission to join up was required in the first instance. Allowances to married men with dependants were paid to the family and where possible periodic home visits by a staff member to monitor any hardship problems.

As a highly inflammable product, as well as all the chemicals stored at the mill, safety was paramount and these measures were taken very seriously. The mill formed its own Home Guard as well as fire watching duties. Total black out at night was adhered too as its position would have given the German bombers a clear target. It’s quite feasible the two attempts that hit the top of Scots Hill area could have been aiming for the mill.

Croxley mill began to manufacture board for fuse caps as well as special quality paper for maps. An essential development in WW2 was when the mill began to produce anti-radar paper made to give some protection to the British and American bombers flying over Germany to their targets. Sir Robert Cockburn, a British radar specialist headed a team that made this possible. Metallic strips of paper in small bundles could be dropped from the aircraft some distance from the targets and made them undetected by the German radar systems.

Even though raw materials were difficult to obtain and prices reflected this, the mill survived. Personnel returning when peace was declared with their jobs secure, continued to work at the mill.

Even before this country joined in 1939, the mill managers were aware of the problems in Europe. Instances of this are shown in the many posters displayed around the buildings. In fact, this was the best means of communication to the workforce and even before WW1, posters notified staff of a whole range of essential information and not necessarily work related.

Croxley mills granted many of its staff the opportunity to join the Territorial Army, usually depending on that person’s job and did their best to facilitate the recruitment services. However, as the war progressed many jobs became a reserved occupation and permission to join up was required in the first instance. Allowances to married men with dependants were paid to the family and where possible periodic home visits by a staff member to monitor any hardship problems.

As a highly inflammable product, as well as all the chemicals stored at the mill, safety was paramount and these measures were taken very seriously. The mill formed its own Home Guard as well as fire watching duties. Total black out at night was adhered too as its position would have given the German bombers a clear target. It’s quite feasible the two attempts that hit the top of Scots Hill area could have been aiming for the mill.

Croxley mill began to manufacture board for fuse caps as well as special quality paper for maps. An essential development in WW2 was when the mill began to produce anti-radar paper made to give some protection to the British and American bombers flying over Germany to their targets. Sir Robert Cockburn, a British radar specialist headed a team that made this possible. Metallic strips of paper in small bundles could be dropped from the aircraft some distance from the targets and made them undetected by the German radar systems.

Even though raw materials were difficult to obtain and prices reflected this, the mill survived. Personnel returning when peace was declared with their jobs secure, continued to work at the mill.