Memorial Doors to Commemorate the end of WWI

All Saints Church

Croxley Remembers the First World War - The Memorial Doors

(© Tracey Sheppard) Tracey Sheppard

(© Tracey Sheppard) Tracey Sheppard

Croxley Green has four village memorials to those killed on the battlefields of WWI and later wars: those on the Green, one inside All Saints’ Church and another overlooking the Church’s Garden of Remembrance, recording those killed who had worked at Dickinson’s Mills.

In 2014/15 a village wish arose for a new, and new style of, memorial. The wish was prompted, at least in part, by local historian Brian Thomson’s 2014 book ‘Croxley Green in the First World War: the story of a Hertfordshire village 1914 to 1919’. The new memorial was not to simply duplicate those already existing, but rather prompt reflection of the village from which the men went to war and the effects that The War had on that village, on both the people left behind and those who returned.

In late 2016, with the help of the Diocesan office and the Guild of Glass Engravers, and through pictures of her work and visits to see it in situ, we found exactly the right designer and engraver: Winchester-based Tracey Sheppard. A small steering group was set up representing the village, the Church and the Diocese to brief Tracey and to oversee the project to its completion, including raising the necessary money.

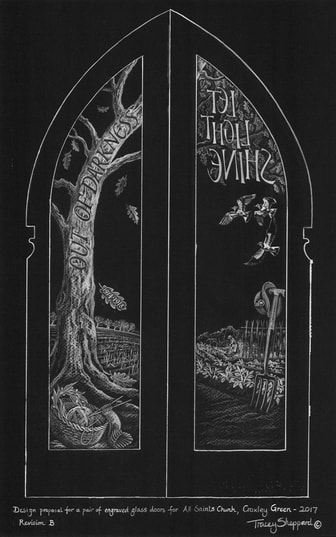

Death in action brought suffering, grief and often destitution to both those left behind and to many of those returning, injured mentally and physically. But there was also resilience, a springing back, a trust in better. The message of Christianity is one of hope and trust. Of something good arising from something bad. Death followed by Resurrection. Tracey’s design contrasts the dark with the light. The words ‘Out of darkness let light shine,’ 2 Corinthians 4:6, offer hope after the tumultuous and terrible events of WW1.

Although hanging in All Saints’ Church, the doors are very much a village project, supported by local fundraising, personal donations, as well as grants from Croxley Green Parish Council, Three Rivers District Council, Herts. County Council, Croxley Green Residents Association and the Croxley Branch of the Royal British Legion, from All Saints’ itself and at a national level, the All Churches Trust. The new doors are a unique and beautiful artwork; a reflection of, and in their own right a piece of, the village’s heritage and perhaps that of the wider world. Perhaps they will inspire reflection of the events of a century ago; how nations and governments sleepwalked into a murderous world-wide conflict; and the

price paid not just by the many millions who gave up their lives on the battlefields, but the many more millions in towns and villages whose lives

were changed by the war, both in the short and much longer term, and its effects at the level of everyday family and village life.

These doors will be a lasting reminder for generations to come: spend time marvelling at the detail, looking for the symbolism but overall thinking about the story that goes with them and enjoying their beauty.

by John Galloway

In 2014/15 a village wish arose for a new, and new style of, memorial. The wish was prompted, at least in part, by local historian Brian Thomson’s 2014 book ‘Croxley Green in the First World War: the story of a Hertfordshire village 1914 to 1919’. The new memorial was not to simply duplicate those already existing, but rather prompt reflection of the village from which the men went to war and the effects that The War had on that village, on both the people left behind and those who returned.

In late 2016, with the help of the Diocesan office and the Guild of Glass Engravers, and through pictures of her work and visits to see it in situ, we found exactly the right designer and engraver: Winchester-based Tracey Sheppard. A small steering group was set up representing the village, the Church and the Diocese to brief Tracey and to oversee the project to its completion, including raising the necessary money.

Death in action brought suffering, grief and often destitution to both those left behind and to many of those returning, injured mentally and physically. But there was also resilience, a springing back, a trust in better. The message of Christianity is one of hope and trust. Of something good arising from something bad. Death followed by Resurrection. Tracey’s design contrasts the dark with the light. The words ‘Out of darkness let light shine,’ 2 Corinthians 4:6, offer hope after the tumultuous and terrible events of WW1.

Although hanging in All Saints’ Church, the doors are very much a village project, supported by local fundraising, personal donations, as well as grants from Croxley Green Parish Council, Three Rivers District Council, Herts. County Council, Croxley Green Residents Association and the Croxley Branch of the Royal British Legion, from All Saints’ itself and at a national level, the All Churches Trust. The new doors are a unique and beautiful artwork; a reflection of, and in their own right a piece of, the village’s heritage and perhaps that of the wider world. Perhaps they will inspire reflection of the events of a century ago; how nations and governments sleepwalked into a murderous world-wide conflict; and the

price paid not just by the many millions who gave up their lives on the battlefields, but the many more millions in towns and villages whose lives

were changed by the war, both in the short and much longer term, and its effects at the level of everyday family and village life.

These doors will be a lasting reminder for generations to come: spend time marvelling at the detail, looking for the symbolism but overall thinking about the story that goes with them and enjoying their beauty.

by John Galloway

|

These doors were made possible thanks to the generous donations from many organisations and individuals, including the following:

Organisations who donated: Hertfordshire County Council Locality Fund Three Rivers District Council Croxley Green Parish Council Croxley Green Residents Association Windmill Drive Residents Association All Churches Trust All Saints’ Church Croxley Branch of the Royal British Legion Croxley Green Flower Group Fundraising events: Not about Heroes Croxley Revels Concert by Chiltern Brass Band Individuals: Pam and Alan Bluff Shelagh and Tony Booth Alick and Hazel Burge Anne and Malcolm Elliott Chris Fagan Pat Foster John Galloway Edna Holden Sheila and Trevor Humphrey Val Hunt Gill and Brian Main Judith and David Muir Andrew Nobbs Anne and Chris Oke Dorothy Sims Norma Stone Joan and David Tait Brian and Gill Thomson Barbara Wilbee Hazel Willoughby |

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918 What it meant for the people of Croxley Green

by Brian Thomson (See Brian Thomson “Croxley Green in the First World War”, Rickmansworth Historical Society 2014 )

The Village in 1914

In 1914, Croxley Green, located midway between the market towns of Watford and Rickmansworth, had a population of about 2,400. The settlement comprised a few houses and farms near the Green, a cluster of cottages and shops at the top of Scots Hill and the houses and shops along New Road, which linked the ancient Green with John Dickinson and Co’s paper mill by the canal.

Croxley Mills were, by far, the largest employer in the village. The mill, and the settlement’s small size, gave the place a different character from the larger towns of Rickmansworth and Watford and from more agricultural places nearby such as Sarratt and Chorleywood. People knew each other well, both at work and in their social hours.

The Dickinson Institute, in New Road, was the hub of community life. It offered facilities for adult education and a wide range of social activities.

The buildings were enlarged in 1904 and, in 1914, they provided a men’s club, women’s and girls’ club, lads’ brigade, technical school, laboratory, library, billiard room, recreation and refreshment rooms and an entertainment hall to seat 600 people.

In 1914, Croxley Green, located midway between the market towns of Watford and Rickmansworth, had a population of about 2,400. The settlement comprised a few houses and farms near the Green, a cluster of cottages and shops at the top of Scots Hill and the houses and shops along New Road, which linked the ancient Green with John Dickinson and Co’s paper mill by the canal.

Croxley Mills were, by far, the largest employer in the village. The mill, and the settlement’s small size, gave the place a different character from the larger towns of Rickmansworth and Watford and from more agricultural places nearby such as Sarratt and Chorleywood. People knew each other well, both at work and in their social hours.

The Dickinson Institute, in New Road, was the hub of community life. It offered facilities for adult education and a wide range of social activities.

The buildings were enlarged in 1904 and, in 1914, they provided a men’s club, women’s and girls’ club, lads’ brigade, technical school, laboratory, library, billiard room, recreation and refreshment rooms and an entertainment hall to seat 600 people.

The village had three churches, seven pubs (if you include the Half Way House at Cassiobridge) as well as ‘refreshment rooms’ in Scots Hill. It boasted two banks, a building society, two insurance agents and a full complement of shops including the Co-operative, a couple of Post Offices, several grocers, butchers, greengrocers, a newsagents, druggist and drapers. You could buy freshly made bread from two bakers and there were three dairymen to provide milk.

If you needed shoes mending there were several bootmakers and a couple of laundries too. There were two hairdressers, a builder and a music teacher. Dr. Evans looked after villagers’ health and Constable Haggar kept any unruly elements in check. Most Croxley children attended the elementary schools in Yorke Road and Watford Road. Bearing in mind the number of itinerant tradesmen visiting Croxley Green in those days, it would have been possible to live a pleasant and busy life without leaving

the village.

The countryside was close by in the surrounding farms: Parrots, Killingdown, Croxley Hall, Rousebarn, Redheath, Loudwater and Micklefield. In spring, the orchards surrounding the Green were a picture of white blossom. Serving the farming community were a blacksmith and wheelwright. Croxley Green even had its own ‘cycle and motor maker’ (Mr. Kemp of Scots Hill).

Down the hill towards Watford, there was a cluster of businesses alongside the canal and River Gade: a timber merchant, a builder’s yard and the watercress farm of the Sansom family. At Scotsbridge Mill, towards Rickmansworth, Rexam Ltd made photographic paper and there were more watercress beds at Croxley Hall Farm and in the Chess Valley.

If, however, one had to venture further afield, the London and North Western Railway had opened their branchline from Watford to Croxley Green, near Cassiobridge, in 1912 and there was a regular bus service connecting the village to Watford and Rickmansworth where the main line railways were well established.

The convenience of the railway and the pleasant aspect of the Chess Valley meant that Croxley was home to some wealthy commuters, even in 1914. For example, Samuel Ingleby Oddie, who lived at Chess Side in Copthorne Road, was a London coroner and William Catesby, of Highfield on Scots Hill, ran a London furniture emporium. They both played an important role in local affairs.

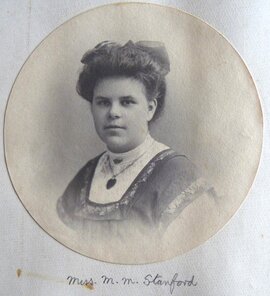

There are a few local residents whose names crop up again and again. Charles Barton-Smith, General Manager of Croxley Mills from 1899 to 1918, was head and shoulders above the others. He was immensely influential in the life of the village as employer, as chairman and treasurer of the Dickinson Institute, as churchwarden at All Saints’ and as a member of Rickmansworth Urban District Council. William Richard Woolrych, of Croxley House, was the main resident landowner. He rather fitted the image of local squire as Justice of the Peace on the Watford Bench, one of the Guardians of the Watford Union Workhouse, chairman of the local Conservative and Unionist Association and chairman of the Rifle Club. Rev. Edward Wells was the vicar. For many local residents, the Heads of the Elementary Schools played a formative role. Aricie Clarke was the Head of the Girls’ School and H. T. ‘Neggy’ Wilson of the Boys’. Neggy was also, for a time, choirmaster at All Saints’ Church and something of a local institution. Miss Clarke retired in July 1915 and was succeeded by Mildred Stanford.

the village.

The countryside was close by in the surrounding farms: Parrots, Killingdown, Croxley Hall, Rousebarn, Redheath, Loudwater and Micklefield. In spring, the orchards surrounding the Green were a picture of white blossom. Serving the farming community were a blacksmith and wheelwright. Croxley Green even had its own ‘cycle and motor maker’ (Mr. Kemp of Scots Hill).

Down the hill towards Watford, there was a cluster of businesses alongside the canal and River Gade: a timber merchant, a builder’s yard and the watercress farm of the Sansom family. At Scotsbridge Mill, towards Rickmansworth, Rexam Ltd made photographic paper and there were more watercress beds at Croxley Hall Farm and in the Chess Valley.

If, however, one had to venture further afield, the London and North Western Railway had opened their branchline from Watford to Croxley Green, near Cassiobridge, in 1912 and there was a regular bus service connecting the village to Watford and Rickmansworth where the main line railways were well established.

The convenience of the railway and the pleasant aspect of the Chess Valley meant that Croxley was home to some wealthy commuters, even in 1914. For example, Samuel Ingleby Oddie, who lived at Chess Side in Copthorne Road, was a London coroner and William Catesby, of Highfield on Scots Hill, ran a London furniture emporium. They both played an important role in local affairs.

There are a few local residents whose names crop up again and again. Charles Barton-Smith, General Manager of Croxley Mills from 1899 to 1918, was head and shoulders above the others. He was immensely influential in the life of the village as employer, as chairman and treasurer of the Dickinson Institute, as churchwarden at All Saints’ and as a member of Rickmansworth Urban District Council. William Richard Woolrych, of Croxley House, was the main resident landowner. He rather fitted the image of local squire as Justice of the Peace on the Watford Bench, one of the Guardians of the Watford Union Workhouse, chairman of the local Conservative and Unionist Association and chairman of the Rifle Club. Rev. Edward Wells was the vicar. For many local residents, the Heads of the Elementary Schools played a formative role. Aricie Clarke was the Head of the Girls’ School and H. T. ‘Neggy’ Wilson of the Boys’. Neggy was also, for a time, choirmaster at All Saints’ Church and something of a local institution. Miss Clarke retired in July 1915 and was succeeded by Mildred Stanford.

|

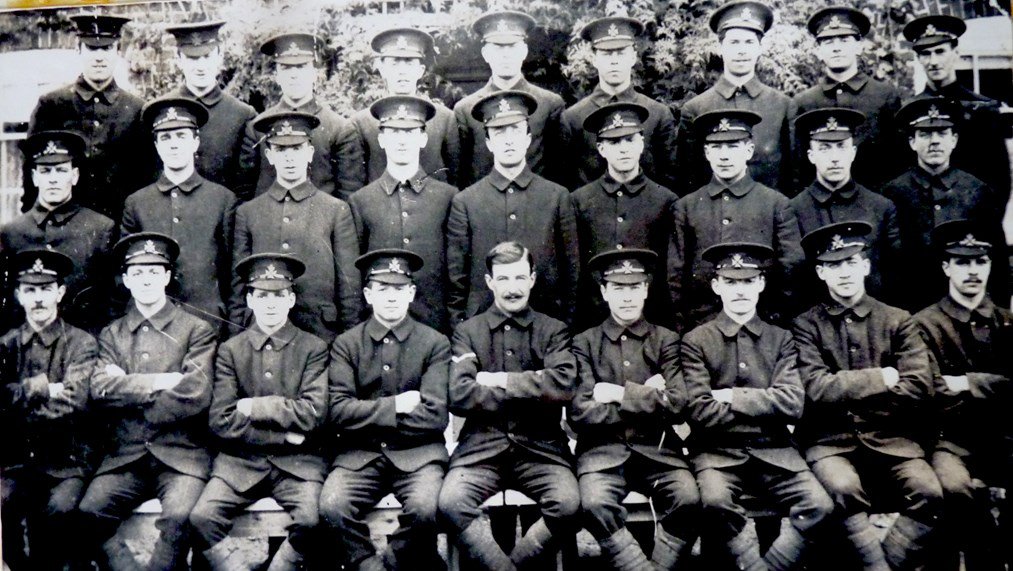

As elsewhere in the country, most Croxley people responded with great patriotism at the outbreak of war in August 1914. Croxley Mills encouraged their workers to join up if they were not essential to the manufacturing process. They opened their rifle range for practice by local men and provided some of their land for allotments. The Dickinson Institute was offered to the Red Cross as the site for a hospital.

|

|

The roll of honour in All Saints’ Church lists 109 local men who joined the forces in 1914. Notable amongst them were 41 ex-members of the Church Lads’ Brigade, many of whom worked at Croxley Mills. All Saints’ Church donated their harvest gifts for the benefit of Belgian refugees and Miss Barker, of Briery Court, convened the ladies War Working Party which made garments for servicemen and collected clothing for the refugees. This enthusiasm was coupled with real fear of a German invasion and bombing from Zeppelins. A local company of volunteers was formed from men who could not join the forces.

|

|

As the war dragged on it brought hardship and loss. The All Saints’ roll includes over 350 names of men from the village who enlisted. That is almost certainly an underestimate. In practical terms it meant that, by the end of 1916, there were very few young men in the village. Croxley Mills relied increasingly on women, veterans and boys to continue production and the same was true of other local businesses. By May 1916, the Red Cross Hospital was in full operation at the Dickinson Institute. The convalescing soldiers relied on many local volunteers.

|

|

By 1917, the war’s toll of death and destruction was undermining morale and food became scarce. Farmers were required to convert grassland to grow food crops and people increasingly grew their own food on new allotments. The Women’s Land Army was officially launched in January 1918 to help farmers who were short of labour.

Even schoolchildren were involved in the war effort. The pupils at Croxley Girls’ School knitted socks for soldiers, raised money, collected waste paper and saved their pennies in War Bonds. They proved a formidable bunch - beating the local boys at tug-of-war in both 1918 and 1919! The voting lists for the 1918 election give some idea of the impact of war service on the village. Those eligible to vote were women aged over 30 and men aged over 21. There were 1,167 electors in Croxley Green of whom 274, almost a quarter, were away on war service. That did not include those, mainly women, serving in the Red Cross and similar organisations. |

11 November 1918

After the long years of war and the bitter toll of death and wounding, the armistice brought rejoicing. Church bells rang, schoolchildren assembled with patriotic flags at the Dickinson Institute and convalescing soldiers were delighted that the fighting had stopped. Several of the servicemen made short speeches. So did Mr Kennedy, one of the local magistrates, whose wife was the hospital commandant. Everyone cheered.

After the long years of war and the bitter toll of death and wounding, the armistice brought rejoicing. Church bells rang, schoolchildren assembled with patriotic flags at the Dickinson Institute and convalescing soldiers were delighted that the fighting had stopped. Several of the servicemen made short speeches. So did Mr Kennedy, one of the local magistrates, whose wife was the hospital commandant. Everyone cheered.

Aftermath

The village had paid a heavy price and some families had suffered badly. There was Mrs. Sarah Goodman at number 254 New Road. Before the war, her two young sons enjoyed being part of the Church Lads’ Brigade. Both William and John had died in the fighting of 1916. Then there was Alice Randall at number 261, Fred’s widow, left on her own to bring up young Freddy, Ada and Edward. George Mead at number 179, who worked at the mill, lost two sons, Edwin and Ernest. And it wasn’t just the ordinary village folk who suffered. The Newall family in the big house at Redheath had lost Leslie and Nigel, both second lieutenants in the army. Many of the village’s young men would not come back. Moreover, the influenza epidemic was raging, so even those at home were dying. They included Sir Guy Spencer Calthrop of Croxley House, the Government’s Coal Controller. 57 servicemen who died in the conflict are recognised on the village War Memorial. There are others who were born or lived in the village who were killed who ought to be recognised too.

Those who did return often suffered from mental and physical wounds which they and their families had to deal with. Sometimes it was too much, as for Walter Sims who suffered from severe mental illness and died in 1922. Thomas Plumridge was invalided from the army with chest wounds and soon developed TB. He managed to return to work at Croxley Mills but died soon afterwards in 1925.

In general, people made the best of it. A good example was Susan Newberry, whose parents ran the Duke of York pub in Watford Road. It hit the family hard when two of her brothers, Samuel and John, were killed.

But, in 1924, there was celebration when she married George Howard. Susan had chosen a man who had lost a leg at the Somme in 1918. Together they brought up three children. George was a remarkable man in spite of his handicap. In 1935 he was presented with a certificate from the Royal Humane Society for rescuing two people from drowning in the canal.

The village had paid a heavy price and some families had suffered badly. There was Mrs. Sarah Goodman at number 254 New Road. Before the war, her two young sons enjoyed being part of the Church Lads’ Brigade. Both William and John had died in the fighting of 1916. Then there was Alice Randall at number 261, Fred’s widow, left on her own to bring up young Freddy, Ada and Edward. George Mead at number 179, who worked at the mill, lost two sons, Edwin and Ernest. And it wasn’t just the ordinary village folk who suffered. The Newall family in the big house at Redheath had lost Leslie and Nigel, both second lieutenants in the army. Many of the village’s young men would not come back. Moreover, the influenza epidemic was raging, so even those at home were dying. They included Sir Guy Spencer Calthrop of Croxley House, the Government’s Coal Controller. 57 servicemen who died in the conflict are recognised on the village War Memorial. There are others who were born or lived in the village who were killed who ought to be recognised too.

Those who did return often suffered from mental and physical wounds which they and their families had to deal with. Sometimes it was too much, as for Walter Sims who suffered from severe mental illness and died in 1922. Thomas Plumridge was invalided from the army with chest wounds and soon developed TB. He managed to return to work at Croxley Mills but died soon afterwards in 1925.

In general, people made the best of it. A good example was Susan Newberry, whose parents ran the Duke of York pub in Watford Road. It hit the family hard when two of her brothers, Samuel and John, were killed.

But, in 1924, there was celebration when she married George Howard. Susan had chosen a man who had lost a leg at the Somme in 1918. Together they brought up three children. George was a remarkable man in spite of his handicap. In 1935 he was presented with a certificate from the Royal Humane Society for rescuing two people from drowning in the canal.

Remembrance

The war ended with the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919 and Croxley Green celebrated with a village procession that July. But it was still a time of mourning for those families who had not been able to bury the men they had lost. All Saints’ Church had created its war shrine in 1917, on which were the names of all those who had served from the village.

But people felt that additional ways of remembering were needed. So, on the first anniversary of the armistice in 1919, an oak tree was planted on the Green. In 1921 Rickmansworth Urban District Council dedicated its Memorial for the dead in Rickmansworth and John Dickinson and Co. did the same at Croxley Mills a year later. Not long afterwards, the memorial stones were erected beside the oak tree on the Green with the inscription “and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations”2 which is taken from St John’s vision of a new heaven and new earth in the book of Revelation. For the people of Croxley Green, the memorial oak tree was a symbol of life and hope for the future.

2 Revelation chapter 22, verse 2

The war ended with the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919 and Croxley Green celebrated with a village procession that July. But it was still a time of mourning for those families who had not been able to bury the men they had lost. All Saints’ Church had created its war shrine in 1917, on which were the names of all those who had served from the village.

But people felt that additional ways of remembering were needed. So, on the first anniversary of the armistice in 1919, an oak tree was planted on the Green. In 1921 Rickmansworth Urban District Council dedicated its Memorial for the dead in Rickmansworth and John Dickinson and Co. did the same at Croxley Mills a year later. Not long afterwards, the memorial stones were erected beside the oak tree on the Green with the inscription “and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations”2 which is taken from St John’s vision of a new heaven and new earth in the book of Revelation. For the people of Croxley Green, the memorial oak tree was a symbol of life and hope for the future.

2 Revelation chapter 22, verse 2

Post-War Transformation

Soon the small tight-knit village began to change. In 1921, the District Council built its first council houses in Gonville Avenue. Then, in 1925, the Metropolitan Railway branchline opened and over the next ten years much of the surrounding farmland became houses, welcoming many new families to Croxley Green.

Soon the small tight-knit village began to change. In 1921, the District Council built its first council houses in Gonville Avenue. Then, in 1925, the Metropolitan Railway branchline opened and over the next ten years much of the surrounding farmland became houses, welcoming many new families to Croxley Green.

Doors in Production

Out of Darkness Let Light Shine

© Tracey Sheppard

© Tracey Sheppard

The design and symbolism of the doors spring from the words ‘Out of darkness let light shine,’ 2 Corinthians 4:6.

In the left hand panel, the first three words of the phrase are carved into the trunk of an oak tree, offering those entering the church the chance to come ‘Out of darkness’. An oak tree on The Green was planted at the suggestion of the then headmaster of the Boys’ School, H. T. ‘Neggy’ Wilson, “in memory of those men from the village who had died in the war.” In Christian symbolism, oak trees are often used to represent the cross; here the oak tree is a main part of the design, as well as its frame.

The tree’s branches are bare, their leaves falling and reminding us of the lives lost. The tree grows in a barren landscape where only broken stubble and ridges of old furrows remain. These could be seen to represent the trenches of the battlefields. An abandoned basket lies at the tree’s base. In it is a half finished sock, suggesting that the knitter has lost the man for whom she was making it. Making socks for ‘Tommy’ was something that the women of Britain were called upon to do as part of the war effort. The basket also holds a laurel wreath. Laurel is a symbol of triumph and eternity. It became a tradition for the girls of Croxley Green to make laurel festoons for the railings that surround the memorial oak as an act of commemoration. The memorial plaque on the south wall of the church has a broad decorative band of laurel.

The tree branches spread across the top of the right-hand panel of the doors, where they are no longer bare but now full of leaf and so life, perhaps suggesting the resurrection. The second half of the quotation, ‘Let light shine’, sits amongst the leaves and can be read from inside the church as a message to carry out into the world.

A trio of birds fly across the glass – birds have often been used to signify the soul being released to fly heavenwards. These particular birds are lapwings which villager Frank Paddick recalls seeing in ‘great flocks which flew round and round the village’ in his book ‘A Village Boyhood in Croxley Green’ 3. They would have been a sight familiar to the local men who had gone away to war.

The land beneath is full of signs of growing food. Croxley was farming country. The nation still had to be fed, even with its men now digging trenches and burying their comrades rather than tilling fields.

3. ‘A Village Boyhood in Croxley Green’ by Frank Paddick, Rickmansworth Historical Society 2012

In the left hand panel, the first three words of the phrase are carved into the trunk of an oak tree, offering those entering the church the chance to come ‘Out of darkness’. An oak tree on The Green was planted at the suggestion of the then headmaster of the Boys’ School, H. T. ‘Neggy’ Wilson, “in memory of those men from the village who had died in the war.” In Christian symbolism, oak trees are often used to represent the cross; here the oak tree is a main part of the design, as well as its frame.

The tree’s branches are bare, their leaves falling and reminding us of the lives lost. The tree grows in a barren landscape where only broken stubble and ridges of old furrows remain. These could be seen to represent the trenches of the battlefields. An abandoned basket lies at the tree’s base. In it is a half finished sock, suggesting that the knitter has lost the man for whom she was making it. Making socks for ‘Tommy’ was something that the women of Britain were called upon to do as part of the war effort. The basket also holds a laurel wreath. Laurel is a symbol of triumph and eternity. It became a tradition for the girls of Croxley Green to make laurel festoons for the railings that surround the memorial oak as an act of commemoration. The memorial plaque on the south wall of the church has a broad decorative band of laurel.

The tree branches spread across the top of the right-hand panel of the doors, where they are no longer bare but now full of leaf and so life, perhaps suggesting the resurrection. The second half of the quotation, ‘Let light shine’, sits amongst the leaves and can be read from inside the church as a message to carry out into the world.

A trio of birds fly across the glass – birds have often been used to signify the soul being released to fly heavenwards. These particular birds are lapwings which villager Frank Paddick recalls seeing in ‘great flocks which flew round and round the village’ in his book ‘A Village Boyhood in Croxley Green’ 3. They would have been a sight familiar to the local men who had gone away to war.

The land beneath is full of signs of growing food. Croxley was farming country. The nation still had to be fed, even with its men now digging trenches and burying their comrades rather than tilling fields.

3. ‘A Village Boyhood in Croxley Green’ by Frank Paddick, Rickmansworth Historical Society 2012

|

A single figure dressed in a pinafore and long skirts digs up potatoes. She represents the many women who found themselves not only home-makers but obliged to take up the role of agricultural labourers filling in for the men who were away fighting. In the foreground, a fork is left standing with a Woman’s Land Army hat hanging on the handle. Either the owner has taken a break from her labours, or the war has ended and neither are needed by her any more. Both the fork and the hat also serve as a reminder that the role of women in Croxley Green, as in the wider world, was changed forever by the Great War.

by Tracey Sheppard |