The Railway to Croxley Green

The Metropolitan railway was probably the smallest line serving Hertfordshire. However, the story of its construction is rather interesting.

Some 150 years ago the streets of London and particularly the City were often congested with horse- drawn traffic. Traffic management was non- existent and the constant problem of vast quantities of horse manure can be left to the imagination!

Charles Pearson, a solicitor in the City of London believed that a railway would solve the problem of traffic chaos. It was largely due to his efforts that the North Metropolitan Railway Company was formed in 1854, resulting some ten years later in the opening of the world’s first underground railway.

Later, another company was formed to build a line from Baker Street to what were then the outer suburbs of St John’s Wood. Eventually the North Metropolitan, which was the largest shareholder, absorbed this smaller company.

In 1874 Edward Watkins became Chairman of the company. He was farsighted and he persuaded the shareholders to develop and extend the line north via St John’s Wood to Harrow and then on to Rickmansworth arriving there in 1887. The branch from Moor Park to Watford and electrification was achieved some forty years later.

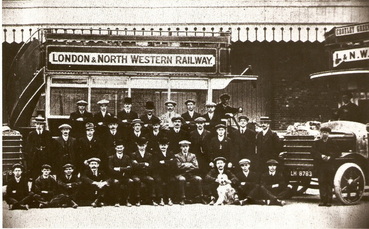

By 1890 Watford had become a substantial market town. Its railway connection was provided by the London & North Western (LNWR) by way of the Junction Station to the North East. As Watford continued to expand and prosper it became apparent that improved and increased provision was essential.

In 1895 the Watford Tradesmen Association suggested to the Metropolitan Railway the construction of a branch line connecting the service to Watford. A reported proposal connecting Watford to Wembley Park failed to materialise. The tradesmen continued their efforts and gained the support of the Urban District Council. In 1904 a public petition gained 1402 signatures supporting a branch line to Watford.

A survey was carried out in 1906 and a route going alongside the Watford to Rickmansworth road was under consideration but access through the Cassiobury estate was unavailable. Some sixty years earlier the Earl of Essex had denied main line access through Cassiobury Park but the LNWR problem was solved by construction of the Watford Tunnels to the North East.

Some 150 years ago the streets of London and particularly the City were often congested with horse- drawn traffic. Traffic management was non- existent and the constant problem of vast quantities of horse manure can be left to the imagination!

Charles Pearson, a solicitor in the City of London believed that a railway would solve the problem of traffic chaos. It was largely due to his efforts that the North Metropolitan Railway Company was formed in 1854, resulting some ten years later in the opening of the world’s first underground railway.

Later, another company was formed to build a line from Baker Street to what were then the outer suburbs of St John’s Wood. Eventually the North Metropolitan, which was the largest shareholder, absorbed this smaller company.

In 1874 Edward Watkins became Chairman of the company. He was farsighted and he persuaded the shareholders to develop and extend the line north via St John’s Wood to Harrow and then on to Rickmansworth arriving there in 1887. The branch from Moor Park to Watford and electrification was achieved some forty years later.

By 1890 Watford had become a substantial market town. Its railway connection was provided by the London & North Western (LNWR) by way of the Junction Station to the North East. As Watford continued to expand and prosper it became apparent that improved and increased provision was essential.

In 1895 the Watford Tradesmen Association suggested to the Metropolitan Railway the construction of a branch line connecting the service to Watford. A reported proposal connecting Watford to Wembley Park failed to materialise. The tradesmen continued their efforts and gained the support of the Urban District Council. In 1904 a public petition gained 1402 signatures supporting a branch line to Watford.

A survey was carried out in 1906 and a route going alongside the Watford to Rickmansworth road was under consideration but access through the Cassiobury estate was unavailable. Some sixty years earlier the Earl of Essex had denied main line access through Cassiobury Park but the LNWR problem was solved by construction of the Watford Tunnels to the North East.

The LNWR stepped up their efforts to thwart other competition and in 1906 introduced a bus service with a Milnes – Daimler double- decker vehicle operating an hourly service between the Junction Station and Croxley Green.

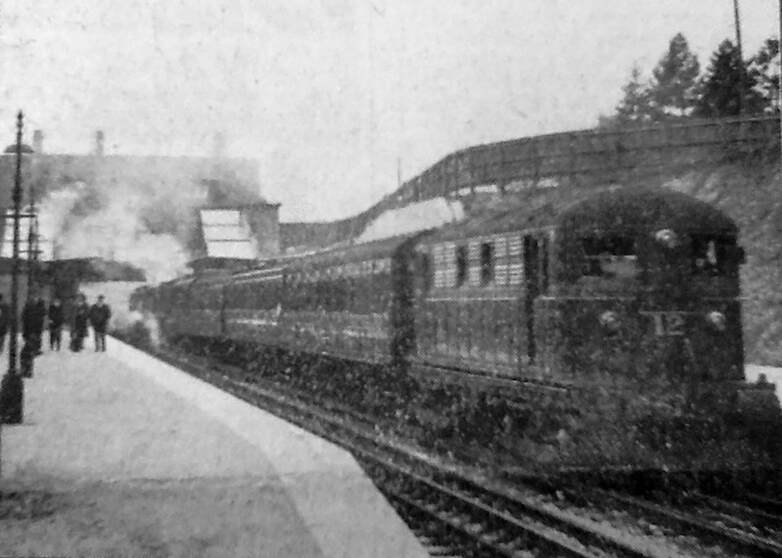

The LNWR had heard of the Metropolitan project for a branch line into the north-west of Watford so they swiftly put into operation their own plans to build a spur from the Watford line to Cassio Bridge with an intermediate station at West Watford. Approval was granted in 1907 and the line opened to traffic in June 1912 with a shuttle service of 22 trains a day.

The LNWR had heard of the Metropolitan project for a branch line into the north-west of Watford so they swiftly put into operation their own plans to build a spur from the Watford line to Cassio Bridge with an intermediate station at West Watford. Approval was granted in 1907 and the line opened to traffic in June 1912 with a shuttle service of 22 trains a day.

The following year on Sunday 9th March 1913 a group of young ladies - travelling through Croxley Green, - enquired as to the whereabouts of the new Croxley Green railway station. It appears from recollections handed down that PC Hagger, the Croxley Green bobby who was renowned for being a very polite, helpful and courteous fellow, showed them the way to the station. Reports later gave rise to suspicion that they may have been suffragettes. In any event during the early hours of Monday morning 10th March an incendiary device at Croxley Green station set fire to the stairs from the road up to the platform which was completely destroyed!

The Construction from Croxley Hall Woods to Watford Metropolitan Station

Although the Metropolitan company had appeared to withdraw and lose interest, a new opportunity arose when land on the Cassiobury Estate came on the market. The Earl of Essex sold part of the land to a building syndicate and part to the Watford Urban District Council which used some 50 acres for a public park. A railway station site was agreed on part of the land allocated for housing. A Bill was laid before the 1912 Parliamentary session seeking permission to construct a branch from Croxley Hall farm to a terminus west of the Hempstead Road, Watford.

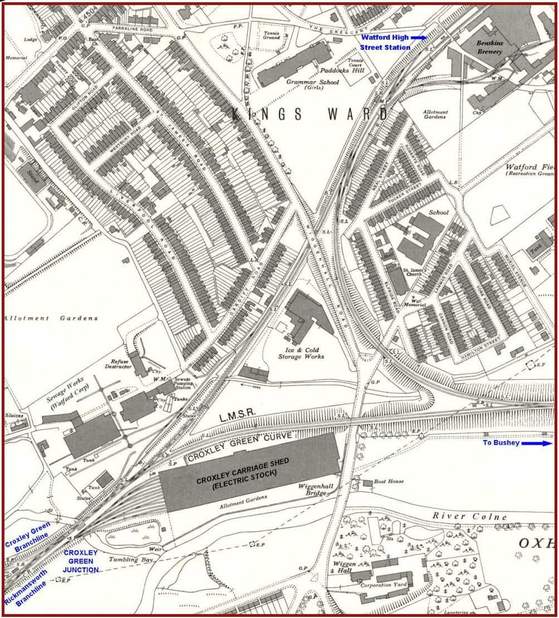

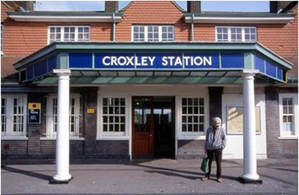

It was planned to lay the line on the east side of Croxley Green and north-west of the main road through Croxley Green community, - skirting the Watford Grammar School for boys. An intermediate station was proposed at Croxley Green and also a halt to serve the Watford Golf Course.

LNWR objected to part of the layout, apparently to cause as much difficulty as possible in order to thwart these plans. Their stated intention was to consider at some future date an extension from their Croxley Green terminus to Tring.

Eventually it was agreed to raise the height of the Metropolitan line so that the LNWR line could pass underneath. It was also necessary for the Metropolitan to raise the height of the embankment to cope with the canal crossing.

A siding was created off a branch from the main line at Croxley Hall farm. This catered for the operations of the Rickmansworth Gravel Company. The company had excavations in Long Valley Wood for gravel and had a washing and grading plant by the canal below Common Moor lock. Here, the granite edging of the wharf can still be seen on the canal bank. The Metropolitan branch to Watford ran across the gravel company sidings. Following negotiations these had to be moved and replaced by a new point of access to the plant. Early 20th century maps show the site of the original sidings - It is a point of interest that the washed gravel used in the construction of the original Wembley Stadium to form part of the British Empire Exhibition of 1924 passed through this site.

The proposed line gained royal assent in August 1912 but the start of the First World War in 1914 meant that the building of the branch line had to be postponed. However, the purchase of land continued. Much came from Gonville and Caius, College, with Cambridge University one acquisition of 37 acres costing £490 an acre. In 1916 land owner Mr Greves of Cassio Bridge House was reported as “a troublesome case in relation to the development at Croxley Hall farm of a terminus west of the Hempstead Road obtaining part of his land for the Watford extension”. The problem was overcome by agreeing to build an ornamental bridge giving this gentleman private access to Cassio Bridge House.

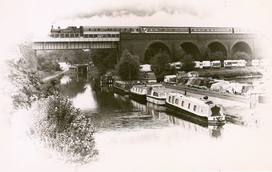

The Government, which had assumed control of the railways during WW1, amalgamated 123 railways in 1924 to form four groups, thereby facilitating economic operation. Competition from road vehicles was increasing. The effect of the amalgamation on the Metropolitan was the formation of a joint London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) and Metropolitan Committee to replace the Great Central and Metropolitan. A review of the development plans took place and in 1923 with all the required land already purchased the contract to build the line was let to the lowest tender. This came from Messrs Logan and Hemmingway of Doncaster offering to complete in 21 months. The contractors however, found the construction much more difficult than they had anticipated. There were over 2½ miles of track to be laid and 10 bridges to be built that were of considerable height in order to cross the canal and the River Gade.

It was planned to lay the line on the east side of Croxley Green and north-west of the main road through Croxley Green community, - skirting the Watford Grammar School for boys. An intermediate station was proposed at Croxley Green and also a halt to serve the Watford Golf Course.

LNWR objected to part of the layout, apparently to cause as much difficulty as possible in order to thwart these plans. Their stated intention was to consider at some future date an extension from their Croxley Green terminus to Tring.

Eventually it was agreed to raise the height of the Metropolitan line so that the LNWR line could pass underneath. It was also necessary for the Metropolitan to raise the height of the embankment to cope with the canal crossing.

A siding was created off a branch from the main line at Croxley Hall farm. This catered for the operations of the Rickmansworth Gravel Company. The company had excavations in Long Valley Wood for gravel and had a washing and grading plant by the canal below Common Moor lock. Here, the granite edging of the wharf can still be seen on the canal bank. The Metropolitan branch to Watford ran across the gravel company sidings. Following negotiations these had to be moved and replaced by a new point of access to the plant. Early 20th century maps show the site of the original sidings - It is a point of interest that the washed gravel used in the construction of the original Wembley Stadium to form part of the British Empire Exhibition of 1924 passed through this site.

The proposed line gained royal assent in August 1912 but the start of the First World War in 1914 meant that the building of the branch line had to be postponed. However, the purchase of land continued. Much came from Gonville and Caius, College, with Cambridge University one acquisition of 37 acres costing £490 an acre. In 1916 land owner Mr Greves of Cassio Bridge House was reported as “a troublesome case in relation to the development at Croxley Hall farm of a terminus west of the Hempstead Road obtaining part of his land for the Watford extension”. The problem was overcome by agreeing to build an ornamental bridge giving this gentleman private access to Cassio Bridge House.

The Government, which had assumed control of the railways during WW1, amalgamated 123 railways in 1924 to form four groups, thereby facilitating economic operation. Competition from road vehicles was increasing. The effect of the amalgamation on the Metropolitan was the formation of a joint London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) and Metropolitan Committee to replace the Great Central and Metropolitan. A review of the development plans took place and in 1923 with all the required land already purchased the contract to build the line was let to the lowest tender. This came from Messrs Logan and Hemmingway of Doncaster offering to complete in 21 months. The contractors however, found the construction much more difficult than they had anticipated. There were over 2½ miles of track to be laid and 10 bridges to be built that were of considerable height in order to cross the canal and the River Gade.

The line laid to access the route

The line laid to access the route

The work commenced with the building of a ‘contractor’s railway line’ from one end of the site to the other. The line commenced at the gravel sidings by the canal below Common Moor lock. It was laid in the early American style with flat-bottom rails which were spiked to sleepers. It looked rather like a big dipper as it crossed the undulating countryside of Croxley Green and Cassiobury to Watford.

The route then was mostly open farmland. At this time the area of New Road was gradually being developed and the first Council housing was being built in Gonville Avenue. The new line was to go through Croxley Hall woods to the future locations of Harvey Road and along the back of the proposed Frankland Road to a level crossing at the Watford Road.

The route then was mostly open farmland. At this time the area of New Road was gradually being developed and the first Council housing was being built in Gonville Avenue. The new line was to go through Croxley Hall woods to the future locations of Harvey Road and along the back of the proposed Frankland Road to a level crossing at the Watford Road.

This was to be the position of the second Croxley Green Station - A small row of some six or so cottages had to be demolished for this purpose. To compensate for the demolition, the Metropolitan built new dwellings further along the Watford Road. These new houses were of concrete construction which was a new concept at that time. The ground in this vicinity opposite the Red House public house had been the scene of many locally celebrated sporting events. John Dickinson had leased the land from Gonville & Caius College Cambridge University, for recreational purposes and now a railway cutting was to pass right through it!

Albert Freeman, the Rickmansworth Urban District surveyor had many confrontations with the company. Apparently, in the early planning stages the Metropolitan had taken tenancy of various sites in the area around the station. In particular, sites at Gonville Avenue and later at Springfield Close. It would seem that confusion reigned. The Metropolitan thought they retained a tenancy of the land. However, because it was not needed during the First World War it had been sublet by the Metropolitan to Mr Sansom of Croxley Hall Farm. In addition, Rickmansworth Urban District Council (RUDC) had made an outright purchase of the Gonville Avenue site. There were many delays and legal decisions until the issue of the ownership was settled. On one occasion the Metropolitan tried to seize the land and put barriers up preventing access to RUDC. Gonville and Caius, also party to the dispute, accepted there had been a misunderstanding and the matter was settled amicably.

A temporary level crossing was introduced at the lower part of Baldwins Lane and Cassio Bridge. The line continued over the canal, skirting the fishing lake and watercress beds, crossing the River Gade and reaching what is now known as Gade Avenue. Some references cite this section as then being the lower part of Rousebarn Lane. An incline some distance further led to an engine shed and site maintenance depot. It is difficult now to imagine the area without building development. However, the only building of any significance was the John Dickinson mill situated on Common Moor.

Albert Freeman, the Rickmansworth Urban District surveyor had many confrontations with the company. Apparently, in the early planning stages the Metropolitan had taken tenancy of various sites in the area around the station. In particular, sites at Gonville Avenue and later at Springfield Close. It would seem that confusion reigned. The Metropolitan thought they retained a tenancy of the land. However, because it was not needed during the First World War it had been sublet by the Metropolitan to Mr Sansom of Croxley Hall Farm. In addition, Rickmansworth Urban District Council (RUDC) had made an outright purchase of the Gonville Avenue site. There were many delays and legal decisions until the issue of the ownership was settled. On one occasion the Metropolitan tried to seize the land and put barriers up preventing access to RUDC. Gonville and Caius, also party to the dispute, accepted there had been a misunderstanding and the matter was settled amicably.

A temporary level crossing was introduced at the lower part of Baldwins Lane and Cassio Bridge. The line continued over the canal, skirting the fishing lake and watercress beds, crossing the River Gade and reaching what is now known as Gade Avenue. Some references cite this section as then being the lower part of Rousebarn Lane. An incline some distance further led to an engine shed and site maintenance depot. It is difficult now to imagine the area without building development. However, the only building of any significance was the John Dickinson mill situated on Common Moor.

The principal items of plant eventually began to appear on the site and included four 0-6-0 cylinder saddle tank locomotives. These had no cabs for the drivers. There were just glass windows set in an upright weatherboard. Three steam cranes of various sizes for lifting were used. A string of wooden trucks enabled the transport of earth and other material. Some of the trucks were side tippers and others end tippers. The trucks had no springs or buffers and were loose coupled by use of chains slung between the frames. The extensive earthworks necessitated the use of three steam navvies or bucket cranes. These large machines were each expected to remove some half a million cubic yards of soil. They moved under their own power, running on two metal rails each 12 feet apart and laid on wooden sleepers. Each crane had a large jib which was capable of supporting a steel bucket containing 2 cwt (hundred weights) of spoil. Power for lifting and traction was powered by steam driven machinery. The boiler and main mechanism was housed in what was in effect a corrugated iron shed, the roof of which gave rise to a small chimney. The whole construction which could turn a half circle was supported on a bracket which in turn was fixed to a self- propelled truck. In operation, a screw jack was secured in each corner ensuring extra stability and consequently maximum efficiency. The process involved scraping the heavy bucket up the side of the cutting, thereby removing and catching the spoil which was then deposited into waiting trucks. The spoil was then hauled away to be used in creating embankments elsewhere. To complete some of the deeper cuttings it was necessary to make three passes because it was not safe to dig more than 15ft down at any one time.

In 1924 there was a delay of eight months because of difficult conditions on the north curve. This problem was near the Cassio Bridge site. On the Watford side of the Gade River behind the Boys’ school a gently sloping meadow ran down to the river. The site of the intended station had been a dell, into which had been tipped all kinds of scrap metal from World War 1-shell cases that had been made at the mill and carbon rods in abundance. There was an old aircraft hangar and various other relics of war. The boys’ school was nearby and it was only to be expected that there would be some curiosity and interest from that source.

At 9.30am on Saturday 10th November 1924 a party of senior boys from the school met at the top of Shepherd’s Road. They were going to visit the works led by Mr Merrett and Mr J P Porter, a representative of Messrs Logan and Hemmingway (who had kindly given permission for the visit) They proceeded to the railway engineer’s office to view several fossils, minerals and bones that had been found during the excavations.

The party then made their way towards the River Gade where they saw a forge, a repair workshop, engine sheds and water softening apparatus. Near the new embankment they came across a Sarsen stone, probably a relic of the last ice age. The stone was as large as a garden roller and was so hard it defied all efforts to break it with a geological hammer. The boys were doubtless fascinated to view the scene of activity on the banks of the River Gade.

To keep the excavations clear of percolating water from the river, two pumps, each capable of pumping water at the rate of seven hundred gallons an hour -were employed. On one side of the river they watched work on the construction of a large caisson being built to keep water back while foundations were laid. Under its own weight the caisson was expected to sink through thirty feet or so of rotten fragmented chalk. Outside the caisson the depth of gravel allowed the foundations to be carried upon 28 driven piles. These piles which were 45ft long were pine soaked in pitch to act as a preservative. They were driven into the ground by a steam driven pile driver. The complexities of a railway engineer’s job were impressed upon the boys along with the importance of a full appreciation of the terrain to be crossed.

The boys were encouraged to break open two large stones which they had collected. Crystals of quartz were revealed. These crystals were placed in the school museum.

The boys then made their way over temporary bridges where they were shown a mechanical concrete mixer. Eight parts of sand and gravel to one part of cement were mixed with water in a revolving hopper which had combs projecting inwards. When ready, the resulting concrete was tipped into a bucket to be carried by crane to the arches which were under construction.

They crossed the canal by a temporary girder bridge towards an embankment nearing completion. Here the boys were given the explanation of the need for height. Their trip ended at the site of the new Croxley Green station and Goods yard. The journey had taken them 2 ½hrs. Apparently they were disappointed not to have been able to enter the cuttings leading to Croxley Hall woods. Even though they had come from the high embankment and down to the cutting section they were in fact only 1ft higher than the site at the Watford Station. Walking back along the line they frequently had to stand clear as one or other of the tank engines dashed by with trucks transferring spoil from the cutting.

Six months on, Saturday May 2nd 1925 the boys made another visit. They met at Croxley Green station. Walking along the line in the London direction they were able to watch the construction of a short cut and cover tunnel, which was necessary to avoid the difficulty of building a 30ft “skewed” road bridge. The boys had a go at bricklaying. This cut and cover feature can just be seen through the woods close to Croxley Hall farm. Running down one side of a cutting was the root of a thistle which could be traced to its very end, some 40ft below the surface.

At Croxley Green Station they were shown a cabin under construction which would eventually house the latest type of automatic electric signalling system. It was also intended to have a Goods yard that would allow coal to be stored as well as other commodities for local distribution.

In 1924 there was a delay of eight months because of difficult conditions on the north curve. This problem was near the Cassio Bridge site. On the Watford side of the Gade River behind the Boys’ school a gently sloping meadow ran down to the river. The site of the intended station had been a dell, into which had been tipped all kinds of scrap metal from World War 1-shell cases that had been made at the mill and carbon rods in abundance. There was an old aircraft hangar and various other relics of war. The boys’ school was nearby and it was only to be expected that there would be some curiosity and interest from that source.

At 9.30am on Saturday 10th November 1924 a party of senior boys from the school met at the top of Shepherd’s Road. They were going to visit the works led by Mr Merrett and Mr J P Porter, a representative of Messrs Logan and Hemmingway (who had kindly given permission for the visit) They proceeded to the railway engineer’s office to view several fossils, minerals and bones that had been found during the excavations.

The party then made their way towards the River Gade where they saw a forge, a repair workshop, engine sheds and water softening apparatus. Near the new embankment they came across a Sarsen stone, probably a relic of the last ice age. The stone was as large as a garden roller and was so hard it defied all efforts to break it with a geological hammer. The boys were doubtless fascinated to view the scene of activity on the banks of the River Gade.

To keep the excavations clear of percolating water from the river, two pumps, each capable of pumping water at the rate of seven hundred gallons an hour -were employed. On one side of the river they watched work on the construction of a large caisson being built to keep water back while foundations were laid. Under its own weight the caisson was expected to sink through thirty feet or so of rotten fragmented chalk. Outside the caisson the depth of gravel allowed the foundations to be carried upon 28 driven piles. These piles which were 45ft long were pine soaked in pitch to act as a preservative. They were driven into the ground by a steam driven pile driver. The complexities of a railway engineer’s job were impressed upon the boys along with the importance of a full appreciation of the terrain to be crossed.

The boys were encouraged to break open two large stones which they had collected. Crystals of quartz were revealed. These crystals were placed in the school museum.

The boys then made their way over temporary bridges where they were shown a mechanical concrete mixer. Eight parts of sand and gravel to one part of cement were mixed with water in a revolving hopper which had combs projecting inwards. When ready, the resulting concrete was tipped into a bucket to be carried by crane to the arches which were under construction.

They crossed the canal by a temporary girder bridge towards an embankment nearing completion. Here the boys were given the explanation of the need for height. Their trip ended at the site of the new Croxley Green station and Goods yard. The journey had taken them 2 ½hrs. Apparently they were disappointed not to have been able to enter the cuttings leading to Croxley Hall woods. Even though they had come from the high embankment and down to the cutting section they were in fact only 1ft higher than the site at the Watford Station. Walking back along the line they frequently had to stand clear as one or other of the tank engines dashed by with trucks transferring spoil from the cutting.

Six months on, Saturday May 2nd 1925 the boys made another visit. They met at Croxley Green station. Walking along the line in the London direction they were able to watch the construction of a short cut and cover tunnel, which was necessary to avoid the difficulty of building a 30ft “skewed” road bridge. The boys had a go at bricklaying. This cut and cover feature can just be seen through the woods close to Croxley Hall farm. Running down one side of a cutting was the root of a thistle which could be traced to its very end, some 40ft below the surface.

At Croxley Green Station they were shown a cabin under construction which would eventually house the latest type of automatic electric signalling system. It was also intended to have a Goods yard that would allow coal to be stored as well as other commodities for local distribution.

Croxley Green before it was consumed by housing

Croxley Green before it was consumed by housing

A west curve in the line was laid to enable trains to run to and from Rickmansworth and stations to the north but its use diminished after 1934.

The Watford Station platform was 615ft long, 30ft wide and capable of handling a full –length main line passenger steam train. It had a 280ft wood and glass canopy. The station also had a Goods yard equipped with a large storage shed, a 5-ton crane, a carriage dock and cattle pens. The Watford Town Council insisted that all related vehicular traffic should use the new 40ft wide approach road from the main Rickmansworth Road thereby avoiding Cassiobury Park Avenue and other residential roads on the new estate.

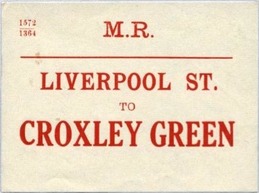

In 1925 management of the new branch was the responsibility of the Watford Joint Railway Committee. The two stations opened on 2nd November 1925. Most trains were worked by the Metropolitan. Others were worked by the London and North Eastern Railway making this a joint venture. There were 140 train movements every weekday. The Watford Goods yards were equipped to take inward and outward goods, minerals and livestock. A direct link now existed with towns and coalfields in the Midlands and North of England. This would directly benefit local industry. The total cost of the venture was in the region of £300.000. In November 1927 - a motor bus service was set up from Watford Station to the town centre. The fare was 1d (pre-decimal). Housing development in the area around and near Watford Station was yet to materialize.

The Watford Station platform was 615ft long, 30ft wide and capable of handling a full –length main line passenger steam train. It had a 280ft wood and glass canopy. The station also had a Goods yard equipped with a large storage shed, a 5-ton crane, a carriage dock and cattle pens. The Watford Town Council insisted that all related vehicular traffic should use the new 40ft wide approach road from the main Rickmansworth Road thereby avoiding Cassiobury Park Avenue and other residential roads on the new estate.

In 1925 management of the new branch was the responsibility of the Watford Joint Railway Committee. The two stations opened on 2nd November 1925. Most trains were worked by the Metropolitan. Others were worked by the London and North Eastern Railway making this a joint venture. There were 140 train movements every weekday. The Watford Goods yards were equipped to take inward and outward goods, minerals and livestock. A direct link now existed with towns and coalfields in the Midlands and North of England. This would directly benefit local industry. The total cost of the venture was in the region of £300.000. In November 1927 - a motor bus service was set up from Watford Station to the town centre. The fare was 1d (pre-decimal). Housing development in the area around and near Watford Station was yet to materialize.

In 1927 a Metropolitan Railway engineer who had been a resident engineer during the construction of the branch became aware and made it known to the Board that the premises Empress Tea Rooms at 44 High Street Watford with 2¼ acres of land extending back to Cassio Road were for sale. It was considered that there was enough space for a small passenger terminus and there were two possible approach routes. This was given due consideration and in October 1927, deemed to be a wise investment, the land was purchased through a third party. Nothing actually came of this although the shop was leased for a short time to a furniture retailer, thereby ensuring it could be re-possessed without any difficulties. The property was sold again the following year.

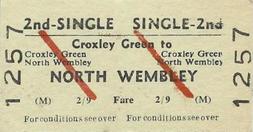

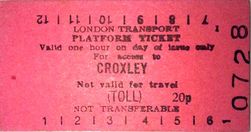

Soon afterwards there was a rapid development of land in the Croxley Green & Cassiobury areas. There was a huge advertising campaign to include these areas in what was becoming known as “Metroland”. The Met passed into the ownership of the London Transport Passenger Board on 1st July 1933. Having two stations both named Croxley Green obviously caused confusion. In May 1949 this was resolved when the second station to be built was renamed Croxley.

Soon afterwards there was a rapid development of land in the Croxley Green & Cassiobury areas. There was a huge advertising campaign to include these areas in what was becoming known as “Metroland”. The Met passed into the ownership of the London Transport Passenger Board on 1st July 1933. Having two stations both named Croxley Green obviously caused confusion. In May 1949 this was resolved when the second station to be built was renamed Croxley.

|

Sources

Watford Grammar School Fullerian 1924 &1925 ( Mrs Shirley Greenman) Chiltern Railways Remembered – Leslie Oppitz The Railways of Hertfordshire – F G Cockman West of Watford – F W Gouldie and Douglas Stuckey Metro Memoirs of Ron Pigram /Dennis Edwards Croxley Green Resident No 75 April 1962 (view issue HERE) The Book of Watford –Bob Nunn ( London’s Metropolitan Railway- Alan A Jackson) Hertfordshire Countryside magazine May 1971 Dictionary of British History – J P Keyon The Met & GC Joint Line – Clive Foxel |