A Country at War - We did our bit!

First World War

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in June 1914 triggered the massive international conflict which came to be known as World War One. The effects of this horrendous period influenced and directly affected the population of cities, towns and villages in many countries. Croxley Green together with all areas of Great Britain provided recruits and volunteers and worked together with a patriotic fervour to support the war effort. Not only did many local men leave their homes and families to take part in bitter and brutal fighting overseas but members of both sexes who stayed behind set to taking on unfamiliar tasks to ensure that, as far as possible, normality and social cohesion was maintained. Very soon, as was the case in communities throughout the United Kingdom, many familiar faces, particularly of its male population disappeared. Sadly and tragically a large number were never to return. The armed forces of the Crown needed manpower in vast numbers. Fathers, sons and brothers left to answer the call. It was not unusual for groups formed in civilian life to ‘join up’ together. A number of young members of Croxley Church Lads Brigade enlisted in the Kings Royal Rifle Corps.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in June 1914 triggered the massive international conflict which came to be known as World War One. The effects of this horrendous period influenced and directly affected the population of cities, towns and villages in many countries. Croxley Green together with all areas of Great Britain provided recruits and volunteers and worked together with a patriotic fervour to support the war effort. Not only did many local men leave their homes and families to take part in bitter and brutal fighting overseas but members of both sexes who stayed behind set to taking on unfamiliar tasks to ensure that, as far as possible, normality and social cohesion was maintained. Very soon, as was the case in communities throughout the United Kingdom, many familiar faces, particularly of its male population disappeared. Sadly and tragically a large number were never to return. The armed forces of the Crown needed manpower in vast numbers. Fathers, sons and brothers left to answer the call. It was not unusual for groups formed in civilian life to ‘join up’ together. A number of young members of Croxley Church Lads Brigade enlisted in the Kings Royal Rifle Corps.

An army unit camped on The Green in transit

An army unit camped on The Green in transit

Large troop movements became a common fact of life. The area around Rickmansworth became a staging point, much of the land being used for this purpose. Rickmansworth Park (now the Royal Masonic School for Girls’) was found to be ideal. On occasions The Green was used to bivouac hundreds of soldiers. Various regiments passed through including the Royal Artillery, the Royal Horse Guards and members of the Territorial Army. Residents were required to open their homes as ‘billet’ accommodation.

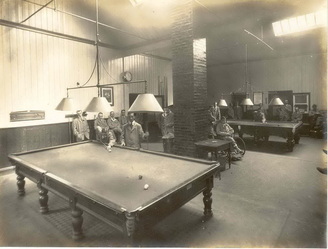

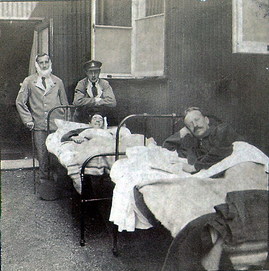

In October 1915 the Dickinson Institute was identified as suitable for conversion into a convalescent home for wounded soldiers. Albert Freeman the District Surveyor for Rickmansworth Urban District Council liaised with Charles Barton-Smith, the manager of Dickinson’s Paper Mill, regarding the necessary building works, plumbing etc. which were put in hand. The Institute became a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD). Nationally the VAD, founded in 1909 and incorporating the Red Cross and the Order of St John provided a voluntary auxiliary nursing organisation. As the wounded began to arrive many local women, including Barton-Smith’s daughter May, assisted in the provision of care. Recuperating soldiers were often seen in wheelchairs or pony carts on The Green enjoying the tranquillity and taking the air.

Mr. Foster, a local farmer who had milking sheds next to the VAD hospital, was asked to ensure the regular removal of manure in order to reduce the prevailing aroma.

In October 1915 the Dickinson Institute was identified as suitable for conversion into a convalescent home for wounded soldiers. Albert Freeman the District Surveyor for Rickmansworth Urban District Council liaised with Charles Barton-Smith, the manager of Dickinson’s Paper Mill, regarding the necessary building works, plumbing etc. which were put in hand. The Institute became a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD). Nationally the VAD, founded in 1909 and incorporating the Red Cross and the Order of St John provided a voluntary auxiliary nursing organisation. As the wounded began to arrive many local women, including Barton-Smith’s daughter May, assisted in the provision of care. Recuperating soldiers were often seen in wheelchairs or pony carts on The Green enjoying the tranquillity and taking the air.

Mr. Foster, a local farmer who had milking sheds next to the VAD hospital, was asked to ensure the regular removal of manure in order to reduce the prevailing aroma.

Various school activities had been held in the Institute and these returned to the individual school premises. At Christmas time, it was customary for the boys’ school to make their own amusement. They made a stage and presented various forms of entertainment. This social event was very popular and invitations were sent to the wounded soldiers at the VAD hospital. The boys encouraged them to join in the community singing.

A school garden was started; trenches were dug to enable the cultivation of an area in readiness for the growing of vegetables. The aim was to send the produce to the VAD hospital thereby providing fresh vegetables for the wounded patients. The boys were particularly pleased to be able to ensure there were brussel sprouts for the Christmas dinner each year. A record was kept of the quantity of vegetables grown. Following one particular harvest 15cwt of potatoes and in total 130lbs of beans, turnips, onions, pumpkins, marrows, carrots and sprouts were sent to the hospital.

Neggy Wilson, the headmaster, was particularly proud when he was informed that several ‘old boys’ had been awarded the Military Medal for bravery. The school also gave concerts in the large school room to raise money for the Red Cross funds.

However, the relationship between the boys’ school and the VAD hospital did not always run smoothly. At play time and after school the proximity of the school and the hospital meant that the noisy exuberance of the pupils disturbed the peace and tranquility so essential to successful convalescence. A meeting was held between the two organisations and the immediate vicinity of the hospital became out of bounds to the boys. A pupils’ committee resolved to ‘police’ the agreement. A notice outlining this resolution was sent to the parents in the village of boys between the ages of 14-17 seeking their co-operation. The school log book records that the committee ‘met and tried two boys’ who had been playing during the evening in the vicinity of the hospital. The hospital was informed and the school received a letter from the commandant thanking the school for dealing with the matter. The report made no mention of the punishment.

The older girls now spent the whole of their school life in the original (but now much extended) school and after almost 40 years of teaching at the school, Miss Aricie Clarke retired as Headmistress at the end of term in July 1915.

Miss Mildred May Stanford became the new Headmistress in September transferring from the Old Boys School. She began as an assistant teacher at the age of twenty under H T Wilson. Originally from Abridge a small village in Essex and educated at Chigwell Grammar School, she dedicated her career not only to teaching her pupils academic subjects but also to encouraging social opportunities

During these disturbing times, the children became aware of the suffering that the Belgian children were experiencing. They were encouraged to help with financial aid and collections of money were sent at Christmas time.

The enemy destroyed British shipping, thereby adversely affecting imports of food supplies, so it became vital to increase production at home.

As in so many other tasks hitherto undertaken by men, women now became involved in agriculture. The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was formed and its members undertook every conceivable type of farm work, from herding and milking cows to ploughing by horse, harvesting and even thatching.

A school garden was started; trenches were dug to enable the cultivation of an area in readiness for the growing of vegetables. The aim was to send the produce to the VAD hospital thereby providing fresh vegetables for the wounded patients. The boys were particularly pleased to be able to ensure there were brussel sprouts for the Christmas dinner each year. A record was kept of the quantity of vegetables grown. Following one particular harvest 15cwt of potatoes and in total 130lbs of beans, turnips, onions, pumpkins, marrows, carrots and sprouts were sent to the hospital.

Neggy Wilson, the headmaster, was particularly proud when he was informed that several ‘old boys’ had been awarded the Military Medal for bravery. The school also gave concerts in the large school room to raise money for the Red Cross funds.

However, the relationship between the boys’ school and the VAD hospital did not always run smoothly. At play time and after school the proximity of the school and the hospital meant that the noisy exuberance of the pupils disturbed the peace and tranquility so essential to successful convalescence. A meeting was held between the two organisations and the immediate vicinity of the hospital became out of bounds to the boys. A pupils’ committee resolved to ‘police’ the agreement. A notice outlining this resolution was sent to the parents in the village of boys between the ages of 14-17 seeking their co-operation. The school log book records that the committee ‘met and tried two boys’ who had been playing during the evening in the vicinity of the hospital. The hospital was informed and the school received a letter from the commandant thanking the school for dealing with the matter. The report made no mention of the punishment.

The older girls now spent the whole of their school life in the original (but now much extended) school and after almost 40 years of teaching at the school, Miss Aricie Clarke retired as Headmistress at the end of term in July 1915.

Miss Mildred May Stanford became the new Headmistress in September transferring from the Old Boys School. She began as an assistant teacher at the age of twenty under H T Wilson. Originally from Abridge a small village in Essex and educated at Chigwell Grammar School, she dedicated her career not only to teaching her pupils academic subjects but also to encouraging social opportunities

During these disturbing times, the children became aware of the suffering that the Belgian children were experiencing. They were encouraged to help with financial aid and collections of money were sent at Christmas time.

The enemy destroyed British shipping, thereby adversely affecting imports of food supplies, so it became vital to increase production at home.

As in so many other tasks hitherto undertaken by men, women now became involved in agriculture. The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was formed and its members undertook every conceivable type of farm work, from herding and milking cows to ploughing by horse, harvesting and even thatching.

WW1 local land army girls

WW1 local land army girls

Albert Freeman, became responsible locally for ensuring on behalf of the government the provision of ‘anything connected to the war’. This was in addition to carrying out his normal work.

Street lighting was banned as were shop lights from dusk. Police officers and soldiers were tasked with obtaining trolleys to form barricades at strategic points in the area. Scotsbridge and the Sarratt Road near Croxley House were sites included and soldiers were positioned to stop and search vehicles. As agreed between Albert Freeman and the Board of Agriculture many locations were identified, commandeered and given over to food production. The grounds of Croxley House, football pitches, meadows and allotments came under the plough. Local production got underway when the then Watford Urban District Council obtained a large supply of seed potatoes which arrived at the LMS sidings. The potatoes were bagged, labelled and carted to Rickmansworth for distribution subject to the approval of a formal application.

There was a shortage of coal and consequently fuel rationing. Rationing became part of life, ensuring as far as possible the fair distribution of necessities.

Zeppelin airships appeared in the skies locally from time to time and air raid warning became frequent occurrences. Enemy aircraft were seen to be shot down. As the conflict progressed British soldiers captured many German troops. These prisoners were brought to Britain and the need arose to provide them with secure accommodation and put them to useful work. Initially many were taken to Halton Park in Wendover, Bucks. It was from there that they were transferred to suitable locations elsewhere. Albert Freeman ensured adequate provision was made in the Rickmansworth area. Rickmansworth Park proved ideal for the purpose and the stabling there was converted accordingly. The prisoners took up residence and were soon to be seen working on local farms.

Refugees seeking asylum began arriving from Europe. Local people did what they could to make them welcome, some lending furniture and other household requirements.

Of the young men who had gone off as volunteers to fight many were killed early on in the conflict. As these deaths occurred and the news was received their names were read out during church services. On All Souls Day, 2nd November 1916, a memorial service was held and the names of seventeen young soldiers were remembered.

Street lighting was banned as were shop lights from dusk. Police officers and soldiers were tasked with obtaining trolleys to form barricades at strategic points in the area. Scotsbridge and the Sarratt Road near Croxley House were sites included and soldiers were positioned to stop and search vehicles. As agreed between Albert Freeman and the Board of Agriculture many locations were identified, commandeered and given over to food production. The grounds of Croxley House, football pitches, meadows and allotments came under the plough. Local production got underway when the then Watford Urban District Council obtained a large supply of seed potatoes which arrived at the LMS sidings. The potatoes were bagged, labelled and carted to Rickmansworth for distribution subject to the approval of a formal application.

There was a shortage of coal and consequently fuel rationing. Rationing became part of life, ensuring as far as possible the fair distribution of necessities.

Zeppelin airships appeared in the skies locally from time to time and air raid warning became frequent occurrences. Enemy aircraft were seen to be shot down. As the conflict progressed British soldiers captured many German troops. These prisoners were brought to Britain and the need arose to provide them with secure accommodation and put them to useful work. Initially many were taken to Halton Park in Wendover, Bucks. It was from there that they were transferred to suitable locations elsewhere. Albert Freeman ensured adequate provision was made in the Rickmansworth area. Rickmansworth Park proved ideal for the purpose and the stabling there was converted accordingly. The prisoners took up residence and were soon to be seen working on local farms.

Refugees seeking asylum began arriving from Europe. Local people did what they could to make them welcome, some lending furniture and other household requirements.

Of the young men who had gone off as volunteers to fight many were killed early on in the conflict. As these deaths occurred and the news was received their names were read out during church services. On All Souls Day, 2nd November 1916, a memorial service was held and the names of seventeen young soldiers were remembered.

All Saints Rememberance board WW1

All Saints Rememberance board WW1

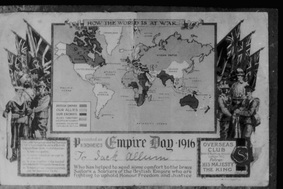

Empire Day was first celebrated on 24th May 1902, Queen Victoria’s birthday and continued throughout the war. Croxley Green log books record that local school children had a day off school to celebrate this day. Several of the older girls were selected to represent countries of the British Empire and dress in their national costume. The schools would come together and salute the Union Jack flag, sing patriotic songs including “God Save the King” as well as hear inspirational speeches.

In 1910 a movement was formed by Sir John Evelyn Wrench with the ethos to promote children from an early age to act with “Responsibility, Sympathy, Duty, and Self-sacrifice.”

With the outbreak of war he set up the Empire Fund as part of the Overseas Club to appeal to children to give their pennies for the troops’ tobacco and home comforts. Children were rewarded with certificates on Empire Day. Jack Allum was one of the village children who received this award in 1916.

By 1918 it became necessary to increase the size of the Special Constabulary. Charles Barton-Smith became involved with the recruitment. The newly appointed constables were provided with suitable uniform caps which they were required to wear when on duty.

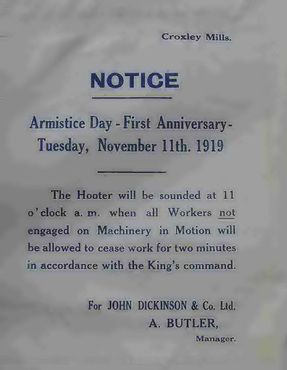

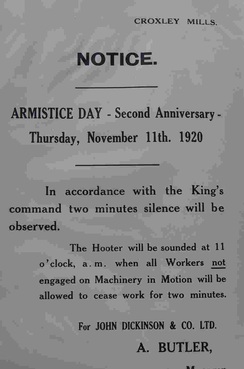

As the war drew to a close, severely wounded men, some of them blinded, began returning home. Local collections were made in order to give some monetary support to the families. It was recorded in the Boys School log book that several of the ‘old boys’ received the Military Medal for bravery. Germany formally surrendered at 11am on the 11th November 1918. News of this soon reached Croxley Green of the ‘Allies’ defeat of Germany and the sound of the church bells in Rickmansworth confirmed the end of the war. This gave rise to immediate celebration; Charles Barton–Smith insisted that the boys’ school flag be hoisted without delay. Giving spontaneous cheer, children of all ages together with their teachers processed from the school to the church. The National flags of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and India were displayed. The National Anthem was sung. The procession then made its way to the VAD hospital. There, the wounded soldiers were invited to express their feelings of the great news. The procession eventually made its way around Dickinson Square into the Watford Road to the Red House. They returned via New Road to the Square and along Dickinson Avenue back to the schools.

In 1910 a movement was formed by Sir John Evelyn Wrench with the ethos to promote children from an early age to act with “Responsibility, Sympathy, Duty, and Self-sacrifice.”

With the outbreak of war he set up the Empire Fund as part of the Overseas Club to appeal to children to give their pennies for the troops’ tobacco and home comforts. Children were rewarded with certificates on Empire Day. Jack Allum was one of the village children who received this award in 1916.

By 1918 it became necessary to increase the size of the Special Constabulary. Charles Barton-Smith became involved with the recruitment. The newly appointed constables were provided with suitable uniform caps which they were required to wear when on duty.

As the war drew to a close, severely wounded men, some of them blinded, began returning home. Local collections were made in order to give some monetary support to the families. It was recorded in the Boys School log book that several of the ‘old boys’ received the Military Medal for bravery. Germany formally surrendered at 11am on the 11th November 1918. News of this soon reached Croxley Green of the ‘Allies’ defeat of Germany and the sound of the church bells in Rickmansworth confirmed the end of the war. This gave rise to immediate celebration; Charles Barton–Smith insisted that the boys’ school flag be hoisted without delay. Giving spontaneous cheer, children of all ages together with their teachers processed from the school to the church. The National flags of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and India were displayed. The National Anthem was sung. The procession then made its way to the VAD hospital. There, the wounded soldiers were invited to express their feelings of the great news. The procession eventually made its way around Dickinson Square into the Watford Road to the Red House. They returned via New Road to the Square and along Dickinson Avenue back to the schools.

A certificate awarded to Jack Allum for his contribution

A certificate awarded to Jack Allum for his contribution

There was a feeling of relief often tinged with sadness at the loss of loved ones. Flags and bunting were displayed around the village, providing a fitting backdrop to the various celebrations that were to follow.

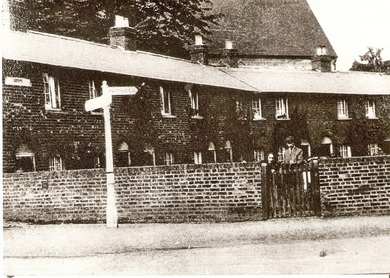

However, many localities and ways of life had changed dramatically. Women having to some extent achieved and filled roles previously undertaken by men were beginning to demand acknowledgement for their achievements. Some of the returning servicemen found difficulty in finding accommodation. House building had ceased during the war. New families were still coming to Croxley Green and many families were increasing in size. A row of cottages adjacent to All Saints Church had been identified as being below a satisfactory standard. These were known as the Berean Cottages. Although being considered as ‘not up to standard’ it was decided that they would provide adequate housing in the short term. The houses were soon renamed ‘Heroes Terrace or ‘Penny Row’, the weekly rent being just one penny and many accommodated ex service men.

However, many localities and ways of life had changed dramatically. Women having to some extent achieved and filled roles previously undertaken by men were beginning to demand acknowledgement for their achievements. Some of the returning servicemen found difficulty in finding accommodation. House building had ceased during the war. New families were still coming to Croxley Green and many families were increasing in size. A row of cottages adjacent to All Saints Church had been identified as being below a satisfactory standard. These were known as the Berean Cottages. Although being considered as ‘not up to standard’ it was decided that they would provide adequate housing in the short term. The houses were soon renamed ‘Heroes Terrace or ‘Penny Row’, the weekly rent being just one penny and many accommodated ex service men.

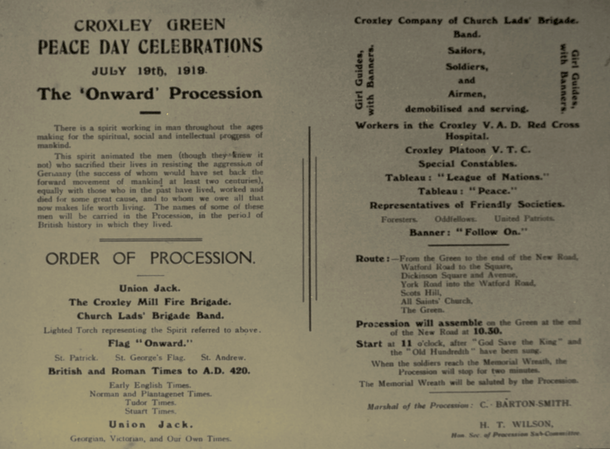

"On 28th June 1919, Great Britain with others countries signed the Peace Treaty at Versailles, France, finally bringing the WW1 conflict to a close. To celebrate this and to bring closure to the war, Saturday 19th July 1919 would be observed as a Public Holiday throughout Great Britain.

At that time, the village of Croxley Green organised a grand display and a parade to celebrate the occasion. As the village population had recently grown it was evident that it had become a close community."

At that time, the village of Croxley Green organised a grand display and a parade to celebrate the occasion. As the village population had recently grown it was evident that it had become a close community."

"Many Croxley Green groups played a part in the celebrations. There was a procession to The Green. Children dressed in the national colours of the various victorious countries and carried relevant national flags."

A tradition of planting oak trees on The Green to celebrate major events had started in the reign of Queen Victoria. Accordingly it was decided to commemorate the war dead. HT Wilson, Neggy, (Headmaster of the boys’ school), along with other residents selected a suitable oak tree from Berkhamstead. The villagers raised the money for the tree by purchasing special little lapel button badges. The tree was blessed at a special service in All Saints Church and then carried to the designated site on The Green. On Sunday afternoon 2nd November 1919 the tree was duly planted by ex-servicemen. Large granite blocks were obtained from the John Dickinson mill and placed together in front of the tree with the names of those who had lost their lives. Protective railings with a gate were erected to deter passing cattle from damaging the young tree. (At this time cows were still being herded daily from the fields near the Sarratt Road to a milking parlour on Scots Hill.)

A memorial service was held the following and subsequent years on 11th November 1920. Many Croxley Green groups played a part in the celebrations. There was a procession to The Green. Children dressed in the national colours of the various victorious countries and carried relevant national flags.

"A tradition of planting oak trees on The Green to celebrate major events had started in the reign of Queen Victoria. Accordingly it was decided to commemorate the war dead. HT Wilson, Neggy, (Headmaster of the boys’ school), along with other residents selected a suitable oak tree from Berkhamstead. The villagers raised the money for the tree by purchasing special little lapel button badges. The tree was blessed at a special service in All Saints Church and then carried to the designated site on The Green. On Sunday afternoon 2nd November 1919 the tree was duly planted by ex-servicemen. Large granite blocks were obtained from the John Dickinson mill and placed together in front of the tree with the names of those who had lost their lives. Protective railings with a gate were erected to deter passing cattle from damaging the young tree.

(At this time cows were still being herded daily from the fields near the Sarratt Road to a milking parlour on Scots Hill.)

(At this time cows were still being herded daily from the fields near the Sarratt Road to a milking parlour on Scots Hill.)

" A memorial service was held the following and subsequent years on 11th November 1920"

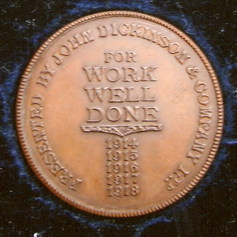

Side one of the medal presented to all of the staff

Side one of the medal presented to all of the staff

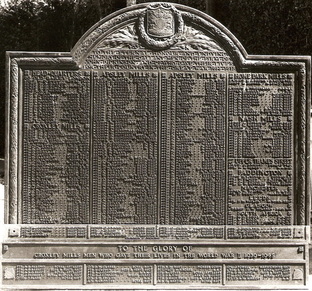

In early 1919 the records of John Dickinson showed the company also wished to commemorate the war by acknowledging the sacrifices employees had made – many had lost their lives. At a joint managers’ board meeting it was agreed that an identical bronze tablet be provided at all branches of the firm showing the names of all the fallen from the whole company. Each branch would be listed separately. Mr. Charles Barton- Smith represented the Croxley Mills at this meeting. The bronze tablet was designed and made in Edinburgh and produced by Mr. Charles Henshaw. Thirty eight men were named from Croxley Mill on this plaque initially mounted on the wall in the Dickinson Institute.

The dedication at the top reads “To the Eternal Honour and Undying memory of the gallant men of the Firm of John Dickinson and Company who gave their lives for their Country in the Great War 1914-1918.” A dedication at the base reads ‘Greater love hath no man than this’.

The finished plaque for Croxley Mill was received in October1921.

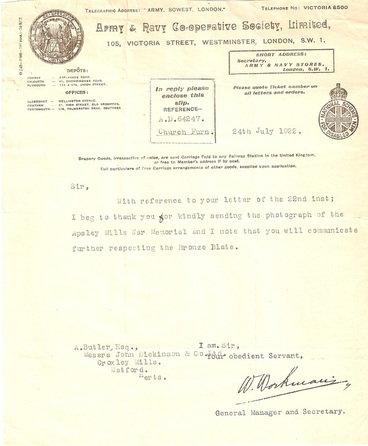

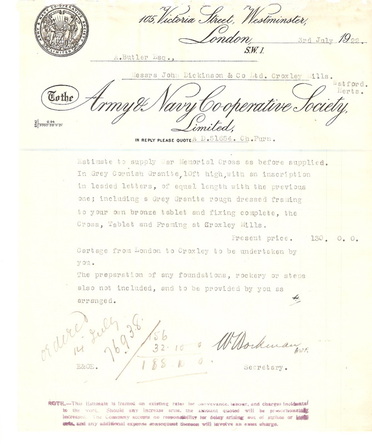

However, members of the workforce themselves decided they would like to have a memorial in the form of a Celtic cross made from Cornish granite and similar to the cross that had been proposed for the Apsley Mill site. A monetary collection took place but due to the economic slump after the war it failed to reach its intended target. John Dickinson stepped in and provided the necessary additional funds. A 10ft high Celtic cross was designed and supplied by the Army and Navy Co-operative Society Ltd. /Church Furniture and Memorials Dept.105, Victoria Street, Westminster, London SW1. The cross would have the same dedication at its base as that of the bronze tablet. A site was chosen for a memorial garden at the main Watford entrance to the mill and the Celtic cross was positioned on a turf bank faced with rough stone. It was also agreed the bronze tablet/plaque originally fitted in the Institute should be remounted in a block behind the Memorial Cross.

The dedication at the top reads “To the Eternal Honour and Undying memory of the gallant men of the Firm of John Dickinson and Company who gave their lives for their Country in the Great War 1914-1918.” A dedication at the base reads ‘Greater love hath no man than this’.

The finished plaque for Croxley Mill was received in October1921.

However, members of the workforce themselves decided they would like to have a memorial in the form of a Celtic cross made from Cornish granite and similar to the cross that had been proposed for the Apsley Mill site. A monetary collection took place but due to the economic slump after the war it failed to reach its intended target. John Dickinson stepped in and provided the necessary additional funds. A 10ft high Celtic cross was designed and supplied by the Army and Navy Co-operative Society Ltd. /Church Furniture and Memorials Dept.105, Victoria Street, Westminster, London SW1. The cross would have the same dedication at its base as that of the bronze tablet. A site was chosen for a memorial garden at the main Watford entrance to the mill and the Celtic cross was positioned on a turf bank faced with rough stone. It was also agreed the bronze tablet/plaque originally fitted in the Institute should be remounted in a block behind the Memorial Cross.

Side two of the medal presented to all the staff

Side two of the medal presented to all the staff

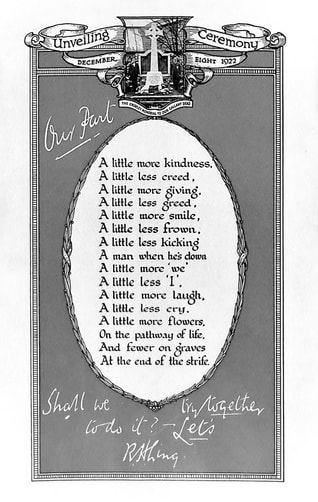

A large gathering of employees and representatives from Apsley Mill assembled for the memorial ceremony on December 8th 1922, as well as family members of those who had lost their lives. Members of the Mills Fire Brigade under First Officer A. Beck, Second Officer G Kerr and the Secretary, J Waller, were formed in a semi circle at the base and held wreaths for laying. Practically every department was represented including the Salle, Traffic, Rag, Finishing, Electrical, Office, Stationery, Engineering and many more. The Rev C.H. Blois Bisshopp, Vicar of All Saints Church, Mr. R.H. Ling, Managing Director, Mr. M Skeins, Manager of Croxley Mill, and Mr. Charles Barton-Smith, retired manager, were also present.

Ex-servicemen too attended, also representing various departments: Mr. J White (Engineers), Mr. G Chapman (Papermakers), Mr. J Stratford (Cutters), Mr. P Gardiner (Half -stuff), Mr. J Brown (Salle), Mr. J Hull (Stationery). The arrangements for this occasion was organised by a small committee with Mr. John Wilson as chairman and Mr. J. A. Asprey as organising secretary.

Ex-servicemen too attended, also representing various departments: Mr. J White (Engineers), Mr. G Chapman (Papermakers), Mr. J Stratford (Cutters), Mr. P Gardiner (Half -stuff), Mr. J Brown (Salle), Mr. J Hull (Stationery). The arrangements for this occasion was organised by a small committee with Mr. John Wilson as chairman and Mr. J. A. Asprey as organising secretary.

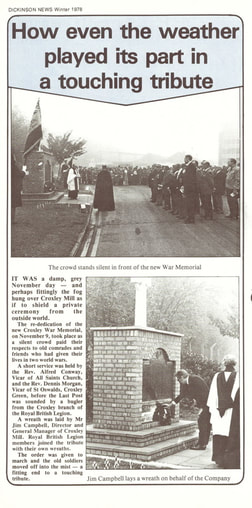

The memorial garden remained in this position for many years but during the building work that took place on the mill site during the 1960s it was necessary for it to be moved and unfortunately the Celtic cross was broken. The tablet however was re-housed in a simple brick structure and a replacement 5ft marble Celtic cross was purchased and mounted on top but carried no dedication. During the demolition of the Mill in the 1980s, as the whole site was being cleared, the Royal British Legion salvaged the bronze memorial tablet and the new marble Celtic cross. After lengthy discussions with All Saints Church the tablet was fixed to the south wall of the church and an area was made available in front as a ‘Garden of Remembrance’. A re-dedication service took place on Remembrance Sunday November 1985.

The grounds of the church did not allow for the replacement Celtic cross to be included and it was accepted at the time by a resident for safe keeping.

The grounds of the church did not allow for the replacement Celtic cross to be included and it was accepted at the time by a resident for safe keeping.