Julia Matheson - Memories of Croxley Green

Recorded 27th April 2022

Recorded 27th April 2022

Int: Can you just confirm your name and how long you’ve lived in Croxley.

JM: My name is Julia and I’ve lived in Croxley since about 1940, late 1940 I think.

Int: Right. OK. So you weren’t born in Croxley?

JM: No, I was born in London in 1938, so when my father went into the army when war was declared, he went very quickly, my mother decided with a very young child that it would be better to be outside London and wait for him to come back as we hoped then, so she came and rented a house in Repton Way to begin with and then for some reason came to this house in Yorke Road in April 1941- I actually have the rent book from that date because the landlady lived next door and we paid rent weekly.

Int: OK. So you were very young then - it was wartime. What are your earliest memories of Croxley and how it looked in the early 1940s, mid 1940s?

JM: Most of it of course in the central bits like Watford Road and New Road and Yorke Road and Dickinson Avenue and all that is very much as it used to be. Shops, of course, are different and Scots Hill has changed tremendously, and of course there is an awful lot of building that has gone on on the other side of Baldwin’s Lane, the whole area over there. But I think the main thing is really that there are so many more shops here.

Int: Right, yes. And presumably a lot more green spaces as well.

JM: No – well, I mean I wasn’t conscious of that because, you know, going for walks, and the Green was exactly as it was. The Croxley Hall Woods exactly as it was. Orchards – I mean the cherry orchard actually was a cherry orchard in those days and sold cherries. But I wouldn’t say there was any more green space.

Int: Right. Interesting. Well, the war. What do you remember of being here in war time?

JM: My name is Julia and I’ve lived in Croxley since about 1940, late 1940 I think.

Int: Right. OK. So you weren’t born in Croxley?

JM: No, I was born in London in 1938, so when my father went into the army when war was declared, he went very quickly, my mother decided with a very young child that it would be better to be outside London and wait for him to come back as we hoped then, so she came and rented a house in Repton Way to begin with and then for some reason came to this house in Yorke Road in April 1941- I actually have the rent book from that date because the landlady lived next door and we paid rent weekly.

Int: OK. So you were very young then - it was wartime. What are your earliest memories of Croxley and how it looked in the early 1940s, mid 1940s?

JM: Most of it of course in the central bits like Watford Road and New Road and Yorke Road and Dickinson Avenue and all that is very much as it used to be. Shops, of course, are different and Scots Hill has changed tremendously, and of course there is an awful lot of building that has gone on on the other side of Baldwin’s Lane, the whole area over there. But I think the main thing is really that there are so many more shops here.

Int: Right, yes. And presumably a lot more green spaces as well.

JM: No – well, I mean I wasn’t conscious of that because, you know, going for walks, and the Green was exactly as it was. The Croxley Hall Woods exactly as it was. Orchards – I mean the cherry orchard actually was a cherry orchard in those days and sold cherries. But I wouldn’t say there was any more green space.

Int: Right. Interesting. Well, the war. What do you remember of being here in war time?

JM: I remember vaguely tanks going down Watford Road and the way that the treads of the tanks damaged the surface of the road, and obviously I remember the black out, and I remember one of the bombs falling, because that blew our front door off the hinges. I can’t remember it actually breaking the windows, but then possibly they were taped up, I can’t remember. And I also very much remember that we tended to live in one room because it was cold and it was easier to keep on room heated and comfortable, so we didn’t live all over the house and we had a bed under the stairs, there is a sort of - intended I think to be the larder or something, but anyway my mother managed to shove a single bed in there and we used to sleep in there – she had a light put in – to be safe. And in this one room where we lived and we had the radio – wireless as it of course was in those days - and an open fire, and one night the chimney caught fire and I can remember the air raid warden or the fire warden coming and saying “Put that out! Put that out! Put that out!” and my mother saying “I don’t know what to do, I don’t know how to do”. Because of course flames and sparks coming out at the top. So that was one vivid memory. And then I started off at school in Yorke Road Infants, but I was only there for a short while because at that time Watford Grammar had an elementary department so I went there before the end of the war, before I was seven, I was late six, and I remember very much a raid there because we were in Lady’s Close part of the Grammar School and we all went into the cellars, which was very exciting. So that was another very strong wartime memory. (https://www.croxleygreenhistory.co.uk/second-world-war-1939-1945.html)

And I remember sort of trailing round the shops, because of course with rationing you went – you were allotted certain shops but you could also register in different ones and with your coupons, and you would go round to different ones and getting different things if they happened to have them in.

Int: So when the air raid sirens went off here, wasn’t there an air raid siren on the windmill?

JM: Yes. Oh yes, I can remember the sound of that, and then the all clear. And I think my mother was very, very concerned that I shouldn’t be frightened, so it wasn’t made into

“Oh dear, oh dear, we’re going to be bombed!” It was “Oh look, there’s” you know, “there’s the air raid warning” and we would just go into the thing under the stairs. And I remember walking with her and you heard the sound of anti-aircraft guns, and again she made it more like a joke – so I didn’t know what anti-aircraft meant, but it was just a nice sound of words. So she was very careful in that way.

Int: Yes. It must have been very frightening for her.

JM: I think it must have, definitely. And of course I do remember vaguely the telegram arriving to say that my father had been killed. I can remember being in the hall and this little envelope and again, because I never knew him, it didn’t mean very much. But what it must have meant to her goodness knows. Because again I don’t remember her being upset in any particular way.

And I remember sort of trailing round the shops, because of course with rationing you went – you were allotted certain shops but you could also register in different ones and with your coupons, and you would go round to different ones and getting different things if they happened to have them in.

Int: So when the air raid sirens went off here, wasn’t there an air raid siren on the windmill?

JM: Yes. Oh yes, I can remember the sound of that, and then the all clear. And I think my mother was very, very concerned that I shouldn’t be frightened, so it wasn’t made into

“Oh dear, oh dear, we’re going to be bombed!” It was “Oh look, there’s” you know, “there’s the air raid warning” and we would just go into the thing under the stairs. And I remember walking with her and you heard the sound of anti-aircraft guns, and again she made it more like a joke – so I didn’t know what anti-aircraft meant, but it was just a nice sound of words. So she was very careful in that way.

Int: Yes. It must have been very frightening for her.

JM: I think it must have, definitely. And of course I do remember vaguely the telegram arriving to say that my father had been killed. I can remember being in the hall and this little envelope and again, because I never knew him, it didn’t mean very much. But what it must have meant to her goodness knows. Because again I don’t remember her being upset in any particular way.

Int: What year was that?

JM: 1942. But I mean he was gone – because I was born January 1938 and he went into training as soon as the war started, because – because of his age he knew he would be called up, so you know it looked better, shall we say, if he volunteered. So he did and so he went away very soon after the outbreak of the war because of the training before you actually went into the Forces. So I never saw him.

Int: And your mum found herself as a single mother.

JM: Oh absolutely, yes.

Int: Very early on in her life, really, and at a very difficult time (JM: Yes). Did she work?

JM: Well, she was a trained infants teacher, so what she did was set up a small nursery school – because I think you could only have – I can’t remember how many pupils – in the house, but because this house wasn’t arranged as a nursery school, even though things weren’t as strict then as they would be now, with what facilities you had, the fact that this was just an ordinary house … so she managed that. She got a war widow’s pension, which I think – I mean I don’t know when these sort of things started or quite – I mean I think my father must have sent something – whatever his army pay was must have come to her. But I mean she did work as a teacher in London before I was born. Then there was that period when I was too young for her to go out to work, but as soon as I was at school she went back to teaching, because as a teacher her hours were more or less the same as mine.

Int: So did your mum run the nursery school from here in the house?

JM: Yes. So if it was raining it was in this room, actually, and she would have little tables and chairs and things, and if it was fine we were in the garden. Because this was literally, you know a nursery school, so these were pre-school children.

Int: Including you.

JM: Including me, absolutely, yes!

Int: And when you were a little bit older, then, how did you entertain yourself? What did you do when you weren’t at school?

JM: Well, I had school friends and we would play in the road, which, you know, is inconceivable now, and we would have skipping and things like that. And then listening to the wireless and reading and my mother read to me before I was doing much reading for myself, so books were always part of my life.

Int: Do you remember your favourite books when you were growing up, as a little girl?

JM: Gosh. I think Dr Dolittle, things like that. I mean she was very concerned we got all the sort of classic children’s books, Mary Poppins and Mary Plain – I don’t know if you remember those, about the bear in the bear pits of Berne.

Int: No I don’t remember those.

JM: So there was those and Millions of Cats, which I absolutely loved, because I’ve always liked cats, and that started when I was very young. I think that’s about it, really, that I can think of particularly. Arthur Ransome of course. All the expected ones for children in the 1940s, so the things that were popular in the 1930s or written in the 1930s.

Int: So, going back to shopping, you said you used to trail round with the ration book and everything when you were – well, becoming a teenager then – can you remember at the end of the 1940s early 1950s where most of the shops were around here that you used to go to?

JM: Well, by then we were probably be going to Rickmansworth. At the top of Scots Hill there was a very good grocer’s, there was the greengrocer there as well, and then there was Luxton’s the newsagent. There was Window’s the haberdashery, the little haberdashery shop, which was lovely, and there was bicycle shop I can vaguely remember there. And then in New Road there were the butchers, there were – I think there were two grocers, another greengrocer. There were butchers in Watford Road and various other shops there, but somehow or other I never associate going much to the Watford Road shops, it was always New Road or Scots Hill, and then to Rickmansworth, because the library was in Rickmansworth, and I can remember going to the children’s library there, which was sort of near where Watersmeet is now, and I can remember – it was a wooden building and I can absolutely remember the smell of it, but it was such a good library, really excellent. Also the fishmonger was in Rickmansworth, there was no fishmonger in Croxley, so you would have to go there. And there were two cinemas in Rickmansworth then, so occasionally we would go to the cinema. Sometimes we would walk but more often get the bus, because there were so many more buses – I mean you’d just walk round to the bus stop and get the bus down to Ricky.

Int: Where did the buses stop in New Road?

JM: Well, yes but we would go to the bus stop where – I mean the bus stops haven’t changed, so from this house one would go to the bus stop near the church, it’s nearer.

Int: So you’re becoming a teenager and – what, in ‘51? And obviously throughout the fifties, what are your memories of that sort of time. Did Croxley change very much in those postwar years?

JM: I don’t know, really. I suppose not. There again, because I went to school in Watford, this is my problem when people ask me about Croxley. I was in school in Watford, I went to university in London, and I worked in London, so I don’t actually have a whole lot of connections with Croxley, really. When I was in university, I lived in London, so I didn’t come home much then. So after my childhood, really, I don’t have much memory of Croxley as such, or being terribly aware of things changing or what was going on.

Int: Of course the station was there, so it was very convenient.

JM: Oh yes, absolutely, and we used to go to London a lot, because my mother liked London and had lived in London before she was married and during her early married life, and she was very keen on the theatre, so we would go to the theatre a lot. And even during the war we went to matinees, various foreign companies for some reason came – I can’t remember whether it was literally during wartime but I think it was. So we would go to a matinee which was safe or as safe as anything, and then we would go to the theatre a lot.

Int: On the Met Line.

JM: On the Met Line. The nice old brown trains. And I mean sometimes there were things like workmen’s trains – you could get cheap fares – I think maybe before 8 o’clock or even earlier than that – and we would do that and it was a way of saving money and it meant you had a jolly long day in London.

Int: Can you remember how much it cost to go to London?

JM: No, because I didn’t pay! But I mean it wasn’t very much. Now with Oyster cards you aren’t aware of how much it costs and that’s the terrible thing.

Int: Did you have any jobs growing, maybe in Croxley?

JM: I used to do a paper round, from school, that was ten shillings a week, I remember. That was from Luxton’s, and I did Watford Road and Bateman Road mostly. But I shared the round with a school friend who lived down in Watford Road. We would do one week on and one week off and when it was my week off if someone had let him down he would telephone and say could I come in, and so I would have to go in and do a spare round.

Int: And that was delivering the newspaper before you went to school?

JM: Oh yes, absolutely, because people had to have their newspapers early so you know – because I would need to get a bus from here to go to school probably soonish after 8, so you’d go, you know, half past six to do the paper round.

Int: Did you go on a bicycle (JM: Yes) or walking?

JM: No, I’d bicycle, and with an extraordinarily heavy bag of newspapers when I started and he did have some bikes with the basket in front, but I never had one of those, I always used to use my own bike. But it was quite heavy going. And I also – just more for fun really, because milk was delivered in a horse and cart in the early days and I was crazy about horses, very little girl and ponies kind of thing, so at the weekend, this was not a thing I could do during the week, definitely, I used to walk down through the woods to meet him, because the Poulter’s Dairy stables were in Ricky, and he would load up his cart and drive up. Part of the round started at the bottom in those big houses in the Croxley Woods, so I would probably get down as far as that, and then do the rest of the round with him. And often he had his – I think his nephew or it even may have been his son, I can’t remember – on the cart as well, and so we would rush up and down the paths with the milk, but we had the fun of being driven around behind the horse, which was lovely. Very exciting.

Int: How long was the horse and cart deliveries in Croxley? When did that stop?

JM: I don’t know. I presume some time in the l950s, late 50s, 60s. I’m trying to think – because I went to university in 1956 so I mean I had rather outgrown going round with the milk cart by then! So I’m talking probably when I was about ten. You know this was a really exciting thing and of course my mother had no – there was so much less worry about being allowed to do things like that. I mean she didn’t know the milkman personally. I mean she’d obviously seen him, paying him and so on, and I suppose she just felt it was safe, because it was in the daytime and I mean as far as I know it didn’t occur to anybody. I mean we were allowed – again when I was much younger than that – to go out into the fields. You’d go – probably about two or three of us – and nearly always all girls, because Watford Grammar was girls, and so two or three of us would go out and walk down to the Chess River and so on, and I mean we were probably seven or eight, and again it just wasn’t a worry.

Int: What do you think your Mum would think of Croxley today?

JM: I think she’d be astonished, probably, because it’s so much more cosmopolitan now than it was then. I mean in those days it was entirely, I would say, white. Two of my friends from school lived in Dickinson Avenue and one – the wife was German, and that was probably the only foreign person in the village. To our knowledge. And you never saw anybody noticeably of another race at all. Either in Rickmansworth and I don’t think in Watford.

Int: What was it like socially for your Mum as a widowed woman?

JM: Very, very, very not social, because I think she was – I know that when we had an electrician come to do the lights, I think she was extremely worried that as a woman on her own with a young child, to get any kind of reputation, so she didn’t go out, as far as I know, she wasn’t a member of the church or any kind of social thing. I can’t remember ever having people here apart from my grandmother and aunt, her sister, who lived in Dickinson Avenue, and that’s about all I can ever remember coming to the house or going to see.

Int: Was it just ‘not done’ for the single woman to (JM: Absolutely not done) go to the pubs on the Green, or …?

JM: Oh no way! My goodness! No, that would definitely not – you couldn’t possibly! I mean that went on well into the 70s. I mean you just – absolutely you couldn’t possibly.

Int: So you feel it went on that long, that being a single woman was difficult, to be on your own.

JM: Yes. My mother was born in 1904, and although she was very forward-looking in many ways, that was the sort of generational thing, you just didn’t do it. And there was a long time when I wouldn’t have, either.

Int: And the Dickinson Institute – you didn’t …?

JM: No. I mean if there was a flower show or something we went to that, but I can’t remember – there were dances and things, I believe, but we certainly never went to it. And I think, you know, again she wasn’t interested. So we would go to London.

Int: Yes.

JM: We went to the cinema a bit, but not a lot.

Int: What’s kept you living in Croxley?

JM: My house! Because I love my house, I love having a garden. A lot of people – because my entire working life was in London – a lot of people asked me why didn’t I sell and go to London, but I mean what I could have sold this house for I couldn’t have possibly have had anything like it in London. So I preferred to be here. I mean the travelling was a bit of a nuisance, but it didn’t matter, one was just used to it, and there were plenty of trains before I could drive, so it was no problem.

Int: After university what did you go into first as a job?

JM: I left university and then I did what a lot of women did in those days, because we’re talking about 1959, I did a secretarial course, a six months graduates’ secretarial course, and then I did six weeks in the Town Hall in Watford as my very, very first job, and I then went into the BBC, where I spent my entire working life. And worked my way up from secretary to being a producer in the end.

Int: Did you find as time went by there were more opportunities for women (JM: oh yes) in a company like the BBC?

JM: Yes, definitely. But again I never came up particularly against any kind of discrimination against women, because right from the very early days there had been quite powerful women in the BBC. On the whole women went in on a lower rank but you weren’t stopped from then on working your way up if you wanted to and if you could. And I started in Overseas Talks so this was in the Overseas Service based in Bush House, and that was much less formal and much more, obviously, multi-cultural. You always started, if you were a secretary, you started in radio, and then you learned how the BBC did things, and you probably stayed there two or three years, and then if you wanted to you would move to television, which was always considered a step up and was better paid. But Broadcasting House was always much more formal than Bush House was, and so it was quite an easy atmosphere and quite easy to make progress if you wanted to. But, equally of course it meant with my working hours and the fact that when I was in television sometimes you were quite late or you were away filming, I did not really have a life in Croxley although I lived here, my life wasn’t, my friends were in London through the BBC, and I didn’t do much locally, which is why there is a long gap without noticing much what happened in Croxley.

Int: A decade.

JM: Yes, which went on round me without me taking much part in it, I’m afraid!

Int: Which decade did you think of as seeing the most change in Croxley, though, because you must have observed so many changes?

JM: Gosh, well I don’t – I mean this is the awful thing, I think it just all happened so slowly, you know, you’re not aware of it. Well I think shops closing probably are things that you’re aware of because when I was working going shopping on Saturday started off just going to Rickmansworth because of buying groceries and things, everything you bought was in Rickmansworth, and then with the big shops in Watford, you would shop in Watford if you wanted to get clothes or anything like that, on the whole, because once you’d finished work you absolutely didn’t really want to go back into London to start shopping, so life then would be round here more. But not to do anything associated with Croxley.

Int: And if you just wanted some milk or some extra bread, where did you used to shop? Was there the Co-op?

JM: 1942. But I mean he was gone – because I was born January 1938 and he went into training as soon as the war started, because – because of his age he knew he would be called up, so you know it looked better, shall we say, if he volunteered. So he did and so he went away very soon after the outbreak of the war because of the training before you actually went into the Forces. So I never saw him.

Int: And your mum found herself as a single mother.

JM: Oh absolutely, yes.

Int: Very early on in her life, really, and at a very difficult time (JM: Yes). Did she work?

JM: Well, she was a trained infants teacher, so what she did was set up a small nursery school – because I think you could only have – I can’t remember how many pupils – in the house, but because this house wasn’t arranged as a nursery school, even though things weren’t as strict then as they would be now, with what facilities you had, the fact that this was just an ordinary house … so she managed that. She got a war widow’s pension, which I think – I mean I don’t know when these sort of things started or quite – I mean I think my father must have sent something – whatever his army pay was must have come to her. But I mean she did work as a teacher in London before I was born. Then there was that period when I was too young for her to go out to work, but as soon as I was at school she went back to teaching, because as a teacher her hours were more or less the same as mine.

Int: So did your mum run the nursery school from here in the house?

JM: Yes. So if it was raining it was in this room, actually, and she would have little tables and chairs and things, and if it was fine we were in the garden. Because this was literally, you know a nursery school, so these were pre-school children.

Int: Including you.

JM: Including me, absolutely, yes!

Int: And when you were a little bit older, then, how did you entertain yourself? What did you do when you weren’t at school?

JM: Well, I had school friends and we would play in the road, which, you know, is inconceivable now, and we would have skipping and things like that. And then listening to the wireless and reading and my mother read to me before I was doing much reading for myself, so books were always part of my life.

Int: Do you remember your favourite books when you were growing up, as a little girl?

JM: Gosh. I think Dr Dolittle, things like that. I mean she was very concerned we got all the sort of classic children’s books, Mary Poppins and Mary Plain – I don’t know if you remember those, about the bear in the bear pits of Berne.

Int: No I don’t remember those.

JM: So there was those and Millions of Cats, which I absolutely loved, because I’ve always liked cats, and that started when I was very young. I think that’s about it, really, that I can think of particularly. Arthur Ransome of course. All the expected ones for children in the 1940s, so the things that were popular in the 1930s or written in the 1930s.

Int: So, going back to shopping, you said you used to trail round with the ration book and everything when you were – well, becoming a teenager then – can you remember at the end of the 1940s early 1950s where most of the shops were around here that you used to go to?

JM: Well, by then we were probably be going to Rickmansworth. At the top of Scots Hill there was a very good grocer’s, there was the greengrocer there as well, and then there was Luxton’s the newsagent. There was Window’s the haberdashery, the little haberdashery shop, which was lovely, and there was bicycle shop I can vaguely remember there. And then in New Road there were the butchers, there were – I think there were two grocers, another greengrocer. There were butchers in Watford Road and various other shops there, but somehow or other I never associate going much to the Watford Road shops, it was always New Road or Scots Hill, and then to Rickmansworth, because the library was in Rickmansworth, and I can remember going to the children’s library there, which was sort of near where Watersmeet is now, and I can remember – it was a wooden building and I can absolutely remember the smell of it, but it was such a good library, really excellent. Also the fishmonger was in Rickmansworth, there was no fishmonger in Croxley, so you would have to go there. And there were two cinemas in Rickmansworth then, so occasionally we would go to the cinema. Sometimes we would walk but more often get the bus, because there were so many more buses – I mean you’d just walk round to the bus stop and get the bus down to Ricky.

Int: Where did the buses stop in New Road?

JM: Well, yes but we would go to the bus stop where – I mean the bus stops haven’t changed, so from this house one would go to the bus stop near the church, it’s nearer.

Int: So you’re becoming a teenager and – what, in ‘51? And obviously throughout the fifties, what are your memories of that sort of time. Did Croxley change very much in those postwar years?

JM: I don’t know, really. I suppose not. There again, because I went to school in Watford, this is my problem when people ask me about Croxley. I was in school in Watford, I went to university in London, and I worked in London, so I don’t actually have a whole lot of connections with Croxley, really. When I was in university, I lived in London, so I didn’t come home much then. So after my childhood, really, I don’t have much memory of Croxley as such, or being terribly aware of things changing or what was going on.

Int: Of course the station was there, so it was very convenient.

JM: Oh yes, absolutely, and we used to go to London a lot, because my mother liked London and had lived in London before she was married and during her early married life, and she was very keen on the theatre, so we would go to the theatre a lot. And even during the war we went to matinees, various foreign companies for some reason came – I can’t remember whether it was literally during wartime but I think it was. So we would go to a matinee which was safe or as safe as anything, and then we would go to the theatre a lot.

Int: On the Met Line.

JM: On the Met Line. The nice old brown trains. And I mean sometimes there were things like workmen’s trains – you could get cheap fares – I think maybe before 8 o’clock or even earlier than that – and we would do that and it was a way of saving money and it meant you had a jolly long day in London.

Int: Can you remember how much it cost to go to London?

JM: No, because I didn’t pay! But I mean it wasn’t very much. Now with Oyster cards you aren’t aware of how much it costs and that’s the terrible thing.

Int: Did you have any jobs growing, maybe in Croxley?

JM: I used to do a paper round, from school, that was ten shillings a week, I remember. That was from Luxton’s, and I did Watford Road and Bateman Road mostly. But I shared the round with a school friend who lived down in Watford Road. We would do one week on and one week off and when it was my week off if someone had let him down he would telephone and say could I come in, and so I would have to go in and do a spare round.

Int: And that was delivering the newspaper before you went to school?

JM: Oh yes, absolutely, because people had to have their newspapers early so you know – because I would need to get a bus from here to go to school probably soonish after 8, so you’d go, you know, half past six to do the paper round.

Int: Did you go on a bicycle (JM: Yes) or walking?

JM: No, I’d bicycle, and with an extraordinarily heavy bag of newspapers when I started and he did have some bikes with the basket in front, but I never had one of those, I always used to use my own bike. But it was quite heavy going. And I also – just more for fun really, because milk was delivered in a horse and cart in the early days and I was crazy about horses, very little girl and ponies kind of thing, so at the weekend, this was not a thing I could do during the week, definitely, I used to walk down through the woods to meet him, because the Poulter’s Dairy stables were in Ricky, and he would load up his cart and drive up. Part of the round started at the bottom in those big houses in the Croxley Woods, so I would probably get down as far as that, and then do the rest of the round with him. And often he had his – I think his nephew or it even may have been his son, I can’t remember – on the cart as well, and so we would rush up and down the paths with the milk, but we had the fun of being driven around behind the horse, which was lovely. Very exciting.

Int: How long was the horse and cart deliveries in Croxley? When did that stop?

JM: I don’t know. I presume some time in the l950s, late 50s, 60s. I’m trying to think – because I went to university in 1956 so I mean I had rather outgrown going round with the milk cart by then! So I’m talking probably when I was about ten. You know this was a really exciting thing and of course my mother had no – there was so much less worry about being allowed to do things like that. I mean she didn’t know the milkman personally. I mean she’d obviously seen him, paying him and so on, and I suppose she just felt it was safe, because it was in the daytime and I mean as far as I know it didn’t occur to anybody. I mean we were allowed – again when I was much younger than that – to go out into the fields. You’d go – probably about two or three of us – and nearly always all girls, because Watford Grammar was girls, and so two or three of us would go out and walk down to the Chess River and so on, and I mean we were probably seven or eight, and again it just wasn’t a worry.

Int: What do you think your Mum would think of Croxley today?

JM: I think she’d be astonished, probably, because it’s so much more cosmopolitan now than it was then. I mean in those days it was entirely, I would say, white. Two of my friends from school lived in Dickinson Avenue and one – the wife was German, and that was probably the only foreign person in the village. To our knowledge. And you never saw anybody noticeably of another race at all. Either in Rickmansworth and I don’t think in Watford.

Int: What was it like socially for your Mum as a widowed woman?

JM: Very, very, very not social, because I think she was – I know that when we had an electrician come to do the lights, I think she was extremely worried that as a woman on her own with a young child, to get any kind of reputation, so she didn’t go out, as far as I know, she wasn’t a member of the church or any kind of social thing. I can’t remember ever having people here apart from my grandmother and aunt, her sister, who lived in Dickinson Avenue, and that’s about all I can ever remember coming to the house or going to see.

Int: Was it just ‘not done’ for the single woman to (JM: Absolutely not done) go to the pubs on the Green, or …?

JM: Oh no way! My goodness! No, that would definitely not – you couldn’t possibly! I mean that went on well into the 70s. I mean you just – absolutely you couldn’t possibly.

Int: So you feel it went on that long, that being a single woman was difficult, to be on your own.

JM: Yes. My mother was born in 1904, and although she was very forward-looking in many ways, that was the sort of generational thing, you just didn’t do it. And there was a long time when I wouldn’t have, either.

Int: And the Dickinson Institute – you didn’t …?

JM: No. I mean if there was a flower show or something we went to that, but I can’t remember – there were dances and things, I believe, but we certainly never went to it. And I think, you know, again she wasn’t interested. So we would go to London.

Int: Yes.

JM: We went to the cinema a bit, but not a lot.

Int: What’s kept you living in Croxley?

JM: My house! Because I love my house, I love having a garden. A lot of people – because my entire working life was in London – a lot of people asked me why didn’t I sell and go to London, but I mean what I could have sold this house for I couldn’t have possibly have had anything like it in London. So I preferred to be here. I mean the travelling was a bit of a nuisance, but it didn’t matter, one was just used to it, and there were plenty of trains before I could drive, so it was no problem.

Int: After university what did you go into first as a job?

JM: I left university and then I did what a lot of women did in those days, because we’re talking about 1959, I did a secretarial course, a six months graduates’ secretarial course, and then I did six weeks in the Town Hall in Watford as my very, very first job, and I then went into the BBC, where I spent my entire working life. And worked my way up from secretary to being a producer in the end.

Int: Did you find as time went by there were more opportunities for women (JM: oh yes) in a company like the BBC?

JM: Yes, definitely. But again I never came up particularly against any kind of discrimination against women, because right from the very early days there had been quite powerful women in the BBC. On the whole women went in on a lower rank but you weren’t stopped from then on working your way up if you wanted to and if you could. And I started in Overseas Talks so this was in the Overseas Service based in Bush House, and that was much less formal and much more, obviously, multi-cultural. You always started, if you were a secretary, you started in radio, and then you learned how the BBC did things, and you probably stayed there two or three years, and then if you wanted to you would move to television, which was always considered a step up and was better paid. But Broadcasting House was always much more formal than Bush House was, and so it was quite an easy atmosphere and quite easy to make progress if you wanted to. But, equally of course it meant with my working hours and the fact that when I was in television sometimes you were quite late or you were away filming, I did not really have a life in Croxley although I lived here, my life wasn’t, my friends were in London through the BBC, and I didn’t do much locally, which is why there is a long gap without noticing much what happened in Croxley.

Int: A decade.

JM: Yes, which went on round me without me taking much part in it, I’m afraid!

Int: Which decade did you think of as seeing the most change in Croxley, though, because you must have observed so many changes?

JM: Gosh, well I don’t – I mean this is the awful thing, I think it just all happened so slowly, you know, you’re not aware of it. Well I think shops closing probably are things that you’re aware of because when I was working going shopping on Saturday started off just going to Rickmansworth because of buying groceries and things, everything you bought was in Rickmansworth, and then with the big shops in Watford, you would shop in Watford if you wanted to get clothes or anything like that, on the whole, because once you’d finished work you absolutely didn’t really want to go back into London to start shopping, so life then would be round here more. But not to do anything associated with Croxley.

Int: And if you just wanted some milk or some extra bread, where did you used to shop? Was there the Co-op?

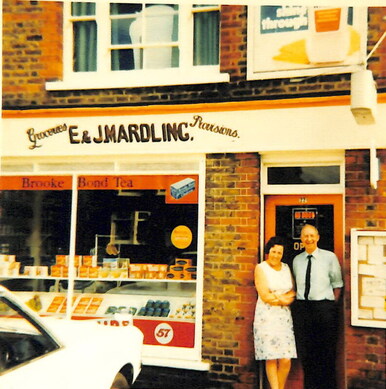

Mr & Mrs Mardling's shop on the corner New Road and Yorke Road

Mr & Mrs Mardling's shop on the corner New Road and Yorke Road

JM: I had milk delivered. There was a little shop at the top of Yorke Road, run by some people called Mardling, a little grocer’s shop, so that was a very good sort of emergency thing.

Int: At the top of Yorke Road where it intersects with New Road?

JM: Yes, on the corner. I didn’t shop at the Co-op, I didn’t like it very much. I would have bought everything in Rickmansworth. And there were shops near the BBC so you could, if you really wanted to, you could buy stuff there as well. But definitely the weekly shop was Rickmansworth.

Int: As a little girl, if you were going to get some sweets or something, was there anything like a sweet shop or ice cream shop in Croxley?

JM: Luxton’s was the newsagent cum sweet shop. So we would go there for sweets. There was Grillo’s ice cream which had a little ice cream van which would be parked near the station, so you would get something there sometimes. And, you know, as I said the lovely thing like buying cherries on the Green, which was gorgeous, lovely whiteheart cherries, unforgettable. It was really sad when that stopped.

Int: The cherry picking, yes, the picnics on the Green.

JM: Yes. And in the cherry season they just hired a big table and you just went and bought pounds of cherries, regularly, while the cherry season was on. It was lovely.

Int: Yes, an event specific to Croxley. Are there any other events that stand out?

JM: Well, the Revels of course, which was great fun. That was later, when it sort of got going after the War again. That was great fun.

Int: And there was the fire, of course, the Guildhouse burning down in the Sixties.

JM: I don’t remember that at all. I wasn’t aware of that. One heard about it more than actually seeing it.

Int: It was only the hall, anyway, wasn’t it? I think.

JM: Yes. I mean that was sad, when that was pulled down and the flats were built. That was something that at one point was at the absolute heart of Croxley. I’ve been reading a lot of the Parish Magazines and what a central place it was for Croxley! Which again I don’t know how much of that went on even into the 30s. Presumably as people got more mobile there were other things that they did with the coming of cars and so on. I mean because there were always wealthy bits of Croxley as well as the perfectly ordinary working class parts of Croxley, and I think therefore because of the good railway line which came quite early, an awful lot of the men went off in the mornings to work in London, and then in those days a lot more women stayed at home and it wasn’t – not ‘not done’, it just didn’t happen.

Int: No. Even in the 60s and 70s they would have been mainly at home, I suppose.

JM: Yes. I think – well, certainly I think up into, you know, within the 50s definitely. I mean by the time I had started work, which was 1960, we were all commuting and that was a lot of women as well. Because when I started at the BBC I would commute by train.

Int: Did your mum ever drive?

JM: No. No – I mean, she couldn’t have afforded a car, I think, at all, even if she’d wanted to.

Int: So that is a big change in Croxley that there’s so many cars.

JM: Yes, I mean the loss of front gardens in New Road is really sad.

Int: So it would have looked so different.

JM: Yes, it did, and you know everybody had little gardens in front.

Int: Yes that’s what I meant by the green spaces.

JM: Oh I see, gardens.

Int: Now there’s so much concrete, isn’t there?

JM: Well, yes, quite. I mean one is very lucky if you have enough space to have a garage and still have a garden in front. And of course with New Road, really there’s no alternative – you’ve got to destroy your garden because the road is just – trying to park in it would be awful, I think. And now more and more people have not only one car per household but more than one.

Int: When did you start driving?

JM: I think about 1963, because when my mother died the house became mine and I managed for a couple of years by myself but then I couldn’t afford to run a house this size and travel, so I ended up with two other women, secretaries from the BBC, in the end, renting. And then one of us could drive so once she came it was a case of ‘why not get a car?’ And my uncle helped me to buy one, a small car, and then I had driving lessons, and from then on we started commuting to work, because we were all in the BBC, we could commute by car.

Int: Going into London?

JM: Oh yes. Well, it wasn’t a pain as it is now. And it was possible to park. And as I got further up the hierarchy I got parking space in the BBC’s own car park.

Int: So in those early days you were able to keep this house by renting out some of the rooms to friends?

JM: Yes, absolutely, yes. I’m still friends with both of the people who were here then. One left to get married and she has her own family and doesn’t live near here, and the other one – she has her own home as well but still comes up here, still keeps a room in my house, actually, and we do a lot of things together in London and she would drive up and stay a couple of nights or three days or whatever while we cram in things to do and then we’re both very happy having our own spaces and our own time but it's nice to have the contact.

Int: And your mum started off renting this house? How was she able to buy it?

JM: Well, she rented it because – it’s semi-detached and the landlady lived in the other half, and she was elderly then and she got more and more elderly and her potential heirs realised that it would make sense to offer it to my mother although the landlady was still alive at the time, and then she was offered it for £850, would you believe! But that - £850 then was, you know, like £800,000 almost, and I mean she was just about for some reason able to get a mortgage. I know there was an awful amount of fuss because there again, being a widow – I mean she had a perfectly responsible job and safe job, but again it was unusual to give a mortgage to a woman without a man to back her up. But she got the mortgage somehow and that was how she managed to buy it.

Int: What year was that that she managed to buy the house?

JM: I think about 1946, 45, 46 – I think it was just post-war. And then – do you know the Old Boys’ School, which was in Watford Road? That had land at the back of my house and there was a pub, the Duke of York, which was the most downmarket pub in Croxley at the time, and – not horrible, but it was definitely the roughest of the pubs – and there was a lot of land which had been owned by the headmaster of the Old Boys School, Neggy Wilson. I believe he got it with the idea of making it a playing field for the boys’ school, but nothing ever happened, and then he died and that land came up as well, and my mother heard that the pub were going to buy it as a beer garden and she managed to leap in and with the help of our neighbours, Mr. Sharp, I think they lent her some money and she managed to buy that land, more because she was worried about the idea of the beer garden surrounding us than for any possible reason of cultivating it. We left it – it was left wild for absolutely ages, until finally I managed to get a gardener and we managed to get it back into control.

Int: Very enterprising! So the original garden was much smaller than it is now (JM: Yes) because your mum was able to buy that land.

JM: Absolutely. But also these houses were built in 1869 and at that stage Yorke Road had virtually no other houses in it, apart from a couple right up at the top, and then in the 1920s when Dickinson Avenue was projected, they wanted to get more houses between Dickinson Avenue and these houses, and in order to squash in I think there’s four or six houses, they took some of the land at the side of this house to make the space for those houses and they made this house have an L-shaped garden so that it had the same amount of land as the other half of the semi-detached, but round at the back of it. And then my mother got this land at the bottom. So it’s now – it’s much bigger than anybody realises from the road.

Int: The original house must have had quite a big piece of land at the side of it.

JM: Well, it didn’t really. I mean it had probably to the side about twice as much as it has now, just that side. But it didn’t extend all that way back. I mean it was a fairly sizeable. But then all the houses those days had gardens, nearly all at the back, because people grew things.

Int: And does your house have quite a lot of original features?

JM: Yes. Well, it’s been modernised, but keeping the same style, I think you could say. It’s a weird house actually, because it’s very badly designed. We think it was probably just put together by a local carpenter or a local builder who just put up two houses. And in the roof – I mean there was no division between the two sides, which we had to have put in because you couldn’t sell it that way. And the roof timbers are really – I mean I don’t know how the thing’s standing, really. It looks a really botched job.

Int: Well it has stood the test of time!

JM: It has stood the test of time. And the fact, you know, that the door is right opposite the fireplace, which is most unusual, and of course makes a terrible draught. I mean it doesn’t so much now because I’ve got double glazing and everything but in those days when we first came, there was no heating of course bar the open fires, and I have two beautiful open fires in the bedrooms as well. And the bathroom must have been put in some time in the thirties, I think. It took part of the huge front bedroom to make a bathroom and lavatory and that had been done. But I mean things like the doors are actually the original doors, and the layout of the house hasn’t changed. We used to have a well, which is still there but covered up now in the garden. I doubt very much it was ever used for drinking – well, it might have been used for drinking water for all I know – but I don’t think so. It might have been for washing more than anything else. I think it was more of a cistern than a well, but it was quite deep and quite big and it had a trapdoor on top – between the two houses then.

Thanks from Ints. and regrets for not remembering more about changes from JM.

JM: Of course there’s houses built across the road now – that was all a big orchard of the house before all those flats were built.

Int: Who did the orchard belong to?

JM: I don’t know - whoever owned the house – I can’t remember the name of them now – Outspan I think was the house. The house was bought later by Dr. Russell. He was there in the late 50s. Because there were always quite a few doctors in the – in Croxley. And one dentist on the Green.

Int: Did your mum take you to a local doctor?

JM: Oh yes. But we went actually to the doctor in Rickmansworth, because I mean my mother didn’t like the doctor, the main doctor here, who was Dr Miller, who lived in Lindiswara, a house called Lindiswara, where Lindiswara Court is now. She didn’t get on with him, so we went to a doctor in Rickmansworth, Dr. Salmon. And strong memories of having measles actually – I’d forgotten about that. The doctor would come for that, and being in the bedroom in the front which wasn’t my bedroom – in the dark, because people were worried in those days about measles, it could affect your eyes, and having M & B tablets crushed to take – and that was about the only thing that you could have. Because I mean measles then – this was early 1950s or late 1940s and I was still pretty young. So it was still a pretty serious illness then. And I mean of course the National Health Service had started just about then, so it wasn’t, you know, too frightening to have to call the doctor out.

Int: Well, thank goodness to have come through all that.

JM: Well, one did in those days! Because Watford Grammar when I first went was fee-paying because the 1944 Education Act was only just coming in when I started there, so I think for a term or so it was fee-paying and we were the last intake of 7 year olds so we went up, just about twenty of us went through the whole school until the 11-plus which we had to sit along with everybody else – funnily enough we all passed!

Int. So you were the last intake before it just became a high school?

JM: Yes. Well, it was a grammar school. I mean it always was – I mean it’s still called Watford Grammar School, of course.

Int: But it was at the site it is now?

JM: Yes. Yes, I mean it’s hugely extended now. And our little bit – the younger children were in Lady’s Close, which still belongs to the school and they do still have classes in it. I went a couple of years ago - they had a lovely open day - and the headmistress actually lived in a flat above the classrooms in Lady’s Close. She was a frightening woman, very, very academic. I mean it was a very academic school in those days. But my mother was determined that I should try to go – because it had entrance exams and she very much wanted me to try for everything and was very pleased when I got in. I mean she believed a great deal in education, being a teacher herself, so I was very lucky having a home backup throughout my career really, throughout my time.

Int: You had your own personal tutor.

JM: Yes!

More thanks and excuses.

Int: At the top of Yorke Road where it intersects with New Road?

JM: Yes, on the corner. I didn’t shop at the Co-op, I didn’t like it very much. I would have bought everything in Rickmansworth. And there were shops near the BBC so you could, if you really wanted to, you could buy stuff there as well. But definitely the weekly shop was Rickmansworth.

Int: As a little girl, if you were going to get some sweets or something, was there anything like a sweet shop or ice cream shop in Croxley?

JM: Luxton’s was the newsagent cum sweet shop. So we would go there for sweets. There was Grillo’s ice cream which had a little ice cream van which would be parked near the station, so you would get something there sometimes. And, you know, as I said the lovely thing like buying cherries on the Green, which was gorgeous, lovely whiteheart cherries, unforgettable. It was really sad when that stopped.

Int: The cherry picking, yes, the picnics on the Green.

JM: Yes. And in the cherry season they just hired a big table and you just went and bought pounds of cherries, regularly, while the cherry season was on. It was lovely.

Int: Yes, an event specific to Croxley. Are there any other events that stand out?

JM: Well, the Revels of course, which was great fun. That was later, when it sort of got going after the War again. That was great fun.

Int: And there was the fire, of course, the Guildhouse burning down in the Sixties.

JM: I don’t remember that at all. I wasn’t aware of that. One heard about it more than actually seeing it.

Int: It was only the hall, anyway, wasn’t it? I think.

JM: Yes. I mean that was sad, when that was pulled down and the flats were built. That was something that at one point was at the absolute heart of Croxley. I’ve been reading a lot of the Parish Magazines and what a central place it was for Croxley! Which again I don’t know how much of that went on even into the 30s. Presumably as people got more mobile there were other things that they did with the coming of cars and so on. I mean because there were always wealthy bits of Croxley as well as the perfectly ordinary working class parts of Croxley, and I think therefore because of the good railway line which came quite early, an awful lot of the men went off in the mornings to work in London, and then in those days a lot more women stayed at home and it wasn’t – not ‘not done’, it just didn’t happen.

Int: No. Even in the 60s and 70s they would have been mainly at home, I suppose.

JM: Yes. I think – well, certainly I think up into, you know, within the 50s definitely. I mean by the time I had started work, which was 1960, we were all commuting and that was a lot of women as well. Because when I started at the BBC I would commute by train.

Int: Did your mum ever drive?

JM: No. No – I mean, she couldn’t have afforded a car, I think, at all, even if she’d wanted to.

Int: So that is a big change in Croxley that there’s so many cars.

JM: Yes, I mean the loss of front gardens in New Road is really sad.

Int: So it would have looked so different.

JM: Yes, it did, and you know everybody had little gardens in front.

Int: Yes that’s what I meant by the green spaces.

JM: Oh I see, gardens.

Int: Now there’s so much concrete, isn’t there?

JM: Well, yes, quite. I mean one is very lucky if you have enough space to have a garage and still have a garden in front. And of course with New Road, really there’s no alternative – you’ve got to destroy your garden because the road is just – trying to park in it would be awful, I think. And now more and more people have not only one car per household but more than one.

Int: When did you start driving?

JM: I think about 1963, because when my mother died the house became mine and I managed for a couple of years by myself but then I couldn’t afford to run a house this size and travel, so I ended up with two other women, secretaries from the BBC, in the end, renting. And then one of us could drive so once she came it was a case of ‘why not get a car?’ And my uncle helped me to buy one, a small car, and then I had driving lessons, and from then on we started commuting to work, because we were all in the BBC, we could commute by car.

Int: Going into London?

JM: Oh yes. Well, it wasn’t a pain as it is now. And it was possible to park. And as I got further up the hierarchy I got parking space in the BBC’s own car park.

Int: So in those early days you were able to keep this house by renting out some of the rooms to friends?

JM: Yes, absolutely, yes. I’m still friends with both of the people who were here then. One left to get married and she has her own family and doesn’t live near here, and the other one – she has her own home as well but still comes up here, still keeps a room in my house, actually, and we do a lot of things together in London and she would drive up and stay a couple of nights or three days or whatever while we cram in things to do and then we’re both very happy having our own spaces and our own time but it's nice to have the contact.

Int: And your mum started off renting this house? How was she able to buy it?

JM: Well, she rented it because – it’s semi-detached and the landlady lived in the other half, and she was elderly then and she got more and more elderly and her potential heirs realised that it would make sense to offer it to my mother although the landlady was still alive at the time, and then she was offered it for £850, would you believe! But that - £850 then was, you know, like £800,000 almost, and I mean she was just about for some reason able to get a mortgage. I know there was an awful amount of fuss because there again, being a widow – I mean she had a perfectly responsible job and safe job, but again it was unusual to give a mortgage to a woman without a man to back her up. But she got the mortgage somehow and that was how she managed to buy it.

Int: What year was that that she managed to buy the house?

JM: I think about 1946, 45, 46 – I think it was just post-war. And then – do you know the Old Boys’ School, which was in Watford Road? That had land at the back of my house and there was a pub, the Duke of York, which was the most downmarket pub in Croxley at the time, and – not horrible, but it was definitely the roughest of the pubs – and there was a lot of land which had been owned by the headmaster of the Old Boys School, Neggy Wilson. I believe he got it with the idea of making it a playing field for the boys’ school, but nothing ever happened, and then he died and that land came up as well, and my mother heard that the pub were going to buy it as a beer garden and she managed to leap in and with the help of our neighbours, Mr. Sharp, I think they lent her some money and she managed to buy that land, more because she was worried about the idea of the beer garden surrounding us than for any possible reason of cultivating it. We left it – it was left wild for absolutely ages, until finally I managed to get a gardener and we managed to get it back into control.

Int: Very enterprising! So the original garden was much smaller than it is now (JM: Yes) because your mum was able to buy that land.

JM: Absolutely. But also these houses were built in 1869 and at that stage Yorke Road had virtually no other houses in it, apart from a couple right up at the top, and then in the 1920s when Dickinson Avenue was projected, they wanted to get more houses between Dickinson Avenue and these houses, and in order to squash in I think there’s four or six houses, they took some of the land at the side of this house to make the space for those houses and they made this house have an L-shaped garden so that it had the same amount of land as the other half of the semi-detached, but round at the back of it. And then my mother got this land at the bottom. So it’s now – it’s much bigger than anybody realises from the road.

Int: The original house must have had quite a big piece of land at the side of it.

JM: Well, it didn’t really. I mean it had probably to the side about twice as much as it has now, just that side. But it didn’t extend all that way back. I mean it was a fairly sizeable. But then all the houses those days had gardens, nearly all at the back, because people grew things.

Int: And does your house have quite a lot of original features?

JM: Yes. Well, it’s been modernised, but keeping the same style, I think you could say. It’s a weird house actually, because it’s very badly designed. We think it was probably just put together by a local carpenter or a local builder who just put up two houses. And in the roof – I mean there was no division between the two sides, which we had to have put in because you couldn’t sell it that way. And the roof timbers are really – I mean I don’t know how the thing’s standing, really. It looks a really botched job.

Int: Well it has stood the test of time!

JM: It has stood the test of time. And the fact, you know, that the door is right opposite the fireplace, which is most unusual, and of course makes a terrible draught. I mean it doesn’t so much now because I’ve got double glazing and everything but in those days when we first came, there was no heating of course bar the open fires, and I have two beautiful open fires in the bedrooms as well. And the bathroom must have been put in some time in the thirties, I think. It took part of the huge front bedroom to make a bathroom and lavatory and that had been done. But I mean things like the doors are actually the original doors, and the layout of the house hasn’t changed. We used to have a well, which is still there but covered up now in the garden. I doubt very much it was ever used for drinking – well, it might have been used for drinking water for all I know – but I don’t think so. It might have been for washing more than anything else. I think it was more of a cistern than a well, but it was quite deep and quite big and it had a trapdoor on top – between the two houses then.

Thanks from Ints. and regrets for not remembering more about changes from JM.

JM: Of course there’s houses built across the road now – that was all a big orchard of the house before all those flats were built.

Int: Who did the orchard belong to?

JM: I don’t know - whoever owned the house – I can’t remember the name of them now – Outspan I think was the house. The house was bought later by Dr. Russell. He was there in the late 50s. Because there were always quite a few doctors in the – in Croxley. And one dentist on the Green.

Int: Did your mum take you to a local doctor?

JM: Oh yes. But we went actually to the doctor in Rickmansworth, because I mean my mother didn’t like the doctor, the main doctor here, who was Dr Miller, who lived in Lindiswara, a house called Lindiswara, where Lindiswara Court is now. She didn’t get on with him, so we went to a doctor in Rickmansworth, Dr. Salmon. And strong memories of having measles actually – I’d forgotten about that. The doctor would come for that, and being in the bedroom in the front which wasn’t my bedroom – in the dark, because people were worried in those days about measles, it could affect your eyes, and having M & B tablets crushed to take – and that was about the only thing that you could have. Because I mean measles then – this was early 1950s or late 1940s and I was still pretty young. So it was still a pretty serious illness then. And I mean of course the National Health Service had started just about then, so it wasn’t, you know, too frightening to have to call the doctor out.

Int: Well, thank goodness to have come through all that.

JM: Well, one did in those days! Because Watford Grammar when I first went was fee-paying because the 1944 Education Act was only just coming in when I started there, so I think for a term or so it was fee-paying and we were the last intake of 7 year olds so we went up, just about twenty of us went through the whole school until the 11-plus which we had to sit along with everybody else – funnily enough we all passed!

Int. So you were the last intake before it just became a high school?

JM: Yes. Well, it was a grammar school. I mean it always was – I mean it’s still called Watford Grammar School, of course.

Int: But it was at the site it is now?

JM: Yes. Yes, I mean it’s hugely extended now. And our little bit – the younger children were in Lady’s Close, which still belongs to the school and they do still have classes in it. I went a couple of years ago - they had a lovely open day - and the headmistress actually lived in a flat above the classrooms in Lady’s Close. She was a frightening woman, very, very academic. I mean it was a very academic school in those days. But my mother was determined that I should try to go – because it had entrance exams and she very much wanted me to try for everything and was very pleased when I got in. I mean she believed a great deal in education, being a teacher herself, so I was very lucky having a home backup throughout my career really, throughout my time.

Int: You had your own personal tutor.

JM: Yes!

More thanks and excuses.