Brian & Sheila Chandler - Memories of Croxley Green

Recorded 11th May 2022

Recorded 11th May 2022

Int: Could you just confirm your name and the year you were born, Sheila.

SC: I’m Sheila and I was born 1947.

Int: And you?

BC: I’m Brian, and I was born in 1948.

Int: And you were both born in Croxley?

S: Yes.

Int: Where were you born, Brian?

B: I was born in the prefabs, up at the top, I think it was Primrose Lane. I’m not sure.

SC: I’m Sheila and I was born 1947.

Int: And you?

BC: I’m Brian, and I was born in 1948.

Int: And you were both born in Croxley?

S: Yes.

Int: Where were you born, Brian?

B: I was born in the prefabs, up at the top, I think it was Primrose Lane. I’m not sure.

Int: And you, Sheila?

S: I was born in Malvern Way.

Int: And can you tell us a little bit about your family – maybe where they worked.

S: Well, my dad worked at the mill.

Int: Dickinson’s.

S: In Dickinson’s. My mum, as they came from Wales, and she was a downstairs maid in one of the big houses – I can’t think what it’s called. It’s in Ricky – it’s a really big house – and that’s how she met my dad, because my dad lived – by the canal – in Gade Bank.

My mum used to come up to her auntie’s who also lived in Gade Bank and that’s how they met. My mum moved here and that was it. They didn’t go back home!

Int: And your family were connected to the mill as well?

B: Yes. My mum was born down Springfield Road. My uncle – my grandad worked down there, and his son worked down there, my father worked down there, my two brothers and me all worked down the mill. And my mum worked down there for a while, sorting. And my Auntie Dot as well.

Int: Wow – it’s quite a family concern.

B: Yes, they all worked down the mill.

Int: And do you know what your father used to do?

B: Yes. He was a number one paper maker, on the number one machine, paper maker he was.

Int: What does that mean, the number one machine?

B: Well, down the mill there was six paper making machines, and he was on number one, he was in charge of number one. They would make Queen’s Velvet, Basildon Bond, that sort of stuff. So he would be in charge, and then it would come through. […]the paper making machines they would come through on the wet end, the pulp would be pumped onto the – would shake all the water out of it, dry it out, and then push it – it was called the wet end, so it would come in as liquid there, and they would be lifted up on the [dandy roll?] which would put the name into it, and then from then it would be lifted up onto these big driers that went on and on, all the way through there, yes, and they would make the paper there.

Int: Did he enjoy his job?

B: Yes, he enjoyed it, yes. He was quite well known down there because he was quite friendly with the manager, they were like friends to begin with, you know.

Int: And that was probably during the war that you –

B: No, no. After [the war] – my dad went there. And your dad was there.

S: My dad worked there before the war, because John Dickinson’s paid my mum’s mortgage when he went away for the war, and the job was there when he came home. They looked after the families.

B: I know my grandad was there before the war. Because they went away to war and then they were welcomed back, weren’t they? And he had one of these medals, that said welcome back. Yes. Well, I gave it to Margaret.

Int: How many years did your grandad work at the mill?

B: I can’t say.

S: 52 years.

B: Oh, he worked there 52 years, yes.

Int: And do you know what your grandad did at the mill?

B: Well I know he finished up as a security officer, but I don’t know what he done before that. Bu they both of them worked on the paper making machines, you know, yes. Quite frightening when I first went down there. When I went down there, I went to the gate at Croxley there and knocked on the door, and the man said “go on, what do you want, lad?” So - fifteen and a half then I was, and I said to him “Oi, have you got any jobs, Mister?” “Hang on,” he said, and he come down, bloke came down, “sign here, you start next Monday, so be here at 9 o’clock and someone’ll show you where to go”. And then I always remember walking – the bloke picked me up and I walked through this mill and this seemed so vast, long as a street really, so vast I couldn’t believe it, as a boy, 15, how vast it was, you know. Cor blimey!

Int: And what was your first job?

B: Sample boy.

Int: And what did that involve?

B: There was like three ladies and the firm – they want a sample of the paper – and I’d go into the stores, and the stores again were so vast, you know. I had to find what paper it was, take it out and take it back to the ladies and they would roll it up in a roll and send it off. And that was my first job, yes, sample boy.

Int: Do you remember how much you got paid for that?

B: About £6 a week I think. Yes. And then from there I went to labelling up on the belt, because if you’d worked hard they’d pick you up and they’d move you on. If you was a bit of a lad and didn’t want to do nothing, they didn’t – so very quickly I was only on there for maybe a year, then I moved on to labelling up all the parcels as they come down. And there’d be two boys doing that. Some might be thrown about a little bit, but (laughter) – as lads, you know. And then from there I went into packing the boxes, and then I heard there was a job going on the guillotines, and that was about £20 a week, that was. And I was not quite 18, but I went up and knocked on Harry Taylor’s door “Come in, boy, what do you want?” I said “I’m interested in the job, you know, on the guillotines”. “You’re too young”. So I said “Oh, all right then”. I went back to work and he called me back up and he said “I’ve had a thought,” he says, “we will take you on as a guillotine operator in training, but,” he said “we couldn’t pay you the full wage”. I said “oh, I don’t mind that”. And I think I got a bit less – about £15 quid or something until I was 21, and then I got the full wage. And that was on the guillotines, and that’s where I stayed, cutting the stationery up, you know, right through as it moved. The first machine I was asked to take, it was a great big horrible machine, you had to go up steps to it, and you pulled this handle down and this knife come down and cut through the paper. I had six months training on the guillotines, cutting paper, yes.

Int: Were you still there when the mill closed?

B: Yes.

Int: 1980, so you had to move on then.

B: Yes. Well, things changed as it got more modern, the machines got better and they got faster and you know – you would get paid two and tenpence ha’penny a hundred reams – a ream of paper was ordinary size whatever you got, you know, and it would come up in big sheets, feed the big reams into the machine; at first you had to measure it, cut it by hand, you know, pull that lever down, chug, chug, chug. By the time I finished, you just pressed the button and the machine – boom, boom, boom – and that was when you turned it round and out came the paper, and you’d push it up to the women to pack in the boxes and that would be taken on the conveyor belts and things. But at first it was really slow, you know, everything was slow, really. First of all I got paid two and tenpence ha’penny a hundred – so piece work you see, so you didn’t get so much money.

S: I was born in Malvern Way.

Int: And can you tell us a little bit about your family – maybe where they worked.

S: Well, my dad worked at the mill.

Int: Dickinson’s.

S: In Dickinson’s. My mum, as they came from Wales, and she was a downstairs maid in one of the big houses – I can’t think what it’s called. It’s in Ricky – it’s a really big house – and that’s how she met my dad, because my dad lived – by the canal – in Gade Bank.

My mum used to come up to her auntie’s who also lived in Gade Bank and that’s how they met. My mum moved here and that was it. They didn’t go back home!

Int: And your family were connected to the mill as well?

B: Yes. My mum was born down Springfield Road. My uncle – my grandad worked down there, and his son worked down there, my father worked down there, my two brothers and me all worked down the mill. And my mum worked down there for a while, sorting. And my Auntie Dot as well.

Int: Wow – it’s quite a family concern.

B: Yes, they all worked down the mill.

Int: And do you know what your father used to do?

B: Yes. He was a number one paper maker, on the number one machine, paper maker he was.

Int: What does that mean, the number one machine?

B: Well, down the mill there was six paper making machines, and he was on number one, he was in charge of number one. They would make Queen’s Velvet, Basildon Bond, that sort of stuff. So he would be in charge, and then it would come through. […]the paper making machines they would come through on the wet end, the pulp would be pumped onto the – would shake all the water out of it, dry it out, and then push it – it was called the wet end, so it would come in as liquid there, and they would be lifted up on the [dandy roll?] which would put the name into it, and then from then it would be lifted up onto these big driers that went on and on, all the way through there, yes, and they would make the paper there.

Int: Did he enjoy his job?

B: Yes, he enjoyed it, yes. He was quite well known down there because he was quite friendly with the manager, they were like friends to begin with, you know.

Int: And that was probably during the war that you –

B: No, no. After [the war] – my dad went there. And your dad was there.

S: My dad worked there before the war, because John Dickinson’s paid my mum’s mortgage when he went away for the war, and the job was there when he came home. They looked after the families.

B: I know my grandad was there before the war. Because they went away to war and then they were welcomed back, weren’t they? And he had one of these medals, that said welcome back. Yes. Well, I gave it to Margaret.

Int: How many years did your grandad work at the mill?

B: I can’t say.

S: 52 years.

B: Oh, he worked there 52 years, yes.

Int: And do you know what your grandad did at the mill?

B: Well I know he finished up as a security officer, but I don’t know what he done before that. Bu they both of them worked on the paper making machines, you know, yes. Quite frightening when I first went down there. When I went down there, I went to the gate at Croxley there and knocked on the door, and the man said “go on, what do you want, lad?” So - fifteen and a half then I was, and I said to him “Oi, have you got any jobs, Mister?” “Hang on,” he said, and he come down, bloke came down, “sign here, you start next Monday, so be here at 9 o’clock and someone’ll show you where to go”. And then I always remember walking – the bloke picked me up and I walked through this mill and this seemed so vast, long as a street really, so vast I couldn’t believe it, as a boy, 15, how vast it was, you know. Cor blimey!

Int: And what was your first job?

B: Sample boy.

Int: And what did that involve?

B: There was like three ladies and the firm – they want a sample of the paper – and I’d go into the stores, and the stores again were so vast, you know. I had to find what paper it was, take it out and take it back to the ladies and they would roll it up in a roll and send it off. And that was my first job, yes, sample boy.

Int: Do you remember how much you got paid for that?

B: About £6 a week I think. Yes. And then from there I went to labelling up on the belt, because if you’d worked hard they’d pick you up and they’d move you on. If you was a bit of a lad and didn’t want to do nothing, they didn’t – so very quickly I was only on there for maybe a year, then I moved on to labelling up all the parcels as they come down. And there’d be two boys doing that. Some might be thrown about a little bit, but (laughter) – as lads, you know. And then from there I went into packing the boxes, and then I heard there was a job going on the guillotines, and that was about £20 a week, that was. And I was not quite 18, but I went up and knocked on Harry Taylor’s door “Come in, boy, what do you want?” I said “I’m interested in the job, you know, on the guillotines”. “You’re too young”. So I said “Oh, all right then”. I went back to work and he called me back up and he said “I’ve had a thought,” he says, “we will take you on as a guillotine operator in training, but,” he said “we couldn’t pay you the full wage”. I said “oh, I don’t mind that”. And I think I got a bit less – about £15 quid or something until I was 21, and then I got the full wage. And that was on the guillotines, and that’s where I stayed, cutting the stationery up, you know, right through as it moved. The first machine I was asked to take, it was a great big horrible machine, you had to go up steps to it, and you pulled this handle down and this knife come down and cut through the paper. I had six months training on the guillotines, cutting paper, yes.

Int: Were you still there when the mill closed?

B: Yes.

Int: 1980, so you had to move on then.

B: Yes. Well, things changed as it got more modern, the machines got better and they got faster and you know – you would get paid two and tenpence ha’penny a hundred reams – a ream of paper was ordinary size whatever you got, you know, and it would come up in big sheets, feed the big reams into the machine; at first you had to measure it, cut it by hand, you know, pull that lever down, chug, chug, chug. By the time I finished, you just pressed the button and the machine – boom, boom, boom – and that was when you turned it round and out came the paper, and you’d push it up to the women to pack in the boxes and that would be taken on the conveyor belts and things. But at first it was really slow, you know, everything was slow, really. First of all I got paid two and tenpence ha’penny a hundred – so piece work you see, so you didn’t get so much money.

Int: And what was your neighbourhood like in – well, you were very young in the 40s, but in the 50s – can you remember much about it?

S: Free. You could go anywhere, no worries, ride your bike down the lane. It was so simple. You didn’t have to go to Watford, because everything was here, everything you could think of. Yes, very free. Long skate down the roads because there was no cars.

B: Used to race down this road, didn’t we? Used to make box carts and race down there, as kids, yes, and roller skate down. We’d have a different craze each month. You wouldn’t see the car, you see, very rare, the odd one, but you could come down. We’d have a game of football in the street as boys. That wouldn’t worry you. Changed, hasn’t it?

Int: Which school did you go to, Sheila?

S: Malvern Way.

Int: OK, of course.

S: Green Lane, Durrants.

Int: Yes. Happy memories of school?

S: Didn’t like Malvern Way. The headmistress, Miss Hemmings, was really terrible, not being awful, but – and when later on, I think I was about twelve, we went on holiday to the Isle of Wight and we was sitting at the table and another couple with their son, and “Oh, we used to live in Croxley.” And she said “Yes, and he used to come home with his hankie soaking wet, he’d push it in his mouth because Miss Hemmings wouldn’t have any coughing or anything”. And I went “oh”.

Int: A tyrant.

S: Yes. I liked Little Green, that was lovely, and Durrants. Which is no more. That was a lovely school.

Int: You probably walked to school?

S: Oh yes. And in the winter you had to wear masks because of the smog, and if it was in the winter they let us out of school early because it was getting dark and you couldn’t see.

B: The smog, you couldn’t see across the road in the smog.

Int: I’m surprised, you know. I’ve always known about the London smogs but I didn’t realise you had smogs here as well.

B: Oh yes, yes, yes. We had them here, yes.

S: You had to listen for the traffic.

B: Yes. If you didn’t have your mask on the lady who saw you across the road would tell you off.

S: Get your mask. It’s come back to that – where’s your mask?

Int: And what kind of a mask was it?

B: Just what you’ve got now, really.

S: Yes.

Int: And where did you go to school?

B: I went to Yorke Road School, Old Boys School, Harvey Road and then to Durrants here. Yes. Miss Bridge was headmistress at Yorke Road and then was Mrs. Higby was headmistress at Old Boys School and then Harvey Road was Mr. Ford, and Durrants was Mr Jefferies, wasn’t he? Yes, I know him because he gave me a good hiding. (laughter). Give me the cane, he did, a couple of times, yes.

Int: Why did you move from Yorke Road to Old Boys to Harvey Road?

B: Well, that was the system.

Int: That was the sequence.

B: Yes. I think Harvey Road then was an early school and so you went to Yorke Road and then you moved, went to Old Boys School and then from there we went into Harvey Road, which was like chalet things there really. Mr. Ford was also my Sunday School teacher, Baptist Church. So that’s where we went. And that’s where we met, at Durrants we met.

S: He sat behind me.

Int: In which subject?

S: All.

B: All.

Int: You stayed in your form going from subject to subject. Any subjects you particularly enjoyed at Durrants, any teachers you particularly liked or disliked?

S: Mr Jefferies, he was really strict, the headmaster. If you was walking past his office and you even spoke, he’d be out there, put his mortar on ”No noise!”

B: With the mortar on the head, you knew ‘oh, going to get the cane now’.

Int: Was there a lot of corporal punishment?

B: Yes. We had one teacher, he would stand – if he was going to give the cane, he would stand on the chair and as he would jump off the chair so he would bring the stick down, and one day he stood on the chair and the stick went through the ceiling and all the class laughed so he hit all the class. They wouldn’t dare do that now, would they? No. So we all got the cane, yes. They would throw anything at you, wouldn’t they, the masters? We weren’t always innocent but, you know ...

S: The blackboard brushes.

B: A ruler, they used to hit you. Yes.

S: Didn’t do us any harm, though, did it?

B: Not really, no.

S: No.

Int: Were you keen on the sports at school?

B: That’s what I liked. I did like that, yes. I wasn’t very good at football and that sort of thing, but because I played football and I found that if you had a bad game everyone would moan at you – ‘oh go on’ – and so I thought ‘no, this ain’t for me’. Anyway I enjoyed running, I was a good runner even at school. It didn’t matter – with running it doesn’t matter if you’re first, last, it’s only yourself, isn’t it? So that’s why I run. I run at school, yes. I loved it, loved running.

Int: And you kept running?

B: Yes. Virtually I did, yes. Even when I was down at work I would come home, put my shorts on and go and run thirteen miles before I had my dinner, wouldn’t I?

Int: Where did you go?

B: Anywhere. I had friends who would come here, one still lives in Valley Walk, he’s 96, Dickie, 96 this year he was. And we would just go and put our shorts on and off we’d go - run, out to Harrow even, or wherever, do at least thirteen.

S: In the summer you’d run round the fields.

B: Oh yes, round the fields in the summer, yes. Go miles. We’d join Watford Joggers and that – girls had the Harriers, didn’t they? So my eldest daughter, she would run – she was a good runner, she would run and run. And she did get – like for England and that and she went and carried the torch

S: Jane carried the torch for

B: You know, at the Edinburgh Games they carried the Queen’s message and she carried it through the Watford bit. That was quite interesting, yes. So – my uncle, he was a runner and a swimmer, wasn’t he, and he swum the Channel, and he held the record from Dover to Deal, didn’t he, my uncle George?

S: Yes.

B: Yes, swimming. So I think it was my dad played football and was arunner – so I think it’s in the blood really, isn’t it? I still run today.

Int: When did you get married?

B: 1969.

Int: In Croxley?

B: Oh yes, up the church.

S: All Saints.

B: Yes. We wanted to get married when we was 18, but my Mum said ‘no, you’ve got to wait until you’re 21’ – which was the law then, I think, 21. ‘Wait till you’re 21’. Which, when I look back, it’s probably right really, because even at 21 we was – we didn’t really –

S: Green.

B: We didn’t really know.

S: Really. Green.

B: No. But I always remember we were never asked to get married, we were just together, all the time, weren’t we? Yes. So we just got married. (laughs)

Int: Were there any events stand out in your memory, local events like the Revels?

S: We always used to go to the Revels. It was lovely because they had the live procession then – of course not allowed now – and I danced round the maypole – oh yes.

Int: Right from when you were a little child did you do the maypole dancing?

S: Yes, yes. With the Brownies.

Int: So you belonged to the Brownies?

S: Yes, I did, yes.

Int: And then on to the Girl Guides?

S: Yes.

Int: And were there groups that met here in Croxley, were they local ones?

S: Oh yes. And my friend – she lived at Sarratt, but I used to go her meetings sometimes, and I remember her mum’s kitchen, it was a real old farmhouse kitchen, you know, with the fire – open – it was lovely and she lives in Croxley now, she didn’t get married, but we’ve always been friends and she taught – well, she was Brown Owl when Katy – the oldest one – went there.

Int: And where did you meet in Croxley for Brownies and Girl Guides?

S: Malvern Way.

Int: At the school?

S: Yes. And then sometimes at St. Oswald’s.

Int: And did you belong to Cubs and Scouts?

B: Scouts. Cubs, Scouts, yes.

Int: And where did they meet in Croxley?

B: Watford Road. 1st Croxley Green, we was. They had 1st and 2nd Croxley Green there, yes. Used to love it. Till I was about 15, probably 16 before I packed up the Scouts.

Int: When it became time to go to work?

B: Well, I was at work, yes. I’d come in then. But – yes, I loved the Scouts. We’d go camping, things like that, you know. We used to carry great big knives in the pack.

S: You know –with wood.

Int: Whittling?

S: Yes, fire.

B: We used to go camping down Chorleywood, we had an old go-cart, cart thing, with the chains on, and the younger boys would be on the chains and the older boys would be on the handles, so they could lift their feet up as they were going along. We’d go down to Chorleywood Camp and we’d stay there most weekends if we could. Just cooking, used to make a plum duff and things and all sorts down there. I loved Scouts.

Int: And when did you move to this house?

B: 1969?

S: 1969. We bought it before we – no, we didn’t buy it, we rented it before we got married. And my friend lived across there, and I said ‘Oh, I’d love to live in this road.

B: This house, you couldn’t see – it was like a jungle out here, you couldn’t see the front door, nor the back, could we?

S: No. Nine foot hedge it was, and you had a tree that went over. We came in dark, didn’t we, with a candle, I think, and a torch?

Int: How much did it cost when you bought it in 1969?

B: Well, we rented it.

S: For three years.

B: It wasn’t that much was it? What was the rent?

S: It was £25 a month to rent. And then it must have been 1972 we bought it. We said we’d pay the price, you know, otherwise I don’t think she would have sold it.

B: It belonged to King’s the sausage people of Watford.

S: They still owned some of the houses here. It had gone to their daughters’ daughters, you know.

B: Originally we was going to have a caravan, weren’t we?

S: We were.

B: Ten bob deposit on a caravan and lost it.

S: I hadn’t thought about getting to work, to Northwood, through Bushey, out that way. Never thought of that.

Int: And where did you work?

S: [Adey Boys] in Northwood, upholsterers. That’s what I did.

Int: And was that straight from when you left school?

S: Yes. Well, before I left school I used to – my friend, her uncle owned a shop, and I used to – think ‘Oh yes’. Because I liked sewing.

Int: How long did you work there?

S: Till I had the children. Six, seven years. Yes. Curtains, loose covers. Sewing carpets together. Because – you know, you didn’t buy a big carpet half the time, and you’d have to sew them.

Int: I can imagine it was very hard.

S: Enjoyable. You went into the big houses in Moor Park.

Int: Look round and see what it’s like. (laughter)

B: You’d see quite a few famous people – Roger Moore was it?

S: Roger Moore, yes. Made some curtains for him.

Int: Fascinating. Did you have anything to do with the Guildhouse when you were here?

B: I did, yes. I was a member there, and when it burned down. I used to do the Scout Show there, in the hall at the back. We used to do the Scout Show every year. I used to like that, yes. Because originally it was only the hall that burned, and then the Guildhouse was still there. Now you’ve got Dickinson’s over there.

S: They weren’t supposed to pull it down.

B: It was left to the people of Croxley and people who worked at Dickinson’s, so when they pulled it down they – there was like a little shed – over the playing fields, and so they had to change it to that. I still go there now, Dickinson’s, yes.

Int: Where’s that exactly?

B: Sports ground.

S: Over the fields.

B: Dickinson’s Sports Ground. You’ve got the Community – the field there, and the Club at the top is all Dickinson’s, belonged to Dickinson’s. They used to have all their things up there, didn’t they? Once a year, and shows, and they used to have the firemen at the Mill to the shows and that up there, you know, and they used to come out with the hose pipes and they hit a target, and as kids we’d stand behind the targets and get soaked!

Int: So how often did that happen?

B: Once a year. Yes, they used to have the firemen. But they used to have different competitions, so sometimes it would be over Apsley or Nash Mills, because they had quite a few different places and they would move around and have these competitions, yes. They were firemen. Fully trained.

Int: Why have you decided to stay in Croxley all this time? Ever considered living anywhere else?

S: I like Norfolk. Haven’t we?

B: We’ve been happy here, to be honest. We’re happy here really. Not so happy with some of the buildings that are going up at the moment. But then these were fields as well.

S: Farmer’s fields, weren’t they?

B: My mum’s council house was brand new when we moved in there, down Fuller Way, brand new.

S: They used to have the cows in the fields over there, didn’t they?

B: They did. I let them out, me and my friend did. The field where the school is now, we used to go and play in when we was kids. Well, there was a gate there, it was a farmer’s field really, and we opened the gate and the cows come out. And the fathers were trying to get the cows in with the forks, and one of the gentlemen, he was very small and this cow, he thought ‘no, you’re too small, mate, I’ll …’ And he chased him all the way down to the bottom of Fuller Way, yes, this cow did. And we as kids, we thought it was funny. But yes, we did let the cows out, but not on purpose, we just got through the gate, that’s where the farmer used to put his cattle. And then you had Stone’s Orchard at the back, which was all cherries and I’ve had a few cherries out of there in my time.

S: Because we had a big orchard where the library is now. There was a hairdresser’s and the rest of it was all trees, apples, pears, wasn’t there? Oh yes. Us went scrumping.

Int: Who did the orchard belong to?

B: Stones.

S: Stones’s son, yes.

B: Used to sell them on the Green – cherries and cobnuts, he used to sell there. And then you had – where’s that other place there with the big houses – Parrotts.

S: Parrotts, yes. And they used to roast a pig.

B: They used to open it up, Parrotts, and once a year they’d have a big do up there.

Int: And did you ever go to it?

B: Oh yes, yes.

Int: Was it open to the whole of Croxley?

B: Yes. There’s quite a few houses there, but at one time there was just one big house in there, on the Green.

S: Knocked down, isn’t it?

B: Yes, the house has gone, yes. We think [The One Show] star lives up there now.

Int: I have heard that, yes.

S: She goes out running, doesn’t she?

Int: So there was a big pig roast and just alcohol and games – just chatting?

B: Yes.

Int: And when did that finish?

B: Probably in the fifties, I suppose, fifties, sixties, yes.

S: But they still have the Revels. I’m not sure, is it on this year?

B: Yes. Oh yes. It’s a big thing now, isn’t it? It was only a little thing when we was kids.

S: Didn’t have any –

B: Big thing now.

S: - stalls or anything. It was just the arena and, you know –

Int: And did you have the maypole dancing?

S: Yes.

Int: What other kinds of things happened in the arena?

S: All sorts of dancing and musicians.

B: Plus they had the parade that went all round Croxley, didn’t it?

S: When we lived here. You know, all the parade went right round Croxley, it was lovely.

Int: Did you parade when you were at school? I think Harvey Road may have had -

B: All the schools had something.

Int: and the high schools, Durrants, did they parade?

B and S: Yes, oh yes.

B; All went up there, yes.

S: You had trampolines up there, didn’t they, and –

Int: And you’re probably too young to remember the 53 Coronation but do you remember the Silver Jubilee – were there any parties around here?

S: Oh, there was, yes.

B: We had a street party here.

Int: In Repton Way?

B: Oh yes.

S: And Margaret took some photos, yes. But I remember 53. Because my mum was the only one with a television, it was like that, a big box with a little – and half the street came in.

Int: And that was in Malvern Way?

S: Yes.

Int: So the whole of the street piled into your house to stare at the Coronation on your tv?

S: Yes.

Int: And you remember it? Watching it?

S: Bits of it, when I could see it. Yes.

B: Only little telly, see, 9 inch square.

S: 9 inch it was, yes.

Int: And your family had owned various businesses in Croxley as well, some of your family, Sheila?

S: Michael, my dad’s uncle, yes. He had a greengrocer’s in Croxley, yes.

Int: Which greengrocer’s was it?

S: Oh, Element’s the greengrocer’s. Yes.

B: Still had all the old boxes on it.

S: The old tiles and they wanted to make it modern, but she didn’t want that. It was the real old tiles – painted – you know, all blue. Yes. Had that for quite a while.

Int: And when you were growing up did your parents do all their shopping here in Croxley?

B & S: Yes, yes.

Int: Did you ever have to go down to Rickmansworth or into Watford for anything?

B & S: No, no.

Int: What about clothes – could you even buy clothes and shoes here?

S: Clothes, shoes – yes, anything. Wool, baby stuff.

Int: In the Co-op?

S: Yes. You had one big Co-op, and you had a butcher’s and you had a greengrocer’s then you had the little – where the funeral directors are – and that was with all the bits and pieces.

B: The butcher’s used to have the sawdust on the floor down there, and as boys we used to go in there and start kicking about – we used to kick the sawdust about because it was like being on the beach to us! (laughter) As boys.

S: My mum – you had Hunts store on Scots Hill and you had a garage up there.

Int: What did Hunts sell?

S: Oh. Groceries.

Int: Groceries.

S: On Monday she’d walk her list up there – from the school we used to go with her and she’d bring home – she’d probably have a Fray Bentos pie she’d buy for Monday’s dinner. And then they’d deliver it, didn’t they, in a van. You know, it’s always deliveries, deliveries have always gone on.

B: My mum went to Bonwit’s, Mr Bonwit’s up New Road. And we used to go there as kids and he’d have tins of broken biscuits, and we could have a broken biscuit. But mum used to get a list and then the boy would come up on a bike in the week and deliver it in a cardboard box on one of those big bike things.

Int: Didn’t have a car?

B: No.

Int: When did you get your first car?

B: What, here? Or my father? He never really had a car until very late on, did he?

Int: And you?

B: When I was about 18 or 19, probably, wasn’t it, about then, probably?

S: You did buy a car, but you took it out and the wheel fell off.

B: I did have one that the wheel fell off, yes. It was – we had three children so we had to get a car.

S: About ten months – we bought a little Mini off your brother, £50.

B: I did. Had it four years and sold it for £50. Can’t be bad, can it?!

S: We had no seat belts, of course. Turning a corner, holding Jane in the middle and Pauline. And you’d just tootle along.

B: Piled up on the top, no boot.

S: Yes, going on holiday.

Int: Where did you go on holiday?

S: Hayling. Clacton.

B: Hayling Island.

S: Hayling Island. I always used to love that.

B: Hayling Island, yes.

S: Every year we went there. Because my nan lived in Barton Way, on the corner of Winchester Way, her neighbour had a caravan, so he used to lend it – to sort of all the family, every year. Really nice.

Int: Did you ever go up to London? Anywhere, growing up?

S: Oh, we did, didn’t we? Went up there a lot when we were courting, yes, walking round.

B: Upstairs I have a picture of me and my two brothers in Trafalgar Square and the man trying to get a pigeon on each of our hands – we were in our school uniforms and short trousers, still got it upstairs somewhere. And I treasure that little photograph – we were in Trafalgar Square, and in them days they were trying to get the pigeons to stand on your hand, and there was a big crowd of people, all round, weren’t there? And I got a copy of it, you know, and kept it, because it had all people standing round in Trafalgar Square. Because they can’t do that now, can they?

S: No, you’re not allowed.

B: They had the little brown trains then. Shut, bang.

S: Windows, and you had to pull them – a leather strap.

B: One of my brothers he went down to use the toilet by the train. The train pulled in and in they got, and they went all the way – they had their cowboy uniforms on – and they went all the way to Baker Street.

S: What were they, six?

B: And when they got to Baker Street they didn’t know what to do. So in the end they got picked up and brought them back, all the way back, these two boys, in the guard’s wagon. And my dad still had to pay for them travelling up and down, yes. Him and his mate, wasn’t it? In their cowboy uniforms. Because there were a lot of bang doors, so you could just get into a little cabin. Parcel thing on top. So that’s what they done, yes, mischief. Boys – muck about.

Int: Oh, it’s so interesting, thank you for sharing all your memories.

B: Oh, loads of things really. I mean, we used to go down the canal fishing, the barges down there as well, I remember the barges. We used to go and play with the lads down there on the barges. They used to bring all the pulp up, and the coal.

S: And in the winter the canal used to freeze over, and you could skate on it.

B: Walk across it.

S: My dad used to take his bike down Mill Hill and go across – only about two feet deep, wasn’t it? That’s the winters we used to have.

B: It was banned from the canal, but we still used to go down there.

Int: Why were you banned from the canal?

B: Oh, because it was dangerous, wasn’t it?

Int: Oh, when it was iced over.

B: Well, in them days the boys would go on the bridge there – you know – dive in. You wouldn’t do that now, children.

S: He pulled a boy out once, didn’t you?

B: Yes, I did – going to work. I was going to work and I could hear ‘help, help!’ so I walked down and there was this boy he was clinging – by the bridge there and he was clinging on to the rocks by the side, the wall, but he couldn’t get out. Pulled him out, I carried him all the way along to the gate, gatehouse, and I went to work. Never heard no more.

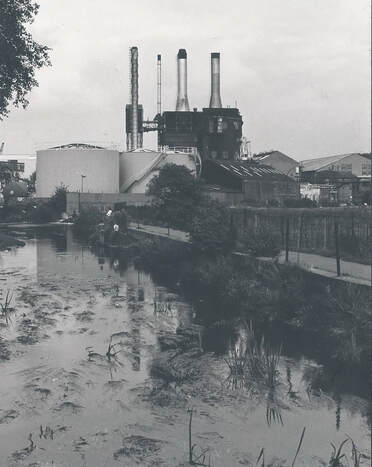

Int: Did the Mill cause quite a lot of pollution in the river?

B: It used to be white, that River Gade was white, it used to be white.

Int: Foam from the effluent from?

B: Yes, the starch and that. But the fish used to love it. They would eat it. The water was warm, you see, coming out from the mill.

S: We used to go paddling in it.

B: Yes. There used to be a little stream, wasn’t there, which you know, some of us would go down there, like being down the River Chess.

S: Not allowed now.

B: Well, the River Chess has been polluted a couple of times now, hasn’t it? That was our holidays, really.

S: Yes, it was. Some holidays down there.

B: And this little stream, from the canal, would overflow and then go into the River Gade there. That was where we would paddle and muck about, with the nets, you know, the little fishing nets. Or jam jars.

S: Simple things.

Int: So what do you think of – good things that have changed in Croxley over the years? And maybe not such good things that have changed?

S: Buildings.

Int: Too many?

S: Too many. Too many.

B: Oh we don’t like that big tall thing. Unfortunately.

Int: I don’t think anybody does!

B: We don’t mind them being there because

S: We don’t mind it – but you can’t see it from Watford.

B: No. So we don’t like that. We’re not happy about the build up there, but then again I look back and I think well, this was a field. Yes, that farmer, I worked for him as a boy. 12 bob. 12 bob. Pick the ‘taters. Mr. Foster his name was. Two days picking the potatoes up and at the end he would give you cabbages and I thought ‘cor, what a prize!’ Brought this cabbage home to my mum, you know.

Int: How old were you then?

B: Don’t know. Maybe eight, nine maybe. Yes. Used to do a paper round, milk round, and work up there as well. Turnips – we used to cut and tie them – but the potatoes, you’d do a section and the tractor would come along, turn the ‘taters over and then you’d pick your section. But you’d just about finish your section and he’d come back again. That was the farm, Mr. Foster, yes.

Int: And that was at Killingdown Farm, you did all this?

B: Yes. On the back of a tractor – go out in the fields.

Int: It was like summer jobs that you did in summer?

B: Yes, or in autumn, whatever. School holidays, any time. Yes. The paper round was 16 bob a week – that was at Moxley’s, and the milkman, I forget what he paid me.

S: Sixteen shillings – how much is that now?

B: Not much. But don’t forget – I mean, down at the mills, only £9 a week.

S: Yes, I used to live on a fiver a week.

B: When we bought this house, I was only earning £20 a week. You think – cor blimey!

Int: How did you live on £20 a week?

S: Oh well, I earned £5 and that lasted you a week to buy everything.

Int: And that’s what you earned at the upholsterer’s?

B: Yes.

Int: And you earned £20 a week?

B: I did when I was about 18, 19, when I got onto the guillotines and that.

S: No, you were about 21 then.

B: When I went down there it was £3 a week, to begin with. Yes. ‘Got a job, mister?’

Int: And when the mill closed in 1980?

B: I was on good money.

Int: You were on good money. And what did you do after that?

B: I was fishing down by the river, and one of my friends walked along and I said ‘where are you going, Dave?’ and he said ‘they’re starting people down at the mill clearing up’. So I went down there, didn’t I, with this bloke, followed him down, I thought ‘I’m going to have some of that’. And it was an agency and they employed you to clear up. I mean it was running the guillotines and everything as normal, and as one would close down they would be sold off and go – got less and less. So I just got my unemployment money and that from the mill, and then the bloke said to us ‘we’re going to take you on to Nash Mills’. And I thought ‘this is good, I’ve got unemployment money and I’ve got another job’. But then the Union found out that we was working down there and they were running work in Scotland, they were running there, that was another Dickinson’s place, and so they shut it down, didn’t they?

S: Yes.

B: Yes. So then we had a little treat, because I think I got £6000 from the mill. So we went to America. Took the kids to Disney World. I didn’t tell her, I just went down and booked it and I said ‘we’re going to –‘ . In February, wasn’t it? And we went to America.

S: Yes.

B: Never been in my life – hadn’t even been abroad, had we? £6000 was a lot of money then.

Int: And that was sort of your redundancy payment?

B: Yes, yes. And I got a pension out of that, which I kept, I still get the pension today. It’s a funny pension, really. It pays me, what, £40 – still pays me forty something a month now doesn’t it? But the Government takes £8 of it, every month off – it’s a lot of money really, and I don’t know – it was called a House of Dickinson’s, and you didn’t have to pay for it, so I can’t complain really.

Int: They looked after their employees.

B: Yes. A lot of people cashed them in, but I kept mine. And they still pay me out now. I know it don’t seem much now, but –

S: You did at the time!

B: So I still get my old pension, yes.

Int: So Dickinson’s Mills was a good company to work for?

B: They were, yes.

Int: Really looked after you people.

B: And it’s one of the few pensions that - when I was to die tomorrow, she would get that pension, or you can designate your eldest child. To take that pension. So – most of them, they die with you, don’t they, pensions nowadays? That one still goes, yes. So it’s not a lot of money, but it was all free, through Dickinson’s. They were a good company. Yes. You get your teeth done cheaply, didn’t you, Sheila?

S: Yes. And the glasses.

B: And glasses.

Int: That’s worth a lot.

B: Yes. Down there.

S: HSA it was called.

Int: That’s quite progressive for the sixties and seventies today – glasses and teeth all from your company.

B & S: Yes.

B: And they used to have a Christmas party every year down at the Guildhouse. The women used to do it, they used to collect money every week, sell raffle tickets, they used to come round with tea, great big jugs of tea, and they would sell you a ticket as well. And one year they got fed up with the Christmas party, they thought they’d try go Wembley, to see the ice skating, pantomime. So they had three coaches that went down to Wembley, and when they come to go out, they’d only got enough for one – all the kids had gone into the town, all sneaked out. (laughter). I think the reason they changed it because they used to throw jelly and ice cream about, I think. (laughter). You know, when Father Christmas came in, he got covered in ice creams. People don’t have ice cream now, do they? Children. Macdonalds they want to.

S: Born in Macdonalds.

B: But we had – I think that was why they changed it. And they went down, and they lost half the children. But my friend I knew, he said it was two o’clock before they got home from Wembley because the children were gone. The older ones, they’d gone into Wembley for the night. Didn’t want to watch the pantomime. Skating – I think it was panto on ice, wasn’t it, something like that they used to do there? Yes. Dickinson’s had a system, that as long as you got on and done your work they would move you on, so as you moved on you’d get a better machine, or whatever. And it was quite good money. I used to work 6 to 2, 2 to 10. And twelve hour days and twelve hour nights. And then to help pay the mortgage I used to do four nights and I’d finish Friday morning, wouldn’t I? Friday morning, I’d come home at 6, I’d go to bed and I’d go back to work at 2, and do 2-10 Friday, so then I could get Saturday and Sunday in. So that was how we’d pay for the mortgage.

Int: You deserved the holiday in America!

B: Used to get two weeks a year then, in those days. Never got New Year’s Day or anything like that.

S: Free. You could go anywhere, no worries, ride your bike down the lane. It was so simple. You didn’t have to go to Watford, because everything was here, everything you could think of. Yes, very free. Long skate down the roads because there was no cars.

B: Used to race down this road, didn’t we? Used to make box carts and race down there, as kids, yes, and roller skate down. We’d have a different craze each month. You wouldn’t see the car, you see, very rare, the odd one, but you could come down. We’d have a game of football in the street as boys. That wouldn’t worry you. Changed, hasn’t it?

Int: Which school did you go to, Sheila?

S: Malvern Way.

Int: OK, of course.

S: Green Lane, Durrants.

Int: Yes. Happy memories of school?

S: Didn’t like Malvern Way. The headmistress, Miss Hemmings, was really terrible, not being awful, but – and when later on, I think I was about twelve, we went on holiday to the Isle of Wight and we was sitting at the table and another couple with their son, and “Oh, we used to live in Croxley.” And she said “Yes, and he used to come home with his hankie soaking wet, he’d push it in his mouth because Miss Hemmings wouldn’t have any coughing or anything”. And I went “oh”.

Int: A tyrant.

S: Yes. I liked Little Green, that was lovely, and Durrants. Which is no more. That was a lovely school.

Int: You probably walked to school?

S: Oh yes. And in the winter you had to wear masks because of the smog, and if it was in the winter they let us out of school early because it was getting dark and you couldn’t see.

B: The smog, you couldn’t see across the road in the smog.

Int: I’m surprised, you know. I’ve always known about the London smogs but I didn’t realise you had smogs here as well.

B: Oh yes, yes, yes. We had them here, yes.

S: You had to listen for the traffic.

B: Yes. If you didn’t have your mask on the lady who saw you across the road would tell you off.

S: Get your mask. It’s come back to that – where’s your mask?

Int: And what kind of a mask was it?

B: Just what you’ve got now, really.

S: Yes.

Int: And where did you go to school?

B: I went to Yorke Road School, Old Boys School, Harvey Road and then to Durrants here. Yes. Miss Bridge was headmistress at Yorke Road and then was Mrs. Higby was headmistress at Old Boys School and then Harvey Road was Mr. Ford, and Durrants was Mr Jefferies, wasn’t he? Yes, I know him because he gave me a good hiding. (laughter). Give me the cane, he did, a couple of times, yes.

Int: Why did you move from Yorke Road to Old Boys to Harvey Road?

B: Well, that was the system.

Int: That was the sequence.

B: Yes. I think Harvey Road then was an early school and so you went to Yorke Road and then you moved, went to Old Boys School and then from there we went into Harvey Road, which was like chalet things there really. Mr. Ford was also my Sunday School teacher, Baptist Church. So that’s where we went. And that’s where we met, at Durrants we met.

S: He sat behind me.

Int: In which subject?

S: All.

B: All.

Int: You stayed in your form going from subject to subject. Any subjects you particularly enjoyed at Durrants, any teachers you particularly liked or disliked?

S: Mr Jefferies, he was really strict, the headmaster. If you was walking past his office and you even spoke, he’d be out there, put his mortar on ”No noise!”

B: With the mortar on the head, you knew ‘oh, going to get the cane now’.

Int: Was there a lot of corporal punishment?

B: Yes. We had one teacher, he would stand – if he was going to give the cane, he would stand on the chair and as he would jump off the chair so he would bring the stick down, and one day he stood on the chair and the stick went through the ceiling and all the class laughed so he hit all the class. They wouldn’t dare do that now, would they? No. So we all got the cane, yes. They would throw anything at you, wouldn’t they, the masters? We weren’t always innocent but, you know ...

S: The blackboard brushes.

B: A ruler, they used to hit you. Yes.

S: Didn’t do us any harm, though, did it?

B: Not really, no.

S: No.

Int: Were you keen on the sports at school?

B: That’s what I liked. I did like that, yes. I wasn’t very good at football and that sort of thing, but because I played football and I found that if you had a bad game everyone would moan at you – ‘oh go on’ – and so I thought ‘no, this ain’t for me’. Anyway I enjoyed running, I was a good runner even at school. It didn’t matter – with running it doesn’t matter if you’re first, last, it’s only yourself, isn’t it? So that’s why I run. I run at school, yes. I loved it, loved running.

Int: And you kept running?

B: Yes. Virtually I did, yes. Even when I was down at work I would come home, put my shorts on and go and run thirteen miles before I had my dinner, wouldn’t I?

Int: Where did you go?

B: Anywhere. I had friends who would come here, one still lives in Valley Walk, he’s 96, Dickie, 96 this year he was. And we would just go and put our shorts on and off we’d go - run, out to Harrow even, or wherever, do at least thirteen.

S: In the summer you’d run round the fields.

B: Oh yes, round the fields in the summer, yes. Go miles. We’d join Watford Joggers and that – girls had the Harriers, didn’t they? So my eldest daughter, she would run – she was a good runner, she would run and run. And she did get – like for England and that and she went and carried the torch

S: Jane carried the torch for

B: You know, at the Edinburgh Games they carried the Queen’s message and she carried it through the Watford bit. That was quite interesting, yes. So – my uncle, he was a runner and a swimmer, wasn’t he, and he swum the Channel, and he held the record from Dover to Deal, didn’t he, my uncle George?

S: Yes.

B: Yes, swimming. So I think it was my dad played football and was arunner – so I think it’s in the blood really, isn’t it? I still run today.

Int: When did you get married?

B: 1969.

Int: In Croxley?

B: Oh yes, up the church.

S: All Saints.

B: Yes. We wanted to get married when we was 18, but my Mum said ‘no, you’ve got to wait until you’re 21’ – which was the law then, I think, 21. ‘Wait till you’re 21’. Which, when I look back, it’s probably right really, because even at 21 we was – we didn’t really –

S: Green.

B: We didn’t really know.

S: Really. Green.

B: No. But I always remember we were never asked to get married, we were just together, all the time, weren’t we? Yes. So we just got married. (laughs)

Int: Were there any events stand out in your memory, local events like the Revels?

S: We always used to go to the Revels. It was lovely because they had the live procession then – of course not allowed now – and I danced round the maypole – oh yes.

Int: Right from when you were a little child did you do the maypole dancing?

S: Yes, yes. With the Brownies.

Int: So you belonged to the Brownies?

S: Yes, I did, yes.

Int: And then on to the Girl Guides?

S: Yes.

Int: And were there groups that met here in Croxley, were they local ones?

S: Oh yes. And my friend – she lived at Sarratt, but I used to go her meetings sometimes, and I remember her mum’s kitchen, it was a real old farmhouse kitchen, you know, with the fire – open – it was lovely and she lives in Croxley now, she didn’t get married, but we’ve always been friends and she taught – well, she was Brown Owl when Katy – the oldest one – went there.

Int: And where did you meet in Croxley for Brownies and Girl Guides?

S: Malvern Way.

Int: At the school?

S: Yes. And then sometimes at St. Oswald’s.

Int: And did you belong to Cubs and Scouts?

B: Scouts. Cubs, Scouts, yes.

Int: And where did they meet in Croxley?

B: Watford Road. 1st Croxley Green, we was. They had 1st and 2nd Croxley Green there, yes. Used to love it. Till I was about 15, probably 16 before I packed up the Scouts.

Int: When it became time to go to work?

B: Well, I was at work, yes. I’d come in then. But – yes, I loved the Scouts. We’d go camping, things like that, you know. We used to carry great big knives in the pack.

S: You know –with wood.

Int: Whittling?

S: Yes, fire.

B: We used to go camping down Chorleywood, we had an old go-cart, cart thing, with the chains on, and the younger boys would be on the chains and the older boys would be on the handles, so they could lift their feet up as they were going along. We’d go down to Chorleywood Camp and we’d stay there most weekends if we could. Just cooking, used to make a plum duff and things and all sorts down there. I loved Scouts.

Int: And when did you move to this house?

B: 1969?

S: 1969. We bought it before we – no, we didn’t buy it, we rented it before we got married. And my friend lived across there, and I said ‘Oh, I’d love to live in this road.

B: This house, you couldn’t see – it was like a jungle out here, you couldn’t see the front door, nor the back, could we?

S: No. Nine foot hedge it was, and you had a tree that went over. We came in dark, didn’t we, with a candle, I think, and a torch?

Int: How much did it cost when you bought it in 1969?

B: Well, we rented it.

S: For three years.

B: It wasn’t that much was it? What was the rent?

S: It was £25 a month to rent. And then it must have been 1972 we bought it. We said we’d pay the price, you know, otherwise I don’t think she would have sold it.

B: It belonged to King’s the sausage people of Watford.

S: They still owned some of the houses here. It had gone to their daughters’ daughters, you know.

B: Originally we was going to have a caravan, weren’t we?

S: We were.

B: Ten bob deposit on a caravan and lost it.

S: I hadn’t thought about getting to work, to Northwood, through Bushey, out that way. Never thought of that.

Int: And where did you work?

S: [Adey Boys] in Northwood, upholsterers. That’s what I did.

Int: And was that straight from when you left school?

S: Yes. Well, before I left school I used to – my friend, her uncle owned a shop, and I used to – think ‘Oh yes’. Because I liked sewing.

Int: How long did you work there?

S: Till I had the children. Six, seven years. Yes. Curtains, loose covers. Sewing carpets together. Because – you know, you didn’t buy a big carpet half the time, and you’d have to sew them.

Int: I can imagine it was very hard.

S: Enjoyable. You went into the big houses in Moor Park.

Int: Look round and see what it’s like. (laughter)

B: You’d see quite a few famous people – Roger Moore was it?

S: Roger Moore, yes. Made some curtains for him.

Int: Fascinating. Did you have anything to do with the Guildhouse when you were here?

B: I did, yes. I was a member there, and when it burned down. I used to do the Scout Show there, in the hall at the back. We used to do the Scout Show every year. I used to like that, yes. Because originally it was only the hall that burned, and then the Guildhouse was still there. Now you’ve got Dickinson’s over there.

S: They weren’t supposed to pull it down.

B: It was left to the people of Croxley and people who worked at Dickinson’s, so when they pulled it down they – there was like a little shed – over the playing fields, and so they had to change it to that. I still go there now, Dickinson’s, yes.

Int: Where’s that exactly?

B: Sports ground.

S: Over the fields.

B: Dickinson’s Sports Ground. You’ve got the Community – the field there, and the Club at the top is all Dickinson’s, belonged to Dickinson’s. They used to have all their things up there, didn’t they? Once a year, and shows, and they used to have the firemen at the Mill to the shows and that up there, you know, and they used to come out with the hose pipes and they hit a target, and as kids we’d stand behind the targets and get soaked!

Int: So how often did that happen?

B: Once a year. Yes, they used to have the firemen. But they used to have different competitions, so sometimes it would be over Apsley or Nash Mills, because they had quite a few different places and they would move around and have these competitions, yes. They were firemen. Fully trained.

Int: Why have you decided to stay in Croxley all this time? Ever considered living anywhere else?

S: I like Norfolk. Haven’t we?

B: We’ve been happy here, to be honest. We’re happy here really. Not so happy with some of the buildings that are going up at the moment. But then these were fields as well.

S: Farmer’s fields, weren’t they?

B: My mum’s council house was brand new when we moved in there, down Fuller Way, brand new.

S: They used to have the cows in the fields over there, didn’t they?

B: They did. I let them out, me and my friend did. The field where the school is now, we used to go and play in when we was kids. Well, there was a gate there, it was a farmer’s field really, and we opened the gate and the cows come out. And the fathers were trying to get the cows in with the forks, and one of the gentlemen, he was very small and this cow, he thought ‘no, you’re too small, mate, I’ll …’ And he chased him all the way down to the bottom of Fuller Way, yes, this cow did. And we as kids, we thought it was funny. But yes, we did let the cows out, but not on purpose, we just got through the gate, that’s where the farmer used to put his cattle. And then you had Stone’s Orchard at the back, which was all cherries and I’ve had a few cherries out of there in my time.

S: Because we had a big orchard where the library is now. There was a hairdresser’s and the rest of it was all trees, apples, pears, wasn’t there? Oh yes. Us went scrumping.

Int: Who did the orchard belong to?

B: Stones.

S: Stones’s son, yes.

B: Used to sell them on the Green – cherries and cobnuts, he used to sell there. And then you had – where’s that other place there with the big houses – Parrotts.

S: Parrotts, yes. And they used to roast a pig.

B: They used to open it up, Parrotts, and once a year they’d have a big do up there.

Int: And did you ever go to it?

B: Oh yes, yes.

Int: Was it open to the whole of Croxley?

B: Yes. There’s quite a few houses there, but at one time there was just one big house in there, on the Green.

S: Knocked down, isn’t it?

B: Yes, the house has gone, yes. We think [The One Show] star lives up there now.

Int: I have heard that, yes.

S: She goes out running, doesn’t she?

Int: So there was a big pig roast and just alcohol and games – just chatting?

B: Yes.

Int: And when did that finish?

B: Probably in the fifties, I suppose, fifties, sixties, yes.

S: But they still have the Revels. I’m not sure, is it on this year?

B: Yes. Oh yes. It’s a big thing now, isn’t it? It was only a little thing when we was kids.

S: Didn’t have any –

B: Big thing now.

S: - stalls or anything. It was just the arena and, you know –

Int: And did you have the maypole dancing?

S: Yes.

Int: What other kinds of things happened in the arena?

S: All sorts of dancing and musicians.

B: Plus they had the parade that went all round Croxley, didn’t it?

S: When we lived here. You know, all the parade went right round Croxley, it was lovely.

Int: Did you parade when you were at school? I think Harvey Road may have had -

B: All the schools had something.

Int: and the high schools, Durrants, did they parade?

B and S: Yes, oh yes.

B; All went up there, yes.

S: You had trampolines up there, didn’t they, and –

Int: And you’re probably too young to remember the 53 Coronation but do you remember the Silver Jubilee – were there any parties around here?

S: Oh, there was, yes.

B: We had a street party here.

Int: In Repton Way?

B: Oh yes.

S: And Margaret took some photos, yes. But I remember 53. Because my mum was the only one with a television, it was like that, a big box with a little – and half the street came in.

Int: And that was in Malvern Way?

S: Yes.

Int: So the whole of the street piled into your house to stare at the Coronation on your tv?

S: Yes.

Int: And you remember it? Watching it?

S: Bits of it, when I could see it. Yes.

B: Only little telly, see, 9 inch square.

S: 9 inch it was, yes.

Int: And your family had owned various businesses in Croxley as well, some of your family, Sheila?

S: Michael, my dad’s uncle, yes. He had a greengrocer’s in Croxley, yes.

Int: Which greengrocer’s was it?

S: Oh, Element’s the greengrocer’s. Yes.

B: Still had all the old boxes on it.

S: The old tiles and they wanted to make it modern, but she didn’t want that. It was the real old tiles – painted – you know, all blue. Yes. Had that for quite a while.

Int: And when you were growing up did your parents do all their shopping here in Croxley?

B & S: Yes, yes.

Int: Did you ever have to go down to Rickmansworth or into Watford for anything?

B & S: No, no.

Int: What about clothes – could you even buy clothes and shoes here?

S: Clothes, shoes – yes, anything. Wool, baby stuff.

Int: In the Co-op?

S: Yes. You had one big Co-op, and you had a butcher’s and you had a greengrocer’s then you had the little – where the funeral directors are – and that was with all the bits and pieces.

B: The butcher’s used to have the sawdust on the floor down there, and as boys we used to go in there and start kicking about – we used to kick the sawdust about because it was like being on the beach to us! (laughter) As boys.

S: My mum – you had Hunts store on Scots Hill and you had a garage up there.

Int: What did Hunts sell?

S: Oh. Groceries.

Int: Groceries.

S: On Monday she’d walk her list up there – from the school we used to go with her and she’d bring home – she’d probably have a Fray Bentos pie she’d buy for Monday’s dinner. And then they’d deliver it, didn’t they, in a van. You know, it’s always deliveries, deliveries have always gone on.

B: My mum went to Bonwit’s, Mr Bonwit’s up New Road. And we used to go there as kids and he’d have tins of broken biscuits, and we could have a broken biscuit. But mum used to get a list and then the boy would come up on a bike in the week and deliver it in a cardboard box on one of those big bike things.

Int: Didn’t have a car?

B: No.

Int: When did you get your first car?

B: What, here? Or my father? He never really had a car until very late on, did he?

Int: And you?

B: When I was about 18 or 19, probably, wasn’t it, about then, probably?

S: You did buy a car, but you took it out and the wheel fell off.

B: I did have one that the wheel fell off, yes. It was – we had three children so we had to get a car.

S: About ten months – we bought a little Mini off your brother, £50.

B: I did. Had it four years and sold it for £50. Can’t be bad, can it?!

S: We had no seat belts, of course. Turning a corner, holding Jane in the middle and Pauline. And you’d just tootle along.

B: Piled up on the top, no boot.

S: Yes, going on holiday.

Int: Where did you go on holiday?

S: Hayling. Clacton.

B: Hayling Island.

S: Hayling Island. I always used to love that.

B: Hayling Island, yes.

S: Every year we went there. Because my nan lived in Barton Way, on the corner of Winchester Way, her neighbour had a caravan, so he used to lend it – to sort of all the family, every year. Really nice.

Int: Did you ever go up to London? Anywhere, growing up?

S: Oh, we did, didn’t we? Went up there a lot when we were courting, yes, walking round.

B: Upstairs I have a picture of me and my two brothers in Trafalgar Square and the man trying to get a pigeon on each of our hands – we were in our school uniforms and short trousers, still got it upstairs somewhere. And I treasure that little photograph – we were in Trafalgar Square, and in them days they were trying to get the pigeons to stand on your hand, and there was a big crowd of people, all round, weren’t there? And I got a copy of it, you know, and kept it, because it had all people standing round in Trafalgar Square. Because they can’t do that now, can they?

S: No, you’re not allowed.

B: They had the little brown trains then. Shut, bang.

S: Windows, and you had to pull them – a leather strap.

B: One of my brothers he went down to use the toilet by the train. The train pulled in and in they got, and they went all the way – they had their cowboy uniforms on – and they went all the way to Baker Street.

S: What were they, six?

B: And when they got to Baker Street they didn’t know what to do. So in the end they got picked up and brought them back, all the way back, these two boys, in the guard’s wagon. And my dad still had to pay for them travelling up and down, yes. Him and his mate, wasn’t it? In their cowboy uniforms. Because there were a lot of bang doors, so you could just get into a little cabin. Parcel thing on top. So that’s what they done, yes, mischief. Boys – muck about.

Int: Oh, it’s so interesting, thank you for sharing all your memories.

B: Oh, loads of things really. I mean, we used to go down the canal fishing, the barges down there as well, I remember the barges. We used to go and play with the lads down there on the barges. They used to bring all the pulp up, and the coal.

S: And in the winter the canal used to freeze over, and you could skate on it.

B: Walk across it.

S: My dad used to take his bike down Mill Hill and go across – only about two feet deep, wasn’t it? That’s the winters we used to have.

B: It was banned from the canal, but we still used to go down there.

Int: Why were you banned from the canal?

B: Oh, because it was dangerous, wasn’t it?

Int: Oh, when it was iced over.

B: Well, in them days the boys would go on the bridge there – you know – dive in. You wouldn’t do that now, children.

S: He pulled a boy out once, didn’t you?

B: Yes, I did – going to work. I was going to work and I could hear ‘help, help!’ so I walked down and there was this boy he was clinging – by the bridge there and he was clinging on to the rocks by the side, the wall, but he couldn’t get out. Pulled him out, I carried him all the way along to the gate, gatehouse, and I went to work. Never heard no more.

Int: Did the Mill cause quite a lot of pollution in the river?

B: It used to be white, that River Gade was white, it used to be white.

Int: Foam from the effluent from?

B: Yes, the starch and that. But the fish used to love it. They would eat it. The water was warm, you see, coming out from the mill.

S: We used to go paddling in it.

B: Yes. There used to be a little stream, wasn’t there, which you know, some of us would go down there, like being down the River Chess.

S: Not allowed now.

B: Well, the River Chess has been polluted a couple of times now, hasn’t it? That was our holidays, really.

S: Yes, it was. Some holidays down there.

B: And this little stream, from the canal, would overflow and then go into the River Gade there. That was where we would paddle and muck about, with the nets, you know, the little fishing nets. Or jam jars.

S: Simple things.

Int: So what do you think of – good things that have changed in Croxley over the years? And maybe not such good things that have changed?

S: Buildings.

Int: Too many?

S: Too many. Too many.

B: Oh we don’t like that big tall thing. Unfortunately.

Int: I don’t think anybody does!

B: We don’t mind them being there because

S: We don’t mind it – but you can’t see it from Watford.

B: No. So we don’t like that. We’re not happy about the build up there, but then again I look back and I think well, this was a field. Yes, that farmer, I worked for him as a boy. 12 bob. 12 bob. Pick the ‘taters. Mr. Foster his name was. Two days picking the potatoes up and at the end he would give you cabbages and I thought ‘cor, what a prize!’ Brought this cabbage home to my mum, you know.

Int: How old were you then?

B: Don’t know. Maybe eight, nine maybe. Yes. Used to do a paper round, milk round, and work up there as well. Turnips – we used to cut and tie them – but the potatoes, you’d do a section and the tractor would come along, turn the ‘taters over and then you’d pick your section. But you’d just about finish your section and he’d come back again. That was the farm, Mr. Foster, yes.

Int: And that was at Killingdown Farm, you did all this?

B: Yes. On the back of a tractor – go out in the fields.

Int: It was like summer jobs that you did in summer?

B: Yes, or in autumn, whatever. School holidays, any time. Yes. The paper round was 16 bob a week – that was at Moxley’s, and the milkman, I forget what he paid me.

S: Sixteen shillings – how much is that now?

B: Not much. But don’t forget – I mean, down at the mills, only £9 a week.

S: Yes, I used to live on a fiver a week.

B: When we bought this house, I was only earning £20 a week. You think – cor blimey!

Int: How did you live on £20 a week?

S: Oh well, I earned £5 and that lasted you a week to buy everything.

Int: And that’s what you earned at the upholsterer’s?

B: Yes.

Int: And you earned £20 a week?

B: I did when I was about 18, 19, when I got onto the guillotines and that.

S: No, you were about 21 then.

B: When I went down there it was £3 a week, to begin with. Yes. ‘Got a job, mister?’

Int: And when the mill closed in 1980?

B: I was on good money.

Int: You were on good money. And what did you do after that?

B: I was fishing down by the river, and one of my friends walked along and I said ‘where are you going, Dave?’ and he said ‘they’re starting people down at the mill clearing up’. So I went down there, didn’t I, with this bloke, followed him down, I thought ‘I’m going to have some of that’. And it was an agency and they employed you to clear up. I mean it was running the guillotines and everything as normal, and as one would close down they would be sold off and go – got less and less. So I just got my unemployment money and that from the mill, and then the bloke said to us ‘we’re going to take you on to Nash Mills’. And I thought ‘this is good, I’ve got unemployment money and I’ve got another job’. But then the Union found out that we was working down there and they were running work in Scotland, they were running there, that was another Dickinson’s place, and so they shut it down, didn’t they?

S: Yes.

B: Yes. So then we had a little treat, because I think I got £6000 from the mill. So we went to America. Took the kids to Disney World. I didn’t tell her, I just went down and booked it and I said ‘we’re going to –‘ . In February, wasn’t it? And we went to America.

S: Yes.

B: Never been in my life – hadn’t even been abroad, had we? £6000 was a lot of money then.

Int: And that was sort of your redundancy payment?

B: Yes, yes. And I got a pension out of that, which I kept, I still get the pension today. It’s a funny pension, really. It pays me, what, £40 – still pays me forty something a month now doesn’t it? But the Government takes £8 of it, every month off – it’s a lot of money really, and I don’t know – it was called a House of Dickinson’s, and you didn’t have to pay for it, so I can’t complain really.

Int: They looked after their employees.

B: Yes. A lot of people cashed them in, but I kept mine. And they still pay me out now. I know it don’t seem much now, but –

S: You did at the time!

B: So I still get my old pension, yes.

Int: So Dickinson’s Mills was a good company to work for?

B: They were, yes.

Int: Really looked after you people.

B: And it’s one of the few pensions that - when I was to die tomorrow, she would get that pension, or you can designate your eldest child. To take that pension. So – most of them, they die with you, don’t they, pensions nowadays? That one still goes, yes. So it’s not a lot of money, but it was all free, through Dickinson’s. They were a good company. Yes. You get your teeth done cheaply, didn’t you, Sheila?

S: Yes. And the glasses.

B: And glasses.

Int: That’s worth a lot.

B: Yes. Down there.

S: HSA it was called.

Int: That’s quite progressive for the sixties and seventies today – glasses and teeth all from your company.

B & S: Yes.

B: And they used to have a Christmas party every year down at the Guildhouse. The women used to do it, they used to collect money every week, sell raffle tickets, they used to come round with tea, great big jugs of tea, and they would sell you a ticket as well. And one year they got fed up with the Christmas party, they thought they’d try go Wembley, to see the ice skating, pantomime. So they had three coaches that went down to Wembley, and when they come to go out, they’d only got enough for one – all the kids had gone into the town, all sneaked out. (laughter). I think the reason they changed it because they used to throw jelly and ice cream about, I think. (laughter). You know, when Father Christmas came in, he got covered in ice creams. People don’t have ice cream now, do they? Children. Macdonalds they want to.

S: Born in Macdonalds.

B: But we had – I think that was why they changed it. And they went down, and they lost half the children. But my friend I knew, he said it was two o’clock before they got home from Wembley because the children were gone. The older ones, they’d gone into Wembley for the night. Didn’t want to watch the pantomime. Skating – I think it was panto on ice, wasn’t it, something like that they used to do there? Yes. Dickinson’s had a system, that as long as you got on and done your work they would move you on, so as you moved on you’d get a better machine, or whatever. And it was quite good money. I used to work 6 to 2, 2 to 10. And twelve hour days and twelve hour nights. And then to help pay the mortgage I used to do four nights and I’d finish Friday morning, wouldn’t I? Friday morning, I’d come home at 6, I’d go to bed and I’d go back to work at 2, and do 2-10 Friday, so then I could get Saturday and Sunday in. So that was how we’d pay for the mortgage.

Int: You deserved the holiday in America!

B: Used to get two weeks a year then, in those days. Never got New Year’s Day or anything like that.

Int: So you had to work New Year’s Day?

B: Yes, always, yes. Until the law changed. We only had two days. We used to have Christmas Day and Boxing Day, the next day then we’d start. We used to have two weeks, they’d shut a year. But they would shut the machines down, then. Because it cost them so much to start them up, because they were massive – you couldn’t believe how big they were.

S: They had the old chimney, down the mill, and if they shut the machines down, see all the – and my dad said ‘oh, they’ve had to shut the machines down’ because all the

Int: Stopped seeing the smoke coming out of the chimney.

S: Yes.

B: It was that vast we had a train used to go through the middle when I first as a boy, used to go through the cold mill, as they called it, the cold mills, the train used to go through with the coal or whatever was on it. You can’t imagine the train coming through the middle, but it did.

Int: So how – where Bywaters is today and the big business, all the complex of Croxley Business Centre, that was all the mill?

B: Yes, it stretched from Croxley Moor right through to nearly where the Sun is – yes – Morrison’s, sort of that area. That was all completely the mill. A lot of it was the waste, that was big white stuff, I think they made egg boxes out of it or something, the waste. Because when the machines was running such a speed they would never stop, so when they had a break, if they had a break in the paper, it would all go down in the pit, and then they used to call the boy – he would have to go down and hump all this rubbish out, mucky, dirty, and it would have to go back to being pulped. But it was hot – most of the men down there they would just wear shorts, it was so hot there. You could go and jump in the river or get thrown in the river, and go and stand at the back of the mill, the paper making machines, you’d be dry, just like that. It was that hot the boys just used to – and people on the paper making machines never had no break. The boy would have to go and get their dinner from the canteen because they just kept running all the time.

Int: And did the machines run like 24 hours a day?

B: Non-stop. 24 hours.

Int: And then when it was the two week break, they shut the entire complex and everybody had two weeks holiday..

B: Yes. Croxley was empty.

S: Yes, the whole of Croxley was on holiday.

B: Yes, Croxley was empty then. They were massive.

Int: Was that in August – an August break?

S: The last week in July and the first week in August.

B: Every year, yes.

S: But the prices for a holiday used to go up the same as they do now.