Anonomously recorded history of Croxley Green

We are unsure where the information below came from and who indeed took the time to collect and record all the information. We do however, believe that it should be shared as it is an indication of our local history through the eyes of an unknown local resident who must have spent a lot of time researching Croxley Green before finalising it in March 1950.

Forward

“Let us not lightly cast aside anything that belongeth to the Past, for only with the Past can we rear the fabric of the Future”

It has been said that “Croxley has no history”, but in the course of the thousands of years that Man has trod the Earth, it is doubtful if an inch of any British parish has remained untrodden. Each of these footfalls has facilitated some purpose of the person, who made it, and each purpose has preceded some happening, large or small, that in itself has become part of a scheme of things that has ultimately made history. The tiny stream of events in our small parish therefore, has joined a river of Hertfordshire happenings that in its turn has helped to swell the greater river of British History. As such, Croxley has played its part in the history of an island that has exercised great influence on the destiny of the whole world.

But the story of Croxley is not one of footfalls alone. We know that very early man lived here, and that successive generations have found it a desirable place in which to remain. It has served, and still serves the purposes of great men, and adjoining parishes have been as dependent on Croxley, as Croxley has been dependent on them. It is no mere dormitory area, for we can boast local industry in fair proportion to our population, and this continued expansion of both assures us of an increasingly important place in local affairs.

Our place name has been spelt in various ways over the years, and these will appear in their chronological order as the pages of our story unfold.

It has been said that “Croxley has no history”, but in the course of the thousands of years that Man has trod the Earth, it is doubtful if an inch of any British parish has remained untrodden. Each of these footfalls has facilitated some purpose of the person, who made it, and each purpose has preceded some happening, large or small, that in itself has become part of a scheme of things that has ultimately made history. The tiny stream of events in our small parish therefore, has joined a river of Hertfordshire happenings that in its turn has helped to swell the greater river of British History. As such, Croxley has played its part in the history of an island that has exercised great influence on the destiny of the whole world.

But the story of Croxley is not one of footfalls alone. We know that very early man lived here, and that successive generations have found it a desirable place in which to remain. It has served, and still serves the purposes of great men, and adjoining parishes have been as dependent on Croxley, as Croxley has been dependent on them. It is no mere dormitory area, for we can boast local industry in fair proportion to our population, and this continued expansion of both assures us of an increasingly important place in local affairs.

Our place name has been spelt in various ways over the years, and these will appear in their chronological order as the pages of our story unfold.

March 1950 - ANON

3000 BC

Some 15,000 years ago, perhaps more, a community of people lived by a small lake or pond. For food they trapped the mammoth, the cave bear or the woolly haired rhinoceros, in pits which were torn from the ground with rough flint tools. Their cooking arrangements were most primitive, as they had not learned to fashion vessels that would endure great heat, and their dress was of the fur and skin of the animals they killed. They did not cultivate the soil, and lived by the waterside in natural shelter or in tents made of skin. One of these spots we now know as Long Valley Wood, Croxley Green, and we know that these Palaeolithic men lived here because they left behind them their rough flint “hand axes” and other smaller tools. These we have found, with a tooth and a tusk of the mammoths they hunted. We have found no remains of the men themselves because they did not bury their dead, and their primitive shelters have long since decayed, but we have found “pot boilers” - stones that were heated in their fires and dropped into flimsy vessels of food.

Some thousands of years elapsed and this type of man was driven away by the climate, which was becoming milder and damper. He was replaced by a new type of Man whom we call Neolithic, who cultivated the soil a little, and who also lived here. He learned not only to fashion implements, but to grind and polish them to a fair condition. So far we do not know that he left his tools behind in Croxley, but he has left many chippings from his tool-making, and from these we may assume that he lived and worked here. For how long his kind was here, or whether he survived through to the Bronze Age it is impossible to say, but excellent 3,000 year old evidence of Bronze Age man has been found nearby in Rickmansworth.

Some thousands of years elapsed and this type of man was driven away by the climate, which was becoming milder and damper. He was replaced by a new type of Man whom we call Neolithic, who cultivated the soil a little, and who also lived here. He learned not only to fashion implements, but to grind and polish them to a fair condition. So far we do not know that he left his tools behind in Croxley, but he has left many chippings from his tool-making, and from these we may assume that he lived and worked here. For how long his kind was here, or whether he survived through to the Bronze Age it is impossible to say, but excellent 3,000 year old evidence of Bronze Age man has been found nearby in Rickmansworth.

55 BC / 411 AD

There is but scant evidence as yet of Roman influence in Croxley, although it is believed to have stood on a Romano-British road. This probably ran north-west and south-east along the watershed between the Chess on the south and west, and the Gade and Bulbourne on the north and east, joining Ackerman Street and the Icknield Way at Tring. To the south-east it probably ran over Croxley Green and by Batchworth Heath into Ruislip. More conclusive evidence is perhaps yet to come, but we do know that after the Romans had left Britain, the Saxons established themselves in Croxley.

757 AD

During the years AD 757 – 796, Offa, a fierce and warlike man and the ruthless conqueror of the lands adjoining his own, was the Saxon King of Mercia, a kingdom embracing most of Central England at that time. It is perhaps due to this very ruthlessness that we owe our next knowledge of Croxley’s history. Offa gave his daughter in marriage to Ethelbert, King of East Anglia, assassinated the bridegroom in the midst of the wedding festivities, and added the victim’s Kingdom to his own. His daughter, aghast at her father’s callous act, died heartbroken and unforgiving, and the murderer himself was left alone and despised. His conversion to Christianity, a pilgrimage to Rome, the founding of the Monastery of St. Albans, and its endowment with many manors – all were acts of atonement to little avail, for he himself died of remorse two years after the murder. Among these many endowments to St. Albans was one of the four manors of Rickmansworth, which later became known as Croxley, and this association was to last for almost 800 years. The Saxons were tillers of the soil; they made their own clothes, and lived as far as possible independently of the outside world. Their manorial system involved the serfdom of many of the tenants, who had to cultivate their land, but were not free to leave it. Even permission to marry had to be obtained from the Lord of the Manor, who drew goods by way of rent, and who could command both peaceful and military service from his serfs.

The word “moor”, which survives today in Croxley Moor and Moor Park, was used much more extensively in the past, as old maps of Croxley show, and is Anglo Saxon in origin.

The word “moor”, which survives today in Croxley Moor and Moor Park, was used much more extensively in the past, as old maps of Croxley show, and is Anglo Saxon in origin.

1016

CROC’S LEAH - The written story of Croxley probably begins when Croc, a moneyer to King Canute, reported the existence of property here round about 1016.

Though this is assumption, it cannot be dismissed as entirely fanciful, for Croc is mentioned in the capacity of moneyer in 1084 Doomsday Book, and as such he probably assessed the value of a clearing here and named it Croc’s Lea (or Leah) for taxation purposes. It is equally reasonable to assume that the prefix Croc in such place names as Croxall, Croxby, Croxdale, Croxden, Croxteth and Croxten also have the same derivation. The area covered by Croxley as we know it today would in Croc’s time have been heavily wooded country intersected by occasional tracks and with little more than the sites of the present green and Croxley Hall Farm as cultivated clearings. The woods would abound in wild game, providing both food and clothing, but water on the Green site would have been a precious commodity. The present day survival of three ponds and depressions suggestive of dew ponds, on and around the Green, are a pointer not only to antiquity, but to the need of early settlers to conserve all available moisture.

Rickmansworth at this time was considered sufficient to support 15 families and their dependants, so that the “manor” of Croxley would have been proportionally smaller.

Though this is assumption, it cannot be dismissed as entirely fanciful, for Croc is mentioned in the capacity of moneyer in 1084 Doomsday Book, and as such he probably assessed the value of a clearing here and named it Croc’s Lea (or Leah) for taxation purposes. It is equally reasonable to assume that the prefix Croc in such place names as Croxall, Croxby, Croxdale, Croxden, Croxteth and Croxten also have the same derivation. The area covered by Croxley as we know it today would in Croc’s time have been heavily wooded country intersected by occasional tracks and with little more than the sites of the present green and Croxley Hall Farm as cultivated clearings. The woods would abound in wild game, providing both food and clothing, but water on the Green site would have been a precious commodity. The present day survival of three ponds and depressions suggestive of dew ponds, on and around the Green, are a pointer not only to antiquity, but to the need of early settlers to conserve all available moisture.

Rickmansworth at this time was considered sufficient to support 15 families and their dependants, so that the “manor” of Croxley would have been proportionally smaller.

1166

CROKESLEYA - The first inhabitant to have his name recorded for posterity was one Richard de Croxley who was a Knight of St. Albans in 1166. It is known that he gave a mill at Croxley to the Nunnery of St. Mary, Clerkenwell, this being no mean endowment for Richard as Lord of the Manor had the right to compel all tenants to have their corn ground at his mill. It is further recorded that he paid taxes on his land in Hertfordshire in 1176. In 1182 the Manorial rights of Oxhey and Croxley combined to make a total of one “knight’s fee” to St. Albans and a large share of the Manorial rights seemed to have been retained by successive branches of the de Croxley family until the early 1300’s. (Cussans quotes the family name as Creke or Croke). The last of the de Croxley line were two brothers, Richard and Roger (or Robert). Richard died without heirs, but Roger left three daughters – Petronel de Amenesville, Beatrice wife of John de Shelford and Joan de Wauncy. The heirs of these three ladies finally conveyed the manor to the Abbot of St. Albans. It must be remembered that there was more than one manor house in Croxley from quite early times, and it is possible for one to become confused with different Lords of the same Manor.

1291

Be that as it may it certainly appears that St. Albans had much interest in Croxley, with possessions here 1310 until the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Thus we learn from Clutterbuck that Croxley Manor “was appropriated to the Cellarers of St. Albans” 1320 with the following Cellarers as Lords of the Manor - 1291-95 Luke Bovingdon, 1310-13) Thomas de Bovingedean, 1320-23 William Heron. We learn also that in 1194 the Hospital of St. Mary de Pré at St. Albans was granted by the Monastery “two acres beyond the spinney called Le Copdethorne” and Newcome, historian of St. Albans Abbey also mentions Copthorne Wood.

Two Croxley farms are recorded in 1200’s - that belonging to Ralph Pyrot in 1248 (Parrotts) and Simon Duraunt in 1278 (Durrants).These two individuals would hardly have dared imagine that 700 years later their names would have become household words, with estates, schools and streets named after them. The name Pyrot by 1665 changed to Parrett, when one Elizabeth Parrett was recorded in the Parish Registers. A further reference to the De Croxley family comes to light about 1255 when a small chantry in Watford Parish Church was founded by Petronel de Ameneville the previously mentioned widowed daughter of Robert de Croxley. She occupied the Manor of Cassiobury, and regularly provided 600 eggs and 24 cheeses to St Albans Abbey whose brethren (in the absence of a resident Vicar) administered to the spiritual needs of Watford and district of those far off days.

Also in the middle pf the 13th Century, we learn that an Abbot Richard de Crokesley (presumably an Abbot of Westminster) had erected a chapel near the north door of Westminster Abbey, and dedicated it to St. Edmund. The chapel was later pulled down by Henry III prior to the rebuilding of the church.

1198 - 1301 CHOCHESLE

Two Croxley farms are recorded in 1200’s - that belonging to Ralph Pyrot in 1248 (Parrotts) and Simon Duraunt in 1278 (Durrants).These two individuals would hardly have dared imagine that 700 years later their names would have become household words, with estates, schools and streets named after them. The name Pyrot by 1665 changed to Parrett, when one Elizabeth Parrett was recorded in the Parish Registers. A further reference to the De Croxley family comes to light about 1255 when a small chantry in Watford Parish Church was founded by Petronel de Ameneville the previously mentioned widowed daughter of Robert de Croxley. She occupied the Manor of Cassiobury, and regularly provided 600 eggs and 24 cheeses to St Albans Abbey whose brethren (in the absence of a resident Vicar) administered to the spiritual needs of Watford and district of those far off days.

Also in the middle pf the 13th Century, we learn that an Abbot Richard de Crokesley (presumably an Abbot of Westminster) had erected a chapel near the north door of Westminster Abbey, and dedicated it to St. Edmund. The chapel was later pulled down by Henry III prior to the rebuilding of the church.

1198 - 1301 CHOCHESLE

1326

In 1326 Abbot Richard de Wallingford stayed at the Manor House of Croxley on his return from Rome, where he had been to obtain confirmation of his Abbacy from the Pope.

Abbot Richard has been described as being renowned for his piety and learning, a man who for the time in which he lived possessed a wonderful scientific knowledge, and who could command immense wealth and influence. Our interest in this Abbot lies not only in his great learning, but in the fact that he is a reminder of one of the scourges through which Croxley has passed. He was a leper, and only his prestige enabled him, though not without great trouble and scheming, to maintain his place at the Abbey until his death in 1335.

St. Julian’s Hospital, a lazar house at St. Albans, founded by Abbot Geoffrey de Gorham early in the 12th Century, was endowed by local tithes “for the good of the souls” of (among others) King Offa of Mercia and Abbot Richard the leper.

1349 – 96 CROKESLEIGRENE

An interesting pen picture of Croxley at this time is provided in “Red Dicken” by Tom Bevan (late headmaster of Rickmansworth C. of E. School),

The French wars of Edward III, says Bevan, though victorious for England, had emptied the royal exchequer, taxation was heavy and the country was poor. On the return of the men who had been common soldiers, many found that they could no longer be maintained by the manors and took to the woods as footpads or robbers. The in 1349 came the “Black Death”, a plague that carried off half the population of the kingdom and the supply of labour fell far short of the demand. Those peasants who had bought their freedom found themselves being pressed back into serfdom by legislation that savoured of trickery. Resulting from the intrigue and oppression of this period Bevan tells how Red Dickon the Elder is arrested by Roger of Bachenworth for the murder of John de Brent, farmer of the demesne of the Manor of Rickmersworth, and found guilty by the Abbot of St. Albans. His son, Red Dickon the younger, is sentenced to outlawry, and is present at his father’s execution. The boy spends a Robin Hood existence, for, as the book says “with the exception of a few small tracts of cultivated ground, dense woodland extended right away to Rickmersworth and many miles beyond. Here then were hundreds of square miles of almost unbroken forest, and within its shadows roamed countless wild creatures and many bands of desperate men”. One such band is described as being “encamped in a dell that lay about a mile from the hamlet of Cassio”, beyond which “the wooded hill rose abruptly towards the thatched roofs of Crokesley”. They hear how Roger of Bachenworth “was that forenoon speaking with Oswald, the reeve of Crokeslay; after which he rode down the hill and along the bridle path to Watford”.

The story goes on to tell how Red Dickon and his comrades play their part in Wat Tyler’s peasants’ revolt. “The men of Rickmersworrth swung into line and marched off towards St. Albans, picking up the men of Crokesley and Cassio on their way”. The immediate outcome of the revolt was, of course, untimely, but finally with the aid of his comrades, Red Dickon vindicated his father’s honour, and Oswald of Crokesley is found to be the villain of the piece. Dickon becomes a free man once more, marries his chieftain’s daughter and returns to his home “on the brow of the low hill that shut in Rickmersworth from the South”.

Abbot Richard has been described as being renowned for his piety and learning, a man who for the time in which he lived possessed a wonderful scientific knowledge, and who could command immense wealth and influence. Our interest in this Abbot lies not only in his great learning, but in the fact that he is a reminder of one of the scourges through which Croxley has passed. He was a leper, and only his prestige enabled him, though not without great trouble and scheming, to maintain his place at the Abbey until his death in 1335.

St. Julian’s Hospital, a lazar house at St. Albans, founded by Abbot Geoffrey de Gorham early in the 12th Century, was endowed by local tithes “for the good of the souls” of (among others) King Offa of Mercia and Abbot Richard the leper.

1349 – 96 CROKESLEIGRENE

An interesting pen picture of Croxley at this time is provided in “Red Dicken” by Tom Bevan (late headmaster of Rickmansworth C. of E. School),

The French wars of Edward III, says Bevan, though victorious for England, had emptied the royal exchequer, taxation was heavy and the country was poor. On the return of the men who had been common soldiers, many found that they could no longer be maintained by the manors and took to the woods as footpads or robbers. The in 1349 came the “Black Death”, a plague that carried off half the population of the kingdom and the supply of labour fell far short of the demand. Those peasants who had bought their freedom found themselves being pressed back into serfdom by legislation that savoured of trickery. Resulting from the intrigue and oppression of this period Bevan tells how Red Dickon the Elder is arrested by Roger of Bachenworth for the murder of John de Brent, farmer of the demesne of the Manor of Rickmersworth, and found guilty by the Abbot of St. Albans. His son, Red Dickon the younger, is sentenced to outlawry, and is present at his father’s execution. The boy spends a Robin Hood existence, for, as the book says “with the exception of a few small tracts of cultivated ground, dense woodland extended right away to Rickmersworth and many miles beyond. Here then were hundreds of square miles of almost unbroken forest, and within its shadows roamed countless wild creatures and many bands of desperate men”. One such band is described as being “encamped in a dell that lay about a mile from the hamlet of Cassio”, beyond which “the wooded hill rose abruptly towards the thatched roofs of Crokesley”. They hear how Roger of Bachenworth “was that forenoon speaking with Oswald, the reeve of Crokeslay; after which he rode down the hill and along the bridle path to Watford”.

The story goes on to tell how Red Dickon and his comrades play their part in Wat Tyler’s peasants’ revolt. “The men of Rickmersworrth swung into line and marched off towards St. Albans, picking up the men of Crokesley and Cassio on their way”. The immediate outcome of the revolt was, of course, untimely, but finally with the aid of his comrades, Red Dickon vindicated his father’s honour, and Oswald of Crokesley is found to be the villain of the piece. Dickon becomes a free man once more, marries his chieftain’s daughter and returns to his home “on the brow of the low hill that shut in Rickmersworth from the South”.

1364

All that official documents can tell us about Croxley in this restless time is that it was a hamlet, and that in 1364 rents from a tenement called Elyslond were drawn by John, son of William Aignell. One of the oldest buildings in Croxley is undoubtedly the Tithe Barn of Croxley Hall Farm which is the present Manor house. The barn is over 500 years old, although the farm itself was the home farm of the Manor of the Moor which is first mentioned in 1182. The barn, claimed to be the second largest in England, measures 101 feet by 38 feet 6 inch wide. The height inside from floor to ridge is about 35 feet. In the centre of the east side is a lofty transept with doors large enough to admit a fully loaded hay cart, which would pass over the 400 year old flailing floor of 4” thick oak boards. Also on the east side the tiled roof sweeps down to walls five feet high, continuing to form low external sheds. The walls are built of flint with quoine and coping of Totternhoe stone, though brickwork patching of various ages is evident. The internal timbering is most impressive, cathedral like in effect, and is of either old chestnut or oak. Both woods were used in mediaeval times (old ship’s timbers being in great demand) and it is difficult to distinguish one from the other.

1433 / 1457

The Court Rolls and Rentals of the Manor Cassiobury in 1433 brings to light again the name of Copthornfield. It is difficult to imagine another name so intriguingly romantic as “The Manor of the Moor”, and equally difficult to find another mansion with as many historic associations. The influence of the Manor on the development of its environs must have been very great, and Croxley and Rickmansworth night have been far less significant today without it.

“The Manor of the Moor” was bestowed on the Monastery of St. Albans by King Offa, at the same time as Croxley, and the tenants held it by “Knights fee” to the Abbot. Mention is made of the settlement of a dispute in 1090 between the Earl of Northumberland and the Bishop of Durham in which the management and revenues of the monastery at Tynemouth (near Newcastle) were transferred to Durham, a condition of the settlement being the insertion of a covenant in the deed of the Manor of the Moor that the tenant should provide a “palfrey on which the abbot should ride whenever he wished to visit that cell”. It was further stipulated that “the horse should be sound and strong, that it might be capable of so long a journey”. (Bayne’s “Moor Park” and Brand’s “History of Newcastle”.) Successive tenants held the Manor by Knights Fee to the Abbot of St. Albans, until we learn that in 1457 Ralph de Boteler, having disputed that he held it from the Abbot, finally compromised by paying the Abbey a penny a year. He was a descendant of the cup-bearers to the Norman dukes, from which it is assumed that the name Boteler was taken – forerunner of the present word “butler”.

“The Manor of the Moor” was bestowed on the Monastery of St. Albans by King Offa, at the same time as Croxley, and the tenants held it by “Knights fee” to the Abbot. Mention is made of the settlement of a dispute in 1090 between the Earl of Northumberland and the Bishop of Durham in which the management and revenues of the monastery at Tynemouth (near Newcastle) were transferred to Durham, a condition of the settlement being the insertion of a covenant in the deed of the Manor of the Moor that the tenant should provide a “palfrey on which the abbot should ride whenever he wished to visit that cell”. It was further stipulated that “the horse should be sound and strong, that it might be capable of so long a journey”. (Bayne’s “Moor Park” and Brand’s “History of Newcastle”.) Successive tenants held the Manor by Knights Fee to the Abbot of St. Albans, until we learn that in 1457 Ralph de Boteler, having disputed that he held it from the Abbot, finally compromised by paying the Abbey a penny a year. He was a descendant of the cup-bearers to the Norman dukes, from which it is assumed that the name Boteler was taken – forerunner of the present word “butler”.

1460

In 1460 George Nevil, Bishop of Exeter and Lord Chancellor, brother of Warwick the King Maker obtained a licence from Henry VI to enclose 600 acres in the parishes of Rickmansworth and Watford, and on the north-eastern portion be built a country residence of great magnificence. This represents one certain move of the site of the manor, and it is quite possible that the manor house was located in more than these two positions over the course of centuries until it’s finally becoming Moor Park.

Nevil lived here in grand style and Edward IV was frequently entertained at the “More”.

An extract from an unpublished “History of Rickmansworth” by Mr. A. Montgomerie an occupier of Moor Park of the present century says that:

“About 1416 the Manor of the More was conveyed to a William Fleet who, a few years later, put up a claim to have a right of way for himself and his cattle from the More, across the fields to the market place and church of Watford, in other words, along Tolpits Lane. The Abbot of St. Albans went to law and William Fleet failed to gain his point.

The More did not get its road to Watford till a century later when a greater Cardinal, even than Beaufort, - Cardinal Wolsey, extended the Park by seizing the lands of Tolpits and constructing the road.”

The Harleian MSS, contain an “Inventorie of ye Ganderobe of King Henry VIII as ye Manor of ye More in the County of Herts” which suggests that the manor had become a royal residence, and as such came into the possession of Cardinal Wolsey.

Opulent, and at the height of his power, Wolsey “enlarged or rebuilt” (Bayne) Nevil’s mansion, and here it was that the King signed the “Treaty of the More” with Francis I. It was here also in 1529 that Wolsey entertained for a month in regal style, Henry VIII and his Queen Catherine of Arragon, with Anne Boleyn in attendance.

“His banquets” says Cavendish in his “Life of Wolsey”, “were set forth with masques and mummeries in so gorgeous a sort, and in so costly a manner, that it was a heaven to behold”. Tradition says that the Tythe Barn was Wolsey’s slaughter house, and the imagination can supply an inventory of the foodstuffs supplied by Croxley farms.

Wolsey’s power was to wane, however, and it was from Moor Park that he journeyed to London to be found guilty of having illegally received bulls from the Pope. As a result he was stripped of all his property and “The Manor of the More” went into the hands of the Crown.

The name Tolpits had existed well before Wolsey’s time – as “Tolpade” in 1364, evolving to “Twopits” in 1822 and “Tolput” in 1803. The name (says the “Watford Rural District Guide”) “seems to come from ‘toll path’ and was an alternative name for the Cassio mill mentioned in 1086”.

Nevil lived here in grand style and Edward IV was frequently entertained at the “More”.

An extract from an unpublished “History of Rickmansworth” by Mr. A. Montgomerie an occupier of Moor Park of the present century says that:

“About 1416 the Manor of the More was conveyed to a William Fleet who, a few years later, put up a claim to have a right of way for himself and his cattle from the More, across the fields to the market place and church of Watford, in other words, along Tolpits Lane. The Abbot of St. Albans went to law and William Fleet failed to gain his point.

The More did not get its road to Watford till a century later when a greater Cardinal, even than Beaufort, - Cardinal Wolsey, extended the Park by seizing the lands of Tolpits and constructing the road.”

The Harleian MSS, contain an “Inventorie of ye Ganderobe of King Henry VIII as ye Manor of ye More in the County of Herts” which suggests that the manor had become a royal residence, and as such came into the possession of Cardinal Wolsey.

Opulent, and at the height of his power, Wolsey “enlarged or rebuilt” (Bayne) Nevil’s mansion, and here it was that the King signed the “Treaty of the More” with Francis I. It was here also in 1529 that Wolsey entertained for a month in regal style, Henry VIII and his Queen Catherine of Arragon, with Anne Boleyn in attendance.

“His banquets” says Cavendish in his “Life of Wolsey”, “were set forth with masques and mummeries in so gorgeous a sort, and in so costly a manner, that it was a heaven to behold”. Tradition says that the Tythe Barn was Wolsey’s slaughter house, and the imagination can supply an inventory of the foodstuffs supplied by Croxley farms.

Wolsey’s power was to wane, however, and it was from Moor Park that he journeyed to London to be found guilty of having illegally received bulls from the Pope. As a result he was stripped of all his property and “The Manor of the More” went into the hands of the Crown.

The name Tolpits had existed well before Wolsey’s time – as “Tolpade” in 1364, evolving to “Twopits” in 1822 and “Tolput” in 1803. The name (says the “Watford Rural District Guide”) “seems to come from ‘toll path’ and was an alternative name for the Cassio mill mentioned in 1086”.

1533

Croxley’s last memorial tie with St. Albans was Thomas Whethamstede, a cellarere of the monastery who was Lord of the Manor from 1533 – 6.

Tom Bevan has described these cellarers as “sleek with good living, and rubicund by virtue of long and intimate acquaintance with the juice of the grape”.

Tom Bevan has described these cellarers as “sleek with good living, and rubicund by virtue of long and intimate acquaintance with the juice of the grape”.

1538

From 1538 the Manor was held under lease for 44 years by William Baldwin, a name prominent in the district for many years, and perpetuated in the existing Baldwins Lane. The name of the lane is said to be derived from one Margaret Baldwin, whose name appeared in the parish registers of 1581.

In Fitzherbert’s “Book of Surveying and Improvement”, published in 1539, he describes the system of communal agriculture then in use. “To every townshyppe that standeth in tillage in the playne country, there be errable lands to plowe, and sowe, and leyse to tye or tedder theyr horses and mares upon, and common pasture to kepe and pasture their catell beestes, and shepe upon, and also they have meadowe grounds to get theyr hay upon.” Thus we find in Croxley ancient reference to “The Common Moor for the Tennants of Croxley Manour”, the Horse Moor, and Lott Mead (of which more anon). Stories persist of the maintenance of common rights in Croxley, and it is notable that in 1886 when Dickinson’s Mill was greatly expanded, land was purchased by the firm from Lord Ebury to be exchanged for Common Moor land adjoining the Mill.

It is said that in the building of Tolpits Lane for Wolsey it was necessary to demolish a farmhouse or cottage on the Moor. This was rebuilt nearby, and another story of the common rights is associated with it. This Tolpits Cottage caught fire and the villagers turned out en masse to extinguish it. As a mark of gratitude the tenant is said to have granted the use of the Moor to the villagers for all time as common grazing land for cattle and horses. Unfortunately the date of this event is lost in the mists of antiquity and it cannot be said whether it was before or after Wolsey’s time.

The dictionary definition of “Moor” is “poor, peaty, untilled ground, often covered with heath”, so the “tenants of the manour” are in any case probably grimly standing their last ground!

In 1545 mention is found of the name William Jackett of Oxhey. The Jacketts were prominent in this party of Hertfordshire up to the 17th century, and it is said that traces of Jacotts Toft (or farmhouse) and the marks of ridge and furrow may still be seen near Jacotts Hill in Cassiobury Park. Thus it is that we find old references to Jaggerts Pightie in our parish, the pightie being a variation of pinkle or pightle – a small enclosure near a house, a small piece of land “picked off” from an open field.

In Fitzherbert’s “Book of Surveying and Improvement”, published in 1539, he describes the system of communal agriculture then in use. “To every townshyppe that standeth in tillage in the playne country, there be errable lands to plowe, and sowe, and leyse to tye or tedder theyr horses and mares upon, and common pasture to kepe and pasture their catell beestes, and shepe upon, and also they have meadowe grounds to get theyr hay upon.” Thus we find in Croxley ancient reference to “The Common Moor for the Tennants of Croxley Manour”, the Horse Moor, and Lott Mead (of which more anon). Stories persist of the maintenance of common rights in Croxley, and it is notable that in 1886 when Dickinson’s Mill was greatly expanded, land was purchased by the firm from Lord Ebury to be exchanged for Common Moor land adjoining the Mill.

It is said that in the building of Tolpits Lane for Wolsey it was necessary to demolish a farmhouse or cottage on the Moor. This was rebuilt nearby, and another story of the common rights is associated with it. This Tolpits Cottage caught fire and the villagers turned out en masse to extinguish it. As a mark of gratitude the tenant is said to have granted the use of the Moor to the villagers for all time as common grazing land for cattle and horses. Unfortunately the date of this event is lost in the mists of antiquity and it cannot be said whether it was before or after Wolsey’s time.

The dictionary definition of “Moor” is “poor, peaty, untilled ground, often covered with heath”, so the “tenants of the manour” are in any case probably grimly standing their last ground!

In 1545 mention is found of the name William Jackett of Oxhey. The Jacketts were prominent in this party of Hertfordshire up to the 17th century, and it is said that traces of Jacotts Toft (or farmhouse) and the marks of ridge and furrow may still be seen near Jacotts Hill in Cassiobury Park. Thus it is that we find old references to Jaggerts Pightie in our parish, the pightie being a variation of pinkle or pightle – a small enclosure near a house, a small piece of land “picked off” from an open field.

1541

CROSLEY - Previous mention of there having been more than one manor of Croxley is borne out by records of 1541 quoting “a messuage or manor called Crosley”, which, says the Victoria History of England (Part 23a) is now called Parrot’s Farm. This manor, probably secondary in importance, was conveyed by John Wingbourn to Ralph Morris, who in 1562 together with Henry Wingbourn and Elizabeth his wife sold it to Henry Mayne. Henry’s son and heir held it at this time “of the master and college of Gonville and Caius as of their manor of Croxley”. Successive heirs remained in occupation until 1656 when the lease was sold to Daniel Parrett, whose descendants held the property for 142 years. CROXLEY HALL MEADE

1556

Reverting to the Manor House now called Croxley Hall Farm, we find that on the expiration of William Baldwin’s lease, the manorial rights and emoluments of Croxley Green and neighbourhood were conferred by Queen Elizabeth upon Dr. John Caius. His real name was Kaye, which he Latinized to Caius, a native of Norwich, a learned man and voluminous author who was called the Prince of Physicians. He had served Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth in turn as physician to the Royal Household. The present Caius College Cambridge was originally a hall, and from the name of its founder was called Gonville Hall and here Dr. Caius had been educated. He greatly enlarged and endowed it, obtaining permission from Queen Mary to be a co-founder and to changes its name to Gonville and Caius College. His endowments to the College include the Manor of Croxley and estates in Cambridgeshire, Dorset and Norfolk, which have remained vested in that foundation ever since. Two scholarships in the college are restricted to natives of Hertfordshire. Dr. Caius died in 1573, his remains being conveyed to Cambridge and buried in his chapel there.

The existing manor house would have been built at about this time, though the exterior has been extensively refaced and modernized. The building is of two stories with what seems to have been a central hall extending from front to back of the house. On the west side of the hall is a panelled parlour with woodwork unspoiled over the centuries, and on the east side the front entrance and kitchens. The room adjoining the parlour has a modern fireplace, but the remains of an ingle-nook are visible. The house has the reputation of being extremely cold, in spite of the impression given by its most striking feature – a massive red brick chimney at the west end of the building. The bricks are obviously mediaeval being 2¼” in average thickness. The chimney contains the unusual feature of a window in an arched recess at its base. Whether or not this chimney was originally a “central heating” device of an earlier building extending further westward is a matter of conjecture. The manor house is at present occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Sanson.

The present Doggett’s Cottage is said to be Tudor, and as such may be contemporary with the manor house; the bricks of the chimney are 2¼” in thickness, a common mediaeval size.

The existing manor house would have been built at about this time, though the exterior has been extensively refaced and modernized. The building is of two stories with what seems to have been a central hall extending from front to back of the house. On the west side of the hall is a panelled parlour with woodwork unspoiled over the centuries, and on the east side the front entrance and kitchens. The room adjoining the parlour has a modern fireplace, but the remains of an ingle-nook are visible. The house has the reputation of being extremely cold, in spite of the impression given by its most striking feature – a massive red brick chimney at the west end of the building. The bricks are obviously mediaeval being 2¼” in average thickness. The chimney contains the unusual feature of a window in an arched recess at its base. Whether or not this chimney was originally a “central heating” device of an earlier building extending further westward is a matter of conjecture. The manor house is at present occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Sanson.

The present Doggett’s Cottage is said to be Tudor, and as such may be contemporary with the manor house; the bricks of the chimney are 2¼” in thickness, a common mediaeval size.

1620

The imposing building we now know as Croxley House is built on the site of two tenements in existence before 1620 known as “Harry Smith’s” and “Harwood’s” or Harwell’s”, and owned at that time by one William Sansome. As “Harry Smith’s” he conveyed the property in1620 “to the use of Mary, wife of Richard Tompson of Watford”. In Harry’s will, the property was left to her grandchild Mary wife of John Beckett in 1653.

1653

In this year Cromwell’s short period of administration began and more than one building in Croxley lays claim to having housed his troops. Notable among these is the Tithe Barn, and it is not improbable that such was the case. What are said to be Cromwellian relics were found by workmen during renovations at “The Parrotts” and have since been handed to the County Museum Authorities. It had been fashionable in these times for wealthy London families to emigrate to the country areas to escape the yearly visitation of the plague. During the Civil War, however, Hertfordshire offered but poor refuge to such people, for the years of 1648/9 were terrible famine years. There had been almost continuous rain in Hertfordshire throughout 1648, and frequent outbreaks of plague occurred in the country during the years of the war.

Among the families who settled in the neighbourhood in the 18th century were several branches of the previously mentioned Baldwins or Baldyns, and certainly one Henry Baldwin was baptised in Watford Church as early as 1525.

There is record also of Anne Baldwin, who in 1656 was granted a license to keep a “Taverne” and to sell wine by retail at the sign of the Swan in Rickmansworth. Not the least of the Bald wins’ interests in the Croxley area was the possession and probably the building of the mansion “Red Heath”, the copyhold part of the estate being held “of the Manor of Croxley Hall and Cassio”. It was originally called “Reedheath” and here died “Henry Baldwyn (sone of Henry Baldwyn) a young man of espetial meeknesse and Playnesse of Hart, who gave his soule to God in the floure of his youth A.D.1601”.

Williams, the Watford historian of 1885 says “There is in the servant’s hall of the mansion a fine old carved oak table that is described in an inventory of the goods in the house, dated 1639, “one longe table with the frame”. It is in an excellent state of preservation, and a clock also there appears to be of similar age and state”.

It was in 1672 that William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania married Gulielma Springett of Chalfont St. Giles, settling in Rickmansworth at what is now Basing House, the Council Offices. Possessed of ample means, Penn apparently adopted the life of a country gentleman “and for three years his busy spirit contented itself with preaching up and down the neighbouring villages, and with the writing of countless Quaker pamphlets, both offensive and defensive” – (William Penn Mabel C. Brailsford). The, in 1675, Richard Baxter (the eminent preacher and controvertionalist of that period) visited the district and entered into open controversy with the local Quakers. In Ormer “Life and Times of Baxter” we read:

“The country about Rickmansworth abounding with Quakers, because William Penn, their captain, dwelleth there, I was desirous that the poor people should for once hear what is to be said for their recovery, which coming to Mr. Penn’s ears, he was forward to a meeting where we continued speaking to two rooms-full of people, fasting, from ten o’clock till five; one lord, two knights and four conformable ministers, besides others being present, some all the time, some part.”

Yet, strangely enough, despite Penn’s great local influence, there is today an absence of Quakerism in the immediate vicinity of Croxley Green. There is no Friends Meeting House either in Rickmansworth or Croxley. This present day absence of Quaker adherents is doubtless due to an exodus of Penn’s local followers with him to Pennsylvania in the 1680’s. Says the Rev. R. Bayne (in his Historical Sketch of Rickmansworth and the surrounding Parishes) – “The Friends who remained in the neighbourhood after the departure of their brethren continued to assemble regularly for worship at Chorley Wood”. There was a burying ground connected with this meeting house, the last internment being made in 1836.

Although there is no actual evidence, it may well be that Croxley’s loss has been Pennsylvania’s gain, and it is interesting to speculate on the possible influence that Croxley-bred emigrants may have exercised on American affairs.

An interesting glimpse of the district in Penn’s time is contained in the famous diary of John Evelyn. The entry for April 18th 1680 reads: “on the earnest invitation of the Earl of Essex I went with him to his house at Cashiobere in Hartfordshire”. The estate is described in detail, and he also comments – “The land about it is exceedingly addicted to wood, but the coldnesse of the place hinders the growth. Black cherry trees prosper even to considerable timber, some being 80 foote long”.

Thus we know that certain of Croxley’s natural characteristics have persisted down the years, not forgetting his further observations – “but the soil is stonie, churlish, and uneven,” which, of course, might be interpreted as a measure of sympathy to present day gardeners.

Among the families who settled in the neighbourhood in the 18th century were several branches of the previously mentioned Baldwins or Baldyns, and certainly one Henry Baldwin was baptised in Watford Church as early as 1525.

There is record also of Anne Baldwin, who in 1656 was granted a license to keep a “Taverne” and to sell wine by retail at the sign of the Swan in Rickmansworth. Not the least of the Bald wins’ interests in the Croxley area was the possession and probably the building of the mansion “Red Heath”, the copyhold part of the estate being held “of the Manor of Croxley Hall and Cassio”. It was originally called “Reedheath” and here died “Henry Baldwyn (sone of Henry Baldwyn) a young man of espetial meeknesse and Playnesse of Hart, who gave his soule to God in the floure of his youth A.D.1601”.

Williams, the Watford historian of 1885 says “There is in the servant’s hall of the mansion a fine old carved oak table that is described in an inventory of the goods in the house, dated 1639, “one longe table with the frame”. It is in an excellent state of preservation, and a clock also there appears to be of similar age and state”.

It was in 1672 that William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania married Gulielma Springett of Chalfont St. Giles, settling in Rickmansworth at what is now Basing House, the Council Offices. Possessed of ample means, Penn apparently adopted the life of a country gentleman “and for three years his busy spirit contented itself with preaching up and down the neighbouring villages, and with the writing of countless Quaker pamphlets, both offensive and defensive” – (William Penn Mabel C. Brailsford). The, in 1675, Richard Baxter (the eminent preacher and controvertionalist of that period) visited the district and entered into open controversy with the local Quakers. In Ormer “Life and Times of Baxter” we read:

“The country about Rickmansworth abounding with Quakers, because William Penn, their captain, dwelleth there, I was desirous that the poor people should for once hear what is to be said for their recovery, which coming to Mr. Penn’s ears, he was forward to a meeting where we continued speaking to two rooms-full of people, fasting, from ten o’clock till five; one lord, two knights and four conformable ministers, besides others being present, some all the time, some part.”

Yet, strangely enough, despite Penn’s great local influence, there is today an absence of Quakerism in the immediate vicinity of Croxley Green. There is no Friends Meeting House either in Rickmansworth or Croxley. This present day absence of Quaker adherents is doubtless due to an exodus of Penn’s local followers with him to Pennsylvania in the 1680’s. Says the Rev. R. Bayne (in his Historical Sketch of Rickmansworth and the surrounding Parishes) – “The Friends who remained in the neighbourhood after the departure of their brethren continued to assemble regularly for worship at Chorley Wood”. There was a burying ground connected with this meeting house, the last internment being made in 1836.

Although there is no actual evidence, it may well be that Croxley’s loss has been Pennsylvania’s gain, and it is interesting to speculate on the possible influence that Croxley-bred emigrants may have exercised on American affairs.

An interesting glimpse of the district in Penn’s time is contained in the famous diary of John Evelyn. The entry for April 18th 1680 reads: “on the earnest invitation of the Earl of Essex I went with him to his house at Cashiobere in Hartfordshire”. The estate is described in detail, and he also comments – “The land about it is exceedingly addicted to wood, but the coldnesse of the place hinders the growth. Black cherry trees prosper even to considerable timber, some being 80 foote long”.

Thus we know that certain of Croxley’s natural characteristics have persisted down the years, not forgetting his further observations – “but the soil is stonie, churlish, and uneven,” which, of course, might be interpreted as a measure of sympathy to present day gardeners.

1700

The vicious punishments demanded by the law in bygone days are often the subject of grim reminiscence and yet in some cases the law required an almost poetic retribution. With all deference to its motive, how ironical must the retribution of the following case (published in the recent Rickmansworth Official Guide) have seemed to the dependents of the victim: “In the early eighteenth century, James Leach, a farmer of Croxley Green, was killed by falling off his cart. The jury found the death to be accidental and declared, as the law then required, that both horse and cart must be forfeited as “deodands” to be applied to pious or charitable use, because they were chattels which had been the immediate occasion of the death of the rational creature”. Not only did his dependents lose James Leach – they lost his horse and cart as well! The Church End Almshouses at Micklefield Green were founded by John Baldwin in 1700, and the last of the family to possess Red Heath was Thomas who died in 1710, leaving the property to his nephew Charles Finch.

1712

Charles added a new front to the Tudor house in 1712 which eventually became the oldest remaining part of the house. Cussans described it as “a large, old fashioned, and comfortable looking brick mansion, surmounted in the centre by a clock tower”. The clock bore the inscription George Clarke Whitechapple 1753. The Finch family were also prominent in local affairs. Elizabeth Finch who married John Waite of Bushey in 1655 was the grandmother of Susannah Wesley, the mother of the famous Wesley founders of the Methodists. One Charles Finch in 1663 had “fittingly and decently erected and constructed to no prejudice at all to the parishioners” a family pew in Watford Parish Church “for the purpose of sitting, bending the knees, and hearing Divine things”.

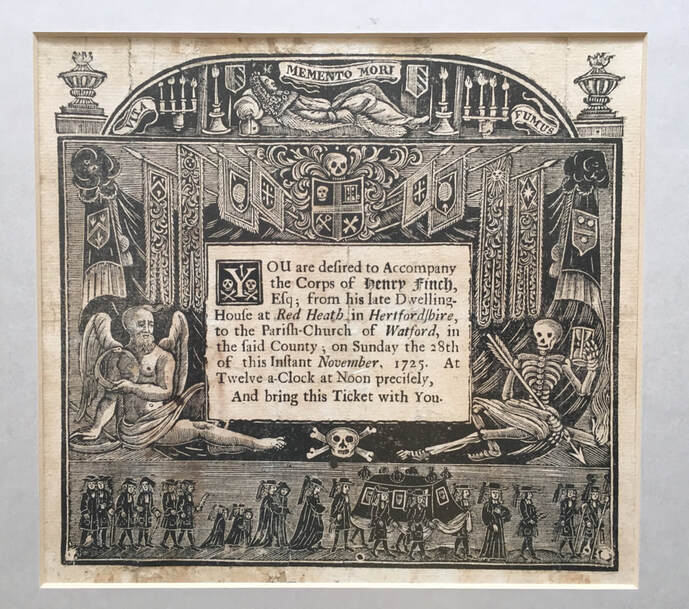

William reports having seen a funeral invitation illustrated with the recumbent figure of a man, lighted candles, death’s hand and crossed bones and a picture of the intended funeral down to the last detail, with the following inscription:-

You are desired to accompany the Corps of

Henry Finch Esq from his late dwelling house

Red Heath in Hertfordshire to the Parish Church

of Watford in the said County on Sunday the 28th

of this instant November 1725. At twelve o’clock

at noon precisely.

And bring this ticket with you.

William reports having seen a funeral invitation illustrated with the recumbent figure of a man, lighted candles, death’s hand and crossed bones and a picture of the intended funeral down to the last detail, with the following inscription:-

You are desired to accompany the Corps of

Henry Finch Esq from his late dwelling house

Red Heath in Hertfordshire to the Parish Church

of Watford in the said County on Sunday the 28th

of this instant November 1725. At twelve o’clock

at noon precisely.

And bring this ticket with you.

1750

CROSLEY GREEN - The present day survival of the mansion Lott Mead is an interesting reflection of life in the 18th century. Old maps show this meadow as being the “property of the lotters”. This meadow was divided into strips, which were marked out by wooden posts or rows of stones. Lots were then cast to give all the shareholders an equal chance for the best places of “meadowe groundes to get their hay upon”. The field-name “Starve Acre” of the same period is probably a caustic comment on the nature of its soil, or on the inability of some tenant to eke a living from this particular field. The counties of Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire were hunted by successive Earls of Berkeley up to 1801, when the pack was opened to subscription and managed by Lord Berkeley and others, the best centres for hunting being Amersham, Chesham, Missenden, Wendover, Watford and Rickmansworth. Interest in hunting and the like was not confined to the Old Berkeley Hunt however, and game keeping features prominently in the records of the 1700’s.

1762

It was required by law for the better preservation of game, that the names of game keepers be submitted to, and approved by the Clerk of the Peace. As a result we learn that in 1762 John Askell Bucknall, esquire, had been game keeper to John Hadley Lord of the Manor of Bournhall. In 1774 he was himself a Lord of the Manor – the Manor of the Moor and on 28th May appointed Gauntlet Williams, servant, to be his own game keeper, followed on August 19th 1778 by James Walker. John Bucknall was succeeded as Lord of the Manor by the Honourable William Grimston who appointed Edward Ewer on September 28th 1785, and George Harding in 1787.

These Lords of the Manor conflict entirely with the names of the owners of Manor Park during the same years. Up to 1631, the Manor of the Moor and its Park had always gone together, but in that year the 4th Earl of Pembroke who was then the proprietor, disposed of the manor. John Bucknall, it is known, farmed the manor from Moor Hall, and it seems was accordingly styled Lord of the Manor of the Moor.

1762

It was required by law for the better preservation of game, that the names of game keepers be submitted to, and approved by the Clerk of the Peace. As a result we learn that in 1762 John Askell Bucknall, esquire, had been game keeper to John Hadley Lord of the Manor of Bournhall. In 1774 he was himself a Lord of the Manor – the Manor of the Moor and on 28th May appointed Gauntlet Williams, servant, to be his own game keeper, followed on August 19th 1778 by James Walker. John Bucknall was succeeded as Lord of the Manor by the Honourable William Grimston who appointed Edward Ewer on September 28th 1785, and George Harding in 1787.

These Lords of the Manor conflict entirely with the names of the owners of Manor Park during the same years. Up to 1631, the Manor of the Moor and its Park had always gone together, but in that year the 4th Earl of Pembroke who was then the proprietor, disposed of the manor. John Bucknall, it is known, farmed the manor from Moor Hall, and it seems was accordingly styled Lord of the Manor of the Moor.

1766

On a map of C. 1766 entitled “A Survey of the Manour of Croxley and Snells Hall in the Parish of Rickmersworth and Watford in the County of Hertford belonging to Gonville and Caius College in the University of Cambridge”, we find included in the map – “Part of the Manour of the Moor”.

Among the names of “noblemen and gentlemen” who applied to the Clerk of the Peace in 1786 and received certificates for killing game were John Finch esquire, George Finch esquire, and William Sedgwick, gentleman.

The incidence of Small-pox in Croxley Green is witnessed by the survival of what was the Pest House or Small-Pox house on the banks of the Chess. This cottage, though obviously old, has a large chimney which is all that remains of a much older building. This chimney has a capacious ingle-nook, and by its narrow bricks seems to be contemporary with the old chimney of Croxley Hall.

The prevalence of the disease is demonstrated by a Sessions record of 1781 when “Sarah D------, committed for felony was ordered to remain in gaol, ‘it appearing to the Court that the prosecutor could not attend, being very ill in the small-pox’.” At the same time Small-pox was reported in the gaol itself.

Small-pox was a burden on the rates in the case of the humbler inhabitants. The Vestry records include disbursements to the afflicted poor, and payments for medicine and bleedings by apothecares.

“Harry Smiths”, the Croxley House of today, came into the possession of a family named Tuffen, descendents of the earlier mentioned Mary Tompson.

Among the names of “noblemen and gentlemen” who applied to the Clerk of the Peace in 1786 and received certificates for killing game were John Finch esquire, George Finch esquire, and William Sedgwick, gentleman.

The incidence of Small-pox in Croxley Green is witnessed by the survival of what was the Pest House or Small-Pox house on the banks of the Chess. This cottage, though obviously old, has a large chimney which is all that remains of a much older building. This chimney has a capacious ingle-nook, and by its narrow bricks seems to be contemporary with the old chimney of Croxley Hall.

The prevalence of the disease is demonstrated by a Sessions record of 1781 when “Sarah D------, committed for felony was ordered to remain in gaol, ‘it appearing to the Court that the prosecutor could not attend, being very ill in the small-pox’.” At the same time Small-pox was reported in the gaol itself.

Small-pox was a burden on the rates in the case of the humbler inhabitants. The Vestry records include disbursements to the afflicted poor, and payments for medicine and bleedings by apothecares.

“Harry Smiths”, the Croxley House of today, came into the possession of a family named Tuffen, descendents of the earlier mentioned Mary Tompson.

1737 / 1767 / 1770 / 1794

The last of these, Richard Tuffen, conveyed “Harry Smiths” in 1737 to one Solomon Andronin of Watford, who sold it in 1767 to Thomas Lord Hyde, afterwards Earl of Clarendon.It was he who built much of the present house in 1770, which was sold again in 1794 by his son Thomas, the second Earl of Clarendon to Humphry Cornwall Woolrych. The house was re-named Croxley House, greatly enlarged, becoming the residence of William Richard Woolrych, the last of the Croxley line, (Well still there, wooden wellhead machinery.)

1792

In 1792 the building of the Grand Junction Canal began. It linked the Oxford Canal from the Warwickshire border, passing by Northampton, Leighton Buzzard, and Berkhamstead, through the Grove and Cassiobury Park, across Croxley Moor and on to Uxbridge and Brentford. Here it entered the Thames, and barges could then proceed via the Paddington Canal to Limehouse. Ninety miles long, with ninety-eight locks, the Canal was opened in 1805 and the scope for Croxley’s gravel and agricultural industries began to assume national instead of local significance. An inventory of the barges on the canal in 1802 shows amongst other cargoes, hay straw, lime, dung and gravel, all of particular interest to Croxley. Only one barge appears to have been owned locally – by Mr. B------ of Cashiobirie. The inventory is not sparing in its detail. “The Thomas”, it says, “is in a foul leaky condition, and is now engaged in the Coal and Dung trade to and from the Thames and Berkhamstead; she was obliged to be pumped during the loading and unloading. Her length is 71 feet 4” and Breadth across the midships 13 feet 7 inches; she draws 13.7 inches water when light, and 48.66 inches when laden with 74 tons. She had on board, when these gages were taken, one Fire Stove, one Pump, one Anchor, one Cable, two Sets, one Hitcher, a pair of Oars, three Poles, nineteen Gratings, one Towing line and one Sternfast”.

The greatest use of the Canal in Croxley was however yet to come, and one is tempted to wonder how different our parish might have been had not the facility of water traffic been present when John Dickinson was looking around for a site for his new mill.

The “Parrotts Farm” manor of Croxley had been held since 1656 by three successive Daniel Pairetts, the last of whom bequeathed it to his son-in-law Jeremiah Smith, husband of his daughter Anne. Jeremiah said the property in 1798 to Lord Clarendon, who held it for one year only, for in 1799 it was bought by Humphry Cornwell Woolrych. He was succeeded in 1816 by his only son Humphry William Woolrych serjeant-at-law, from whom in 1871 it was inherited by William Richard Woolrych. His great aunt Miss Mary Bentley had built “The Grove” at the Green end of Balwins Lane in 1834.

The greatest use of the Canal in Croxley was however yet to come, and one is tempted to wonder how different our parish might have been had not the facility of water traffic been present when John Dickinson was looking around for a site for his new mill.

The “Parrotts Farm” manor of Croxley had been held since 1656 by three successive Daniel Pairetts, the last of whom bequeathed it to his son-in-law Jeremiah Smith, husband of his daughter Anne. Jeremiah said the property in 1798 to Lord Clarendon, who held it for one year only, for in 1799 it was bought by Humphry Cornwell Woolrych. He was succeeded in 1816 by his only son Humphry William Woolrych serjeant-at-law, from whom in 1871 it was inherited by William Richard Woolrych. His great aunt Miss Mary Bentley had built “The Grove” at the Green end of Balwins Lane in 1834.

1803

A militia for the County of Hertfordshire was first raised in 1757, and in 1803 Volunteers were formed in view of the threat of invasion by Bonaparte. That Croxley played its part in volunteers and in the greatly increased taxation is obvious, but tradition also says that the Tithe Barn housed French prisoners following the Battle of Waterloo. Yet while Wellington and Napoleon were fighting their respective ways across the world, we learn that John Finch of Redheath was awarded the Silver Medal of the Society of Arts and Commerce for the 123 fine stocks of bees he possessed in 1812.

1819

In 1819 a “Society of Good Fellowship” was established at the “Artichoke”, the rules and regulations of which were approved by the Midsummer Sessions of the Liberty of St. Albans. Societies such as these were the beginnings of Craft Unions or Friendly Societies, culminating in the Parliamentary Act of 1896 which consolidated all the previous laws regarding them. Unfortunately the Midsummer Sessions of 1819 did not see fit to preserve a copy of the actual Artichoke “rules and regulations” but it is safe to assume that they were true to type of the many similar Societies formed at Inns of that period. Subscriptions according to age varied from 1/- per month at 18 to 1/9 monthly at 45. Benefits for general sickness were 6/- per week for specified periods, while a member who became blind, lame or otherwise incapable was superannuated at the same figure. Further to sickness benefit it was allowed that “Any free member of this Society that is in Prison for Debt shall from the time he gives Notice to the Clerk of such his imprisonment be allowed 2/6 per week during the continuance thereof”. No benefits were payable following inoculation for Small-pox or through incapacity as a result of fighting! There were many regulations for upholding the dignity of such societies. A fine of 10/- was imposed on those members in receipt of benefit who frequented gaming-houses or who became “intoxicated with liquor” and “any member who shall be convicted of Felony, Theft, Swindling or Breach of Trust in any of his Majesty’s Courts of Judicators, or by Turning King’s Evidence shall prove himself Guilty of any of the aforesaid Crimes or misdemeanours he shall be excluded”. “If any member curse or swear he shall forfeit 2d. for every such offence”.

Feasts were generally held on Boxing Day and Whit Monday, the accumulated fines augmenting the funds to defray expenses. The society’s monies would be kept in a chest on the premises, there being four keys, held by the President and three stewards.

What the Registrar of Friendly Societies might have eventually thought of such rules and regulations is interesting speculation, but there is no further evidence in the Sessions records to suggest that the Artichoke Society of Good Fellowship survived long enough for his attention.

Feasts were generally held on Boxing Day and Whit Monday, the accumulated fines augmenting the funds to defray expenses. The society’s monies would be kept in a chest on the premises, there being four keys, held by the President and three stewards.

What the Registrar of Friendly Societies might have eventually thought of such rules and regulations is interesting speculation, but there is no further evidence in the Sessions records to suggest that the Artichoke Society of Good Fellowship survived long enough for his attention.

1823

But Good Fellowship was not the general rule, apparently, for a dispute is recorded in the Epiphany Sessions of 1823. An order was recited with the object of “stopping up Chandlers Lane or Rouse Barn Lane” as being “useless and unnecessary.” …. “between two old enclosures belonging to the Earl of Clarendon, continuing thence between certain coppices or woods of John Finch and the Earl of Essex, continuing its course and passing by Rouse Farm between the enclosure of Robert Williams, Esquire, and the poles of Cashiobury Park, and proceeding thence over the canal bridge ---- Free passage is reserved to the said Earl of Essex, John Finch and Robert Williams and the Masters and fellow of Caius College, and their respective tenants and undertenants, for persons, horses, cattle and carriages through the land and soil of the said highway to and from the land respectively belonging to them accordingly to ancient usage”. This “ancient usage” is evidenced by the probability that the name comes from one Henry Rowce, who was party to a deed concerning a messuage in Watford in 1527. Preservation of the lane can be accredited to Peter Clutterbuck, esquire, who successfully complained to the justice, contending that “the said highway called Chandlers Lane or Rouse Barn Lane is not unnecessary and useless”.

Thus our present ROUSE barn Lane, so often pronounced ROSE-barn Lane, probably came from ROWCE-barn and in 1766 was spelt ROWS-barn Lane !

The history of English papermaking and much of the history of Hertfordshire is synonymous. Mills for the making of pulp and paper were scattered throughout the country from the 15th Century. Locally we had Austins Mill at Mill End, McFarlanes Scot’s Bridge Mill (now the M.G.M. Offices) and Curtis’ Mill at Sarratt. There were “family affairs”, small, pulp or hand made paper mills, with only a handful of workers, mostly resident on the premises. At Loudwater, however, a Mill was purchased in 1848 by Mr. Herbert Ingram, and developed into a large business of its day. He was the founder and proprietor of the Illustrated London News, and built Glen Chess alongside his Mill, which was purchased 10 years later by William McMurray. Paper was taken to London once a week from this Mill by traction engine, and stories are still told of the noisy adventures of this method of transport in these quiet days.

Thus our present ROUSE barn Lane, so often pronounced ROSE-barn Lane, probably came from ROWCE-barn and in 1766 was spelt ROWS-barn Lane !

The history of English papermaking and much of the history of Hertfordshire is synonymous. Mills for the making of pulp and paper were scattered throughout the country from the 15th Century. Locally we had Austins Mill at Mill End, McFarlanes Scot’s Bridge Mill (now the M.G.M. Offices) and Curtis’ Mill at Sarratt. There were “family affairs”, small, pulp or hand made paper mills, with only a handful of workers, mostly resident on the premises. At Loudwater, however, a Mill was purchased in 1848 by Mr. Herbert Ingram, and developed into a large business of its day. He was the founder and proprietor of the Illustrated London News, and built Glen Chess alongside his Mill, which was purchased 10 years later by William McMurray. Paper was taken to London once a week from this Mill by traction engine, and stories are still told of the noisy adventures of this method of transport in these quiet days.

1830

But the fact that Croxley has a commercial significance all over the world must be largely credited to John Dickinson who built a paper mill here in 1830. Paper had been hand made for three centuries until the inventive genius of the Fourdrinier Brothers and John Dickinson introduced the modern era of machine made paper. Among his earlier claims to distinction had been the invention of a non-smouldering cannon cartridge paper. Primitive explosions of cartridges had proved highly dangerous prior to the invention, and the new paper was used extensively in the Peninsula War and Waterloo campaign. Paper for the Mulready envelopes now much prized by stamp collectors and the fore-runner of postage stamps was also made by Dickinsons.

To acquire this site of the Croxley mill a private Act of Parliament was necessary, and in spite of great difficulties and opposition, Royal Assent was given on June 19th 1828. The mill started working in 1830, and in the biography of Dr. A.B. Evans (Time and Chance by Joan Evans) we read “On the 10th August, drove over with the Grovers to a party of 76 whom John Dickinson entertained at dinner in the Salle of his paper Mill at Croxley to celebrate its inauguration, met all his Longman and Spottiswoode friends, and thoroughly enjoyed himself”.

8 years later this Mill was producing 14 tons of paper a week. In 1886 a great expansion took place, eliminating amongst other smaller branches, “Batcher” – the Batchworth rag mill.

Further extension in 1888 enabled all papermaking to be transferred to Croxley from Apsley and Home Park Mills, and Two Waters, Frogmore and Manchester Mills were closed.

The development of the Mill was far from smooth. Complaints from local residents about the dense smoke and “Bleach” fumes almost reached the stage of legal action. The Burning of Nitrogenous refuse, the fumes from chemical processes and the smell of boiling alfa grass were all a source of constant agitation until such problems were solved by the Mill chemists.

The Thames Conservancy board kept a constant eye on all waters connected with the mill that might eventually enter the Thames, and problems arising from possible pollution were always present.

Not the least objection to the Mills was that it would be a blot on the landscape, so that John Dickinson gave it what F.J.T. Heckford describes as a “grand Egyptian west front”. This massive pillared entrance was possibly intended, as a contemporary of Mr. Heckford has said “to soothe the Ebury’s” in neighbouring Moor Park.

It was in the Mill’s expansion years that the area around New Road began to develop. New Road, which followed what had been little more than a path between the Red House and the Artichoke is mostly of this period, the eldest house being what was “Emmas Cottage” (now Sanders Butcher’s shop) of 1872. Dickinson Square and Dickinson Avenue, built to house employees, were to follow; and occupied the old Milestone field.

A pen-picture of the Green at this time is contained in the Jubilee Number of All Saints Parish Magazine in an article “Our Little Village” under the nom-de-plume “One of the Villagers”. The writer quotes both from memory, and from a book published many years previously by another anonymous lady writer “Silsby Green”. The composite picture is of “thatched-roofed cottages nestling amongst the cherry-trees laden with blossom, and the children playing on the grass. According to tradition, (says the article). one of these cottages was used as a conventicle in bygone days, and under the floor of it is, or was, a Baptistery. Cherry Fair was an actual fair held on Cherry Sunday each year (now happily subsided, says our writer of 1922, into an invasion each summer by parties of visitors who apparently derive much pleasure from camping on the grass and solemnly eating cherries).

To acquire this site of the Croxley mill a private Act of Parliament was necessary, and in spite of great difficulties and opposition, Royal Assent was given on June 19th 1828. The mill started working in 1830, and in the biography of Dr. A.B. Evans (Time and Chance by Joan Evans) we read “On the 10th August, drove over with the Grovers to a party of 76 whom John Dickinson entertained at dinner in the Salle of his paper Mill at Croxley to celebrate its inauguration, met all his Longman and Spottiswoode friends, and thoroughly enjoyed himself”.

8 years later this Mill was producing 14 tons of paper a week. In 1886 a great expansion took place, eliminating amongst other smaller branches, “Batcher” – the Batchworth rag mill.

Further extension in 1888 enabled all papermaking to be transferred to Croxley from Apsley and Home Park Mills, and Two Waters, Frogmore and Manchester Mills were closed.

The development of the Mill was far from smooth. Complaints from local residents about the dense smoke and “Bleach” fumes almost reached the stage of legal action. The Burning of Nitrogenous refuse, the fumes from chemical processes and the smell of boiling alfa grass were all a source of constant agitation until such problems were solved by the Mill chemists.

The Thames Conservancy board kept a constant eye on all waters connected with the mill that might eventually enter the Thames, and problems arising from possible pollution were always present.

Not the least objection to the Mills was that it would be a blot on the landscape, so that John Dickinson gave it what F.J.T. Heckford describes as a “grand Egyptian west front”. This massive pillared entrance was possibly intended, as a contemporary of Mr. Heckford has said “to soothe the Ebury’s” in neighbouring Moor Park.

It was in the Mill’s expansion years that the area around New Road began to develop. New Road, which followed what had been little more than a path between the Red House and the Artichoke is mostly of this period, the eldest house being what was “Emmas Cottage” (now Sanders Butcher’s shop) of 1872. Dickinson Square and Dickinson Avenue, built to house employees, were to follow; and occupied the old Milestone field.

A pen-picture of the Green at this time is contained in the Jubilee Number of All Saints Parish Magazine in an article “Our Little Village” under the nom-de-plume “One of the Villagers”. The writer quotes both from memory, and from a book published many years previously by another anonymous lady writer “Silsby Green”. The composite picture is of “thatched-roofed cottages nestling amongst the cherry-trees laden with blossom, and the children playing on the grass. According to tradition, (says the article). one of these cottages was used as a conventicle in bygone days, and under the floor of it is, or was, a Baptistery. Cherry Fair was an actual fair held on Cherry Sunday each year (now happily subsided, says our writer of 1922, into an invasion each summer by parties of visitors who apparently derive much pleasure from camping on the grass and solemnly eating cherries).

1837

Where now stand large houses on the west side of the green were at this time open fields and farm cottages. Where Copthorne Road now joins the Green was Stone’s farmhouse, with a Smithy alongside, which would have been seen on the suspicious (if legendary) occasion of the ride of Queen Victoria along the Green shortly after her accession. Of New Road “one of the villagers” says – “It is difficult to realise that it was once possible to see the “Red House” from the gardens of the houses at the other end of the road. The houses in New Road were few and far between and fields stretched away from the “Garden Road” (now Yorke Road) to the Junction of Old and New Roads”.

1840

CROXLEY GREEN - After 1840 The several ways in which Croxley has been spelt over the centuries has been mentioned, and it may be said that nothing has done more to stabilise the spelling of place names than the introduction of the railways and the postal services. Although limited facilities for “posting” have existed for some hundreds of years, it was with the rapid growth of the railways that the present “post office” era was born. Nevertheless the post office “got in first” at Croxley, and should take the credit of finally designating the village “Croxley Green”. Prior to the opening of the “Crown” post office in Watford Road in 1949, the office had been in various places, the earliest possibly being at the cottage “South View” at the New Road corner of the Green. Here, may be seen a bricked-in pillar box “mouth” in the Green-side wall. The garden protruding further along on the green is said to have housed the village pound of the same period. A further survival of Croxley’s early postal facility is the UR. box at Sears Farm. The postman’s beat of those early years was from Rickmansworth to Chipperfield, which he walked ! Needless to say, there was only one delivery a day. Travel in the first half of the 19th century was by foot, horse, sedan chair, post-chaise or stage-coach. A Sarsen stone reminiscent of a mounting block is visible outside All Saints church hall, and has remained near enough to its old position since cottages were demolished prior to the building of the church hall.

A new bell now hangs on the original metal fixture on the eaves of the “Coach and Horses”, and a tug on the rope attached to the original bell would have summoned the landlord to attend to weary travellers in far off days. Doubtless the high placing of the bell, whilst still enabling the drivers of vehicles to reach the rope, happily avoided the giving of false alarms by Croxley urchins.

Gentlemen of the parish wore pigtails at this time and were dressed in fancy coats, knee-breeches and black silk stockings with silver buckled shoes. Williams records that the “red cloak with hood” was much worn by the wives and daughters of labouring men, with “wooden pattens shod with iron rings, to be followed by wooden clogs with leather toe-caps and heels”.